You have been lied to about plastic recycling : where the plastic in our oceans really comes from.

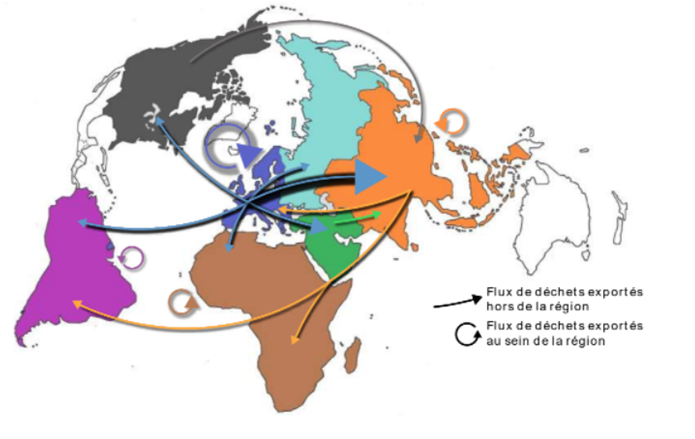

Picture taken from the report ‘Pollution Plastique : une bombe à retardement ?’, presented to the French Sénat and the Assemblée Nationale in the name of the ‘Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques’ in December 2020

What do you believe happens when you put your recyclable waste into a green bin?

I always believed that when I discarded my shampoo bottle, it went to a waste sorting unit where workers sort the materials by types – plastic, cardboard, metal, etc. My bottle was then sent to the nearest facilities that could recycle it. Following this worthwhile effort, and some chemical restoration, my former shampoo bottle was ready to be put back into circulation and be used to manufacture new products. There may have been some waste here and there, some parts that could not be recycled because of contamination or improper household waste sorting – a phenomenon commonly known as ‘wish-cycling’ – that ended up in local landfills. But all things considered, the plastic waste that did qualify for recycling (including my shampoo bottle) would find its route back into the market.

And the plastic that floats around in the Pacific Ocean, that infamous plastic that strangulates poor turtles on the other side of the planet? My ‘recycled’ shampoo bottle cannot be there, right?

Indeed, the common narrative is that this ocean pollution is generated by South-East Asian countries, either because they do not realise the harmfulness of plastic pollution – a typically paternalistic western talking point – or because they do not have the means to put in place the costly infrastructures to recycle the high volumes of plastic they produce. This last bit is unfortunately true; according to the report ‘Plastic Waste: a ticking time bomb?’, presented to the French government in December 2020, and which I will use as the main reference for this article, the greater part of plastic pollution is produced by very few countries, specifically South-East Asian and Pacific countries. This is mitigated, however, by the fact that most of the plastic production takes place in this region: 51% of the world’s plastic was produced in Asia in 2018. That’s 183 million tons of plastic, of which 108 million was manufactured in China: this is equivalent to over 900,000 plastic blue whales being released into the world every year!

Regarding pollution, up to 25% of marine plastic contamination stems from leaks within the waste management of South-East Asia and Pacific countries, while the remaining 75% are caused by insufficient local waste collection programs. Obviously, this observation leaves out why plastic production – and subsequent waste – occurs mainly in this area of the world, and the salient responsibility of Western countries in the massive production of plastic waste there – but this is not what I want to discuss today.

What I will highlight, however, is a disturbing paradox we face: on the one hand, the World Bank estimates that the volume of waste in the South-Eastern Asian/Pacific region will have doubled in size by 2050. On the other hand, the French report’s assessment of the current situation is that it is “unrealistic to believe that setting up a waste management system alone will be enough to end the problem of plastic pollution”. Indeed, to do so would require hooking up more than a million households per week to a waste management unit for 20 years – and that is for our current rate of plastic production, not the 2050 rate! Basically, this report declares that no amount of human intervention can mitigate the monstrous amount of plastic pollution that is being produced today, nor tomorrow, nor in 2050, considering the rate of current and future production. Macroplastics, the name given to plastic waste bigger than 5 mms (about 0.2 in), will keep accumulating in the oceans, on beaches, everywhere. Micro and nanoplastics, the effects of which are still unclear – although some studies have flagged up alarming effects on ecological systems and human health – will increasingly contaminate our food, soil and habitats.

Usually, at this point in the reading of an alarmist article like mine, I remember all the boats that come to collect some of the waste making up the ‘seventh continent of plastic’ in the Pacific Ocean. I find comfort in the beach cleanings that are organised all around the world, including here in Scotland where I am writing this article: at least some of us are willing to bring relief to the overflowing plastic waste management system in Asia and take it upon ourselves to recycle it. And most importantly, I believe that when I put my plastic waste into a green bin, I do not add to this seventh continent. However comforting this line of thinking may be for me, though, I must now address the biggest lie we have been told in The West…

In 2016, the United Kingdom exported more than 300,000 tons of plastic waste to China. France exported just over 400,000, and the US 800,000 12% of ‘Chinese’ plastic waste was actually imported from the rest of the world, the biggest culprits being Japan, the US, Germany, Belgium, France and the UK. China initially benefited from plastic waste importation, as it was used to fuel its booming resin industry. However, by 2017, China possessed the necessary infrastructure to manufacture plastic from scratch and banned the importation of non-industrial plastic waste. The result? We sent the waste to other South-East Asian countries instead – the very same countries which lack the infrastructure needed to manage their own plastic waste production.

This is a sad truth: we keep picturing the countries in the Southern Hemisphere as the ‘bad guys’ of recycling and waste management, all while getting ourselves off the hook by sending our waste – which is truly gargantuan when examined per capita – for them to process. This makes us look better – like magic, all the waste we send away to the other side of the planet vanishes from our records, while it cleverly tarnishes the reputation of the global south. On our pedestal, we rue their inability to handle all that trash – while we are the ones who effectively trash them.

By ‘we’, I mean you, me, everyone who recycles and does not recycle. Indeed, the report points out that the higher the recycling rate in our Western country is, the higher the chance of our waste ending up in the oceans. Plastic waste exportation itself causes pollution: 5% of exported plastic waste leaks into the environment. For the UK alone, that represents 15,000 tons of plastic per year that end up in our ecosystem – 75 blue whales!

Before concluding this article, I want to add a caveat. The report does emphasise that waste exportation is not unilateral – Asian countries do export some waste to Western countries, and they import plastic waste from other Southern hemispheric countries. Unfortunately, there is a lot of grey area surrounding this phenomenon – the flux of waste is hard to quantify as there is little data on it, surprising perhaps when you consider the large multinational industries built around this trade. What is certain, however, is that as long as this trade keeps happening, plastic will keep poisoning our oceans, harming our health and the ecosystem – even the ones we so thoughtfully ditch in the green bin.

Obviously, I am not telling people to go all out and completely quit sorting out their waste – as it does significantly improve the chance of it being recycled. But the takeaway from this is that it is not enough – and that we must stop blaming foreign countries for their lack of action and take responsibility for our inaction. Not only must we build more efficient recycling plants, but we must also reduce plastic production. Half of the plastics being made annually are for packaging purposes – packaging our food, our shampoo, and for Amazon deliveries. Policies are slow to be implemented and rarely are they enough: if we want to protect turtles and penguins from premature death, we must become more responsible with our use – and not assume that the green bin is a magic hat that makes pollution disappear.

Joséphine BOURRINET

Bibliography :

All information and data are taken from the report ‘POLLUTION PLASTIQUE :UNE BOMBE À RETARDEMENT ?’ Presented by M. Philippe BOLO, deputy, and Mme Angèle PRÉVILLE, senator on December 10, 2020.

No Comment