Vietnam’s defence strategy in the Indo-pacific

By Apolline BURNICHON

At the heart of the Indo-Pacific, Vietnam has developed a defence strategy focused on safeguarding its sovereignty against complex security challenges and a growing regional competition. Tensions over maritime claims in the East Sea and China’s rising power ambitions drive Vietnam to strengthen its military capabilities by modernising its armed forces and building a strategic network of bilateral and multilateral partnerships.

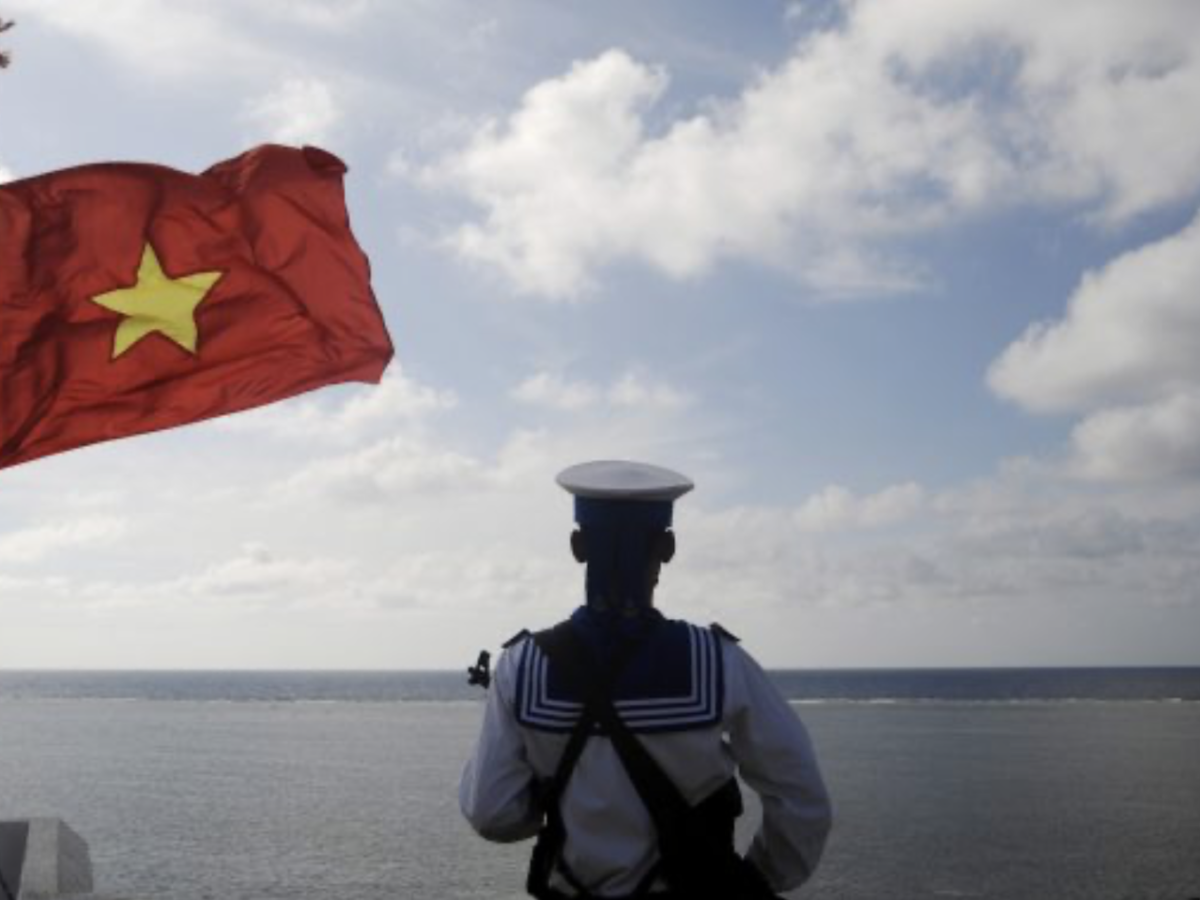

Photo : Quang Le / Reuters

Since 2008, Vietnam’s military spending has more than doubled from $2.14 billion to $5.5 billion in 20181. This increase can be explained by numerous factors, including the intensification of territorial rivalries, particularly over maritime and island territories, the modernisation of its armed forces, but also the development of an increasingly diverse range of security threats and its participation in various security alliances.

Vietnam occupies a leading position in Southeast Asia, with the highest gross domestic product in the region. It is also the country with the most « privileged » relations with the major players in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, the country maintains a special relationship not only with China, due to a geographical proximity, but also with India and the United States, with which Vietnam has historical ties. What’s more, Vietnam’s location at the crossroads of several Asian countries and its vast coastline make it particularly vulnerable to foreign incursions.

Delimitations of the Indo-Pacific area according to several national strategic documents, Géoconfluences

The Indo-Pacific region, a vast area whose boundaries vary depending on one country’s point of view, has been the subject of major disputes in recent years. It also brings together countries whose regional and global importance has grown steadily in recent decades, making them major powers. The Indo-Pacific can be defined as a region encompassing both the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, but the trend is to define the Indo-Pacific mainly around the two most powerful countries in the area: China and India. The Indo-Pacific region is also the battleground of several ideological struggles, one of which is the Sino-American rivalry and another is the place that China should occupy in the region: should China’s opening up in the Indo-Pacific be encouraged or, on the contrary, should it be opposed?

It is because of all these security issues related to the Indo-Pacific region that Vietnam is adopting a clear defence strategy. Indeed, Vietnam’s significant economic growth in recent years has enabled it to integrate further into the region, particularly through trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). In addition, the country’s proximity to both China and the United States makes its situation complex and delicate. As a result, Vietnam is developing its own independent strategy, of which the Four No’s policy is the centrepiece.

The Indo-Pacific region is at the centre of development dynamics and occupies an increasingly important place in geo-economic, geopolitical, and geo-strategic terms. Vietnam had to develop both an active and passive defence strategy in order to ensure that it is considered at its true value in the Indo-Pacific and to defend its interests as effectively as possible. Thus, Vietnam is developing and modernising its military capabilities to secure its own security and national sovereignty. At the same time, it is building alliances in the Indo-Pacific region to enhance its deterrence.

Vietnam’s strategy is based on a set of clearly defined objectives, the cornerstone of which being maintaining regional stability. In addition to developing its military capabilities and its network of alliances with key players in the Indo-Pacific, Vietnam is encouraging regional cooperation initiatives, particularly within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). By promoting initiatives at the regional level, Vietnam may hope that it will be able to position itself as a leading player in the sub-region to reduce China’s overinfluence. In this regard, Vietnam has implemented an “omnidirectional military diplomacy”2 that aims to build alliances using the bilateral scale, especially with influential countries in the Indo-Pacific region such as the United States, Japan, India, and the multilateral frameworks of the ASEAN for security cooperation. In parallel with this diplomacy, Vietnam bases its entire defence policy on the so-called “Four No’s”.

It is therefore worth taking a closer look at the various levels of defence policy that Vietnam implements to respond to all the security challenges it faces.

The Four No’s policy or Vietnam’s claim of peaceful dispute settlement

As a nonaligned country, Vietnam has long based its defence policy around the objective of defending the independence and sovereignty of its homeland and maintaining international peace. With this in mind, in its National Defence Book of 2009, Vietnam expressed for the first time its will to stay away from international or regional military strategies and partnerships, by implementing the Three No’s policy3, i.e:

- No military alliances with other countries ;

- No siding with one country against another ;

- No foreign military bases or use of Vietnamese territory to oppose other countries.

Since 2009, this three-no policy has been the backbone of Vietnam’s military diplomacy. This policy was designed to reassure China about Vietnam’s potential rapprochement with the United States. The policy guaranteed China that Vietnam would not form any military alliance with its American rival, and that the United States would not be able to establish military bases on Vietnamese territory4.

Ten years later, in its 2019 National Defence Book, Vietnam has expanded its Three No’s policy to Four No’s in order to comply with its principle of settling “all disputes and divergences through peaceful means on the basis of international law”5. This expanded policy guides Vietnam’s national defence strategy by adding the principle of no “using force or threatening to use force in international relations”6 to the three basic principles of the 2009 policy.

However, this policy does not prevent Vietnam from establishing, or maintaining, cooperative defence relations. In fact, Vietnam continues to cooperate with other countries and even “promotes defence cooperation with countries to improve its capabilities to protect the country and address common security challenges”7.

Nevertheless, Vietnam does not rule out developing “military relations with other countries” if the circumstances require8. In any case, Vietnam aims to become a valuable player on the world defence scene, and this means developing its military capabilities.

The need to develop and modernise Vietnam’s military capabilities

Vietnam is a strategic gateway to the Asian continent, as it lies on the vital sea lines of communication between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and is a gateway to the Strait of Malacca. In addition, its 2,000 miles of coastline in the South China Sea make it even more of a key, but also vulnerable, location in the region. Indeed, the disputes over maritime sovereignty in the South China Sea have made it all the more important to strengthen and modernise Vietnam’s military capabilities in order to counter the Chinese « northern giant ».

Throughout its history, Vietnam has fought against several countries, such as China and the United States, whose presence in the Indo-Pacific is no longer in question. In this context, Vietnam has developed a defence policy based on independence, autonomy, and peace. In addition, Vietnam, like the rest of the world, is experiencing a diversification of security threats to its national sovereignty (terrorism, climate change, food shortages, disinformation, cyber-attacks, arms trafficking, etc.), forcing it to adapt its defence strategies. The 2019 White Paper, which outlines the national defence policy, states that its main goal is to “safeguard the homeland” and to “maintain a peaceful environment for a socialist-oriented national construction”9.

The need to develop and modernise Vietnam’s military capabilities is closely linked to these objectives and to the army’s close relationship with the Party. Indeed, the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) and its leaders are doing everything possible to ensure that their defence strategy is built around the Party and the socialist ideology that guides it.

Thus, the modernisation and development of Vietnam’s military capabilities will be to the advantage of the Party, which is committed to protecting the homeland and working for its own stability and influence.

- The relationship between the Vietnam Communist Party (VCP) and the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA)

To better understand Vietnam’s defence strategy in the Indo-Pacific, it is important to explain the relationship between the VCP and the VPA at the domestic level.

Over the past 30 years, we have witnessed an “institutionalisation”10 of the VCP’s control over the Vietnamese armed forces. Indeed, the VCP has increasingly used the army for political purposes, and this evolution can be seen by simply analysing the evolution of the Vietnamese constitutions since 1992. Although the 1980 Constitution did not explicitly state that the PCV would dominate the army, Article 45 of the 1992 Constitution changed this relationship, stating that: “all units of the people’s armed forces must show absolute loyalty to the motherland and the people; their duty is to stand ready to fight to safeguard national independence and sovereignty, the country’s unity and territorial integrity, national security and social order, to safeguard the socialist regime and the fruits of the revolution, and to join the entire people in national construction”11. This commitment has been reaffirmed in Art. 65 of the 2013 Constitution, which states that, “the people’s armed forces must show absolute loyalty to […] the Party, […]; their duty is […] to protect the People, the Party, the State, and the socialist regime and the fruits of the revolution, and to join the entire people in national construction and fulfilment of international duties.”12.

With each successive constitution, the VCP has strengthened its grip and control over the VPA, which therefore plays an important role in the defence and stability of the current regime. The army’s dominant role in maintaining the regime is also reflected in the creation of Task Force 47 in 2017. This new military cyber unit, which is part of the VPA, aims not only to control internet use but also to combat false views and criticism of the Party found on the Vietnamese internet.

It is also interesting to note that this devotion of the army to the party is also presented as one of the objectives of Vietnam’s defence strategy in the 2019 National Defence Book, which states: “The VPA has been undergoing reforms […] truly meeting its mandate as an army of the people, a political force, a loyal and reliable fighting force of the VCP, State and people, and the determinant of Homeland protection in the new situation”13. This sentence describes the army as both a political and a fighting force that aims to protect the VCP and its prosperity and popularity among the Vietnamese people. The 2019 National Defence also describes the VPA as a “revolutionary”14 force, giving it a stronger political overtone.

The army is thus closely linked to the party, which holds all the senior military positions. In fact, the highest military body in Vietnam is the Central Military Commission of the VCP, which is composed of members of the Politburo (the highest body in the VCP that sets the broad outlines of the government policy) and military leaders15, and is headed by Nguyễn Phú Trọng, the General Secretary of the VCP. This information is therefore key to understanding the relationship between the VCP and the VPA, but also to better understanding the defence policy being implemented in Vietnam.

- An overview of Vietnam’s military capabilities

The military capabilities of a country can be understood as “the ability to achieve a desired effect in a specific operating environment”16. The greater a country’s military capability, the more protected its position on the international stage will be, as it will be able to defend itself against a potential aggressor. A strong military capability also acts as a powerful deterrent, deterring other countries from attacking. A country’s military capabilities can be of different types (material, human…) and can have different levels of technology. As for Vietnam’s military capabilities, they are both material and personal.

Most of Vietnam’s military equipment dates back to the Cold War, and originates from the Soviet Union. In fact, since the end of the Second World War, Vietnam had been buying its military equipment mainly from the USSR. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Soviet giant’s preponderance in terms of arms supplies became even more pronounced. Since then, no American warplanes have flown into Vietnam, largely because the Communist Party, which came to power in the same year, naturally turned to another communist regime (the USSR) for arms supplies. In addition, the arms embargo imposed by the United States on the Vietnamese regime at the end of the Vietnam War (1975) did not encourage the diversification of arms imports into Vietnam. Thus, despite the lifting of the US embargo on May 23rd, 2016 and the diversification of Vietnam’s arms partnerships (notably with France, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Israel), Russia remains the main weapons supplier to the Vietnamese. However, since the lifting of the embargo, the United States has sought to reduce Vietnam’s dependence on Russia, notably through the introduction of financing facilities17.

Nevertheless, Vietnam seeks to reduce its dependence on foreign countries, particularly from Russia and the US by diversifying its weapons suppliers. In this regard, the country expanded its cooperation with Japan concerning defense equipment transfers18. At the moment, however, Vietnam does not have all the industrial capacity needed to build its own military aircraft or ships and is therefore considering continuing to buy weapons from Russia or the United States. It is also interesting to note that, a few days after Joe Biden’s visit to Hanoi, on September 9th, 2023, discussions have begun between the United States and Vietnam on concluding an agreement on a new partnership between the two countries, including a major arms deal. This discussion follows an article in the New York Times alleging that Vietnam was secretly trying to buy Russian weapons.

In order to reduce its dependence on foreign powers, Vietnam is increasingly investing in the defence sector to develop further advanced technologies and enhance its military capabilities. As the country stated in its 2019 Defense White Paper, “Vietnam is determined to develop its defence industry”19. Indeed, Vietnam’s budget (in nominal terms) has increased significantly over the past 10 years. This budget increase can be explained by Vietnam’s desire to develop its own defence industry in the face of new and increasingly diversified security challenges. Although Vietnam produces armoured vehicles and light weapons domestically, and seeks to develop high-tech systems such as radar and anti-ship missiles in conjunction with foreign partners, its production capacity remains limited. To this end, Vietnam is drafting a Law on Defence Industry, Security and Industrial Mobilisation20, which aims to strengthen the defence industry sector and make it a spearhead of national industry.

In addition to its material resources, Vietnam built its military capabilities around the “All-people Force”21. All citizens aged between 18 and 27 are required to do a military service so that they can be mobilised when needed. Vietnam’s human military capacity can be divided into three categories: permanent forces, temporary forces, and people’s forces, which play a role in all sectors of the Vietnamese economy (industry, agriculture, etc.). Vietnam is also able to mobilise young people thanks to the education they receive at school, which is decided by the Party and unites the Vietnamese people around their nation and the need to protect it. In addition, Vietnam can count on the support of three categories of armed forces in charge of building this “all-people national defence”22 strategy : the Main Force, the Local Force, and the Militia and Self-Defence Force23. Each of these categories has a different and complementary field of action :

- The first is an elite force capable of acting quickly in large-scale operations,

- The second has the characteristics to respond to missions in a specific local defence zone (province, district…),

- The last one is a mass self-defence force, which will have to lead the war waged by the entire population and carry out civil defence missions.

By mobilising as many Vietnamese as possible in its armed forces at various levels, Vietnam is optimising its national defence potential, defined as “the human, material, financial and spiritual resources that can be mobilised both at home and abroad to accomplish national defence missions”24.

However, given its size, Vietnam is not in a position to defend itself alone against the major powers in the Indo-Pacific region. The country will therefore multiply its network of security cooperation in order to ensure its full and complete protection throughout the region, while maintaining its desire to preserve its territorial integrity. The first level of cooperation for Vietnam is the regional level, and more specifically the ASEAN, an organisation within which the socialist country is able to engage in dialogue with all the countries in Southeast Asia. For Vietnam, this organisation represents a real and concrete alternative to China.

An increasing number of partnerships at different levels

- The ASEAN, a key forum for cooperation between Vietnam and the countries of Southeast Asia

As the third military budget of the ASEAN, Vietnam is one of the leading countries of the organisation.Vietnam joined the ASEAN in 1995, at a time when the country was seeking security in the Southeast Asian region. Vietnam’s integration into the ASEAN group has been a driving force for the country, boosting its credibility outside the region and helping it to emerge from the isolation it has suffered since the late 1970s. Since then, Vietnam has worked jointly with other ASEAN member states to maintain and secure regional peace and reconciliation. This goal now extends beyond ASEAN to the entire Indo-Pacific region.

The importance and dynamism of Vietnam within the organisation was particularly evident in 2006, when Vietnam proposed the establishment of the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM)25. The ADMM brings together all the armed forces ministers of the ASEAN member states and aims to draw up guidelines for each member state to implement in the field of defence. In this way, it has helped to gather the defence ministers of the various countries in the region, and to ensure that ASEAN member states work together to adopt a coherent policy across the region, giving them greater credibility on a wider scale. With this initiative, Vietnam has become one of the leading countries within the ASEAN in maintaining peace and stability, acting as a bridge between “second-level” and “first-level”26 Southeast Asian countries in recent years. Indeed, tensions in the East Sea27 have forced it to assert itself within the regional organisation to ensure its own security, as well as that of its neighbours. It is therefore necessary for these countries to adopt a coherent policy and strategy in order to safeguard their interests vis-à-vis China. Thus, after almost two decades of meetings, this framework has established numerous cooperation mechanisms among ASEAN countries in the fields of counter-terrorism, cyber-security, maritime security, and the defence industry.

In addition, to further consolidate ASEAN defence relations, the Vietnamese Minister of Defence frequently hosts his counterparts from the region and establishes bilateral defence policy dialogues in order to consolidate and deepen Vietnam’s bilateral defence ties, which would enable the country to maintain “a peaceful environment for national development”28. In this regard, Vietnam aims to expand its cooperation, especially in Southeast Asia, as evidenced by the opening of the 1st Vietnam-Thailand Bilateral Defence Policy Dialogue on December 13th, 2023. In addition, since the end of 2023, the General Phan Van Giang, the Vietnamese Minister of Defence, has held defence dialogues with his counterparts from Thailand (January 10th, 2024)29, but also from Laos (October 22nd, 2024)30, and China (August 20th, 2024)31. The General also met the Defence Minister of Malaysia (December 5th, 2023)32, Cambodia (November 13th, 2023)33, and Indonesia (October 31st, 2023)34. Finally, Vietnam’s will to consolidate the peace and the stability in the region can also be seen in the 1st Vietnam-Laos-Cambodia Border Defense Friendship Exchange35, which was held in December 2023 and which established an annual meeting between the Defence Ministers of the three countries.

All these initiatives clearly demonstrate Vietnam’s commitment to a “regional rules-based order”36. Nevertheless, Vietnam cannot ignore the issues surrounding the Indo-Pacific, which is a new area of tension where the country must juggle with the major powers that oppose it.

- Extra-regional cooperation, or the « diversification of international relations »

Since its declaration of independence in 1945, Vietnam has pursued a policy of “diversification of international relations”37, which can be defined as “a way for a newly independent country to navigate the post-war environment”38. Indeed, Ho Chi Minh declared at the time that he wanted “to be friends with every democratic nation […] despite the Cold War division”39. This desire was reiterated on several occasions, most notably at the end of the Cold War in 1991, when Vietnam’s representatives declared that they wanted to be on good terms with “everyone in the international community” who sought peace and stability40. As a result, Vietnam has gradually expanded its alliance options and is willing to expand defence relations and cooperation regardless of differences in political regimes and levels of development.

Over the years, Vietnam has sought to expand its influence in the international community by promoting diversification and multilateralism in international relations. After being a simple participant that played by the rules, Vietnam is now a full-fledged player in the forums that govern international life, proposing and promoting its own rules within these institutions. As a matter of fact, Vietnam has set up defence and security relations with more than 80 countries41. In 2021, it had 14 “strategic partners” 42, among which eight (China, Russia, India, South Korea, Japan, Australia, the United States and France) have already been promoted as “comprehensive strategic partners” in 2024. France is the latest country, and the first from the EU, to establish a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Vietnam on October 7th, 2024. Moreover, same as at the regional level, the Vietnamese Minister of Defence is stepping up meetings with his foreign counterparts. In a few months, the General Phan Van Giang has received the defence ministers of Japan (August 6th, 2024)43, New Zealand (March 4th, 2024)44, the Republic of Korea (April 24th, 2024)45, France (May 5th, 2024)46, and the United States (September 9th, 2024)47. These countries have a significant influence in the Indo-Pacific region, thanks to their military capabilities and to the ultra-marine areas that form part of their territory, which allow them to project significant hard and soft power in the region. This does not mean, however, that Vietnam has forged strong and close alliances with all the countries in the international community, quite the contrary. In fact, most of Vietnam’s allies are located in an area that could be described as the wider Indo-Pacific, which includes the countries mentioned above. Three countries stand out from the rest of the international community: the United States, China and India. It is therefore relevant to explain in more detail the particular defence relationships between these countries and Vietnam.

United States-Vietnam’s “special” relationship

Bilateral dialogue between the US Secretary of Defense, Lloyd J. Austin III, and the Vietnamese Defence Minister General Phan Van Giang, in Washington DC., On September 9th, 2024, (US. Department of Defense)

Since the end of the Vietnam War, the two countries have had an ambivalent relationship. The war was a major defeat for the United States, and Vietnam moved much closer to the USSR afterwards. However, after the fall of the USSR and the end of the Cold War, relations between Vietnam and the United States improved, and Vietnam is now considered as “one of the United States’ leading regional partners”48 in the US Indo-Pacific strategy.

The main reason for this rapprochement between the two countries is the confrontation between China and the United States. The two countries have been locked in an ideological struggle for several decades, and Vietnam is under constant threat from China, which last invaded the country in 1979. China’s hegemonic ambitions as it builds its New Silk Road have prompted Vietnam to seek an ally to counterbalance China’s power if necessary. Moreover, territorial claims in the South China Sea mean that Vietnam needs to strengthen its defence ties in the wake of China’s worrying behaviour. In this regard, Vietnam sees the United States as a natural defender and maritime security partner in the East Sea.

Although Vietnam has long viewed the United States as a potential threat to its regime, military and defence ties between the two countries have strengthened in recent years. In 2018, for example, Vietnam participated for the first time in RIMPAC, the world’s largest biennial maritime military exercise overseen by the United States. Vietnam’s participation represents a real step forward in Vietnamese-American military cooperation. This US-Vietnam rapprochement can also be seen in the evolution of the vocabulary used by the US to describe Vietnam. In its 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, the US giant described Vietnam as one of the three “key players in ASEAN”49, alongside Malaysia and the Philippines, with whom it needed to strengthen its relationship. In 2022, the White House identified Vietnam as one of the « leading regional partners » alongside countries such as India, New Zealand and Singapore50. Vietnam is also one of the seven countries to receive US assistance and training to improve maritime security51.

Moreover, the “mutual trust”52 between Vietnam and the United States is reflected in the signing of a Comprehensive Partnership in 2013, which was upgraded to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (the highest level of diplomatic cooperation) ten years later, in September 2023. Furthermore, Vietnam’s growing importance on the international stage is due in no small part to the United States, with the most recent historic summit between the United States and North Korea taking place in Hanoi in February 2019.

However, this rapprochement with the United States must not come at the expense of China, which could react negatively. Indeed, China wields considerable influence in Vietnam, not only because of their geographical and historical proximity, but also because of China’s dominance in the Vietnamese economy.

The complex relationship between China and Vietnam

Bilateral meeting between the Vietnamese Defence Minister, General Phan Van Giang, and the Chinese Minister of National Defence, Senior Lieutenant General Dong Jun, on August 20th, 2024 (Ministry of National Defence of the SRV)

The Sino-Vietnamese relationship can be characterised as one of dependency, and sometimes subservience. In fact, the similarities between their political ideals and systems would make them good allies. However, the relations between China and Vietnam are complexified by a painful past for Vietnam, which has been invaded by its northern neighbour on several occasions. The territorial disputes in the East Sea, where China claims almost all the maritime zones, also plays a major role in the tensions between China and Vietnam as the Chinese claims conflict with the Vietnamese’s. Moreover, given the geographical proximity of the two countries (806 miles of land border separate them), it is not in Vietnam’s interest to directly confront the northern giant, as the country remembers the 1979 invasion and does not want to see it repeated. In this context, Vietnam wants to maintain “a stable relationship with China”53, and avoid “actions that could be interpreted as aligning against it”54. Each and every one of its actions is therefore taken seriously so as not to upset its complex relationship with China.

In light of what has been said, Vietnam cannot move too close to the United States out of fear of alarming China, which is closely monitoring the rapprochement between its southern neighbour and its main global rival, seeing it as a threat. China is therefore seeking to strengthen its influence in Vietnam, as demonstrated by Xi Jinping’s visit to Hanoi in December 2023, just a few weeks after Joe Biden’s visit in September and the Vietnamese president’s visit to the United States in November on the occasion of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting. In addition, the visit to China on October 28th by General Phan Van Giang provided an opportunity for the two countries to discuss the need to step up the organisation of friendly exchanges in the field of border security and to strengthen defence cooperation (personnel training, industry, etc.).

Vietnam and China are high-level partners in security and defence, and the “Vietnam-China Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership”55 signed in 2008, is expected to be strengthened in 2024 with the visits of the Secretary of the Central Committee of the VCP (Lê Hoài Trung) in March, and the President of the Vietnamese National Assembly, Vuong Dinh Huê, in April.

Thus, despite its rapprochement with the USA and its asymmetrical relationship with China, Vietnam’s policy remains largely influenced by its geographical proximity to and economic dependence on China. Therefore, China stays a major partner for Vietnam, even though it still poses a potential threat and desires to control Vietnam, as is shown by the alleged Chinese cyber attacks against Vietnam to strengthen its regional influence.

India: the new pawn on the chessboard

The Vietnamese and Indian delegates at the 3rd Vietnam-India Security Dialogue, on December 5th, 2024 (Ministry of public security of the SRV)

India’s importance to Vietnam’s defence strategy in the Indo-Pacific is relatively recent. In fact, the actual establishment of Indo-Vietnamese defence and security relations dates back to 1994, when the Protocol on Defence Cooperation Agreement was signed. This rapprochement between the two countries can be explained in particular by India’s introduction of the Look-East Policy in 1992 (which became the Act-East Policy in 2014), aimed at strengthening India’s relations with the countries of the Southeast Asian region. Under this policy, India aims to become an alternative to China for these countries. In addition, in 2000, the Indian Defence Minister emphasised the importance of building a strong relationship with Vietnam regarding the disputes that were occurring in the South China Sea. Since then, the two countries have continued to forge closer ties, notably by strengthening their cooperation in various areas of security and defence through the establishment of various negotiating structures such as the Vietnam-India Strategic Defence Dialogue and the ASEAN-India Summit. These close ties are reflected in the implementation of a « strategic partnership » between the two countries in 2007, which was upgraded to a « comprehensive strategic partnership » in September 201656, making India one of Vietnam’s main strategic partners. Since then, the two countries have taken steps to promote their defence ties. Indeed, in 2014, Vietnam and India signed a $100 million credit agreement for Vietnam to purchase Indian defence equipment, including high-speed patrol boats that were handed over to Vietnam in 202257. In the same year, India released a new $500 million Defence Line of Credit for Vietnam, enabling the country to strengthen its defence capabilities58.

Further, India is also doing all it can to protect Vietnam from China’s worrying behaviour. For example, in 2021, the Indian Navy established a task force in the South China Sea and the Western Pacific Ocean for two months. As India is China’s main rival in the region, Vietnam expects it to be one of its closest allies. Moreover, since 2016, India and Vietnam have been organising a biannual security dialogue to solidify their cooperation in the scope of their comprehensive strategic partnership. The 3rd India-Vietnam Security Dialogue was held in Hanoi on December 5th, 2024 and enabled the two countries to strengthen their cooperation in counter-terrorism and enhance their collaboration in cyber-crime59.

All of India’s positive actions on Vietnam’s behalf have therefore been fruitful, as Vietnam expects India to become an important “security supplier”60 and “balancing force”61 in the security of the Indo-Pacific region.

By Apolline Burnichon

Endnotes :

- World Bank data, Military expenditure (current USD) – Viet Nam, (available online) ↩︎

- Tomotaka Shoji, Vietnam’s Omnidirectional Military Diplomacy: Focusing on the South China Sea. Originally published in Japanese in Boei Kenkyusho Kiyo, vol.18, no.1, November 2015 ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Viet Nam National Defence, November 2009, pp. 21-22 (available online) ↩︎

- Thayer, Carlyle A, “US-Vietnam Relations: Post Mortem – 5,” Thayer Consultancy Background Brief, September 13th, 2023 ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National defence book, 2019, p.23 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National defence book, 2019, pp23-24 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National defence book, 2019, p.24 (available online) ↩︎

- “Depending on circumstances and specific conditions, Vietnam will consider developing necessary, appropriate defence and military relations with other countries”, Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National defence book, 2019, p.24 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p.21 (available online) ↩︎

- Bich T. Tran, Evolution of the Communist Party of Vietnam’s Control Over the Military, The Diplomat, August 29th, 2020 (available online) ↩︎

- The Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1992), Article 45 (available online) ↩︎

- The Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2013), Article 65 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, Foreword, p.5 ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p.13 ↩︎

- Bich T. Tran, Evolution of the Communist Party of Vietnam’s Control Over the Military, The Diplomat, August 29th, 2020 (available online) ↩︎

- Hinge, Alan, Australian Defence Preparedness: Principles, Problems and Prospects : Introducing Repertoire of Missions (ROMINS) a Practical Path to Australian Defence Preparedness, Australian Defence Studies Centre, Canberra, 2000, p.15 ↩︎

- Lagneau Laurent, « Le Vietnam pourrait se procurer des chasseurs-bombardiers F-16 auprès des États-Unis », Opex 360, September 23rd, 2023 (available online). ↩︎

- Kim Felix, “Hanoi, Tokyo deepen cooperation with new defense agreements, equipment transfers”, IndoPacific Defense Forum, August 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defense of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p. 39 (available online) ↩︎

- Lê Tuyêt, « Le Vietnam élabore un projet de loi promouvant les industries de défense et de sécurité, ainsi que le soutien à l’industrie », VOV International, February 21st, 2024 ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defense of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p. 45 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defense of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p. 5 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defense of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defence, 2019, p. 47 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defense of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National Defense, 2019, p.35 (available online) ↩︎

- ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting, About the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting, January 11th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Manh, L, D, K (2022). Vietnam’s Perception and Response to the Emerging Indo-Pacific Regional Security Architecture. Ilomata International Journal of Social Science, 3(1), p.42 (available online) ↩︎

- Name given to the South China Sea by Vietnam ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, “Vietnam’s international integration and defence diplomacy work reviewed”, April 2022 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, Senior Lieutenant General Hoang Xuan Chien receives Commander-in-Chief of Royal Thai Navy, February 23rd, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, Vietnam, Talks held between Vietnamese and Lao defence ministers, October 23rd, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “General Phan Van Giang meets his Chinese counterpart”, August 21st, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, Malaysian Defence Minister pays an official visit to Vietnam, December 12th, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “Vietnam, Cambodia promote defence relations”, November 14th, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “Vietnam, Indonesia hold this defence policy dialogue”, November 1st, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “The first Vietnam – Laos – Cambodia Border Defense Friendship Exchange officially held”, December 15th, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- Trinh Viet Dung, and Do Huy Hai, «“Vietnam balances between Indo-Pacific powers”, East Asia Forum, February 23rd, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Do Hoang, Policy of diversification helps Vietnam build ties with the Indo-Pacific, United States Institute of Peace (USIP), November 20th, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- The Cove, “#KYR: Vietnam – Military”, October 20th, 2021 (available online) ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “Vietnam, Minister Phan Van Giang hosts a welcome ceremony for Japan’s Defense Minister”, August 7th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “Vietnam, New Zealand hold defence policy dialogue”, March 12th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence relations, “General Phan Van Giang receives Deputy Defence Minister of the Republic of Korea”, April 25th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “General Phan Van Giang receives French Defence Minister”, May 6th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ministry of National defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Defence Relations, “General Phan Van Giang holds talks with U.S. Defence Secretary”, September 11th, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Bich Tran, U.S.-Vietnam Cooperation under Biden’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), March 2nd, 2022 (available online) ↩︎

- The United States Department of Defense, “Inco-Pacific Strategy Report : preparedness, partnerships, and promoting a networked region”, June 1st, 2019, p.36 ↩︎

- The White House, “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States”, February 2022, p.9 ↩︎

- Defence security cooperation agency, Section 1263 Indo-Pacific maritime security initiative (MSI), 2016 (available online ) ↩︎

- President Vo Van Thuong’s speech at the US Council on Foreign Relations, Nov. 2023 ↩︎

- Trinh Viet Dung, and Do Huy Hai, “Vietnam balances between Indo-Pacific powers”, East Asia Forum, February 23rd, 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

- Le courrier du Vietnam, « Le Vietnam et la Chine approfondissent leur coopération en matière de défense », October 29th, 2023 (available online) ↩︎

- The Indian Embassy in Hanoi, India-Vietnam relations, December 2024 (available online) ↩︎

- Peri Dinakar, “Rajnath Singh hands over 12 high-speed guard boats to Vietnam”, The Hindu, June 2022 (available online) ↩︎

- Jha, P. K., India, Vietnam in the Indo-Pacific: A Unifying Construct. CLAWS Journal, 15(1), 2022, p.48 ↩︎

- The Indian Embassy in Hanoi, 3rd India-Viet Nam Security Dialogue (available online). ↩︎

- Manh, L, D, K (2022). Vietnam’s Perception and Response to the Emerging Indo-Pacific Regional Security Architecture. Ilomata International Journal of Social Science, 3(1), 2022, p.44 (available online) ↩︎

- Ibidem ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY :

Bich, T., Evolution of the Communist Party of Vietnam’s Control Over the Military, The Diplomat, August 29th, 2020

Bich, T., U.S.-Vietnam Cooperation under Biden’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), March 2nd, 2022

Do, H., Policy of diversification helps Vietnam build ties with the Indo-Pacific, United States Institute of Peace (USIP), November 20th, 2023

Goin, V., “The Indopacific Space, a Geopolitical Concept with Varying Geometry in a Field of Competing Powers”, Géoconfluences, October 2021. Translated from French by Charlotte Musselwhite-Schweitzer in March 2024

Hinge, A., Australian Defence Preparedness: Principles, Problems and Prospects : Introducing Repertoire of Missions (ROMINS) a Practical Path to Australian Defence Preparedness, Australian Defence Studies Centre, Canberra, 2000

Jha, P. K., India, Vietnam in the Indo-Pacific: A Unifying Construct. CLAWS Journal, 15(1), 2022, pp.38-55

Kim, F., “Hanoi, Tokyo deepen cooperation with new defense agreements, equipment transfers”, IndoPacific Defense Forum, August 2024

Lagneau, L., « Le Vietnam pourrait se procurer des chasseurs-bombardiers F-16 auprès des États-Unis », Opex 360, September 23rd, 2023

Lê, T., « Le Vietnam élabore un projet de loi promouvant les industries de défense et de sécurité, ainsi que le soutien à l’industrie », VOV International, February 21st, 2024

Manh, L, D, K (2022). Vietnam’s Perception and Response to the Emerging Indo-Pacific Regional Security Architecture. Ilomata International Journal of Social Science, 3(1), pp.38-50

Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Viet Nam National Defence, November 2009

Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, 2019 Viet Nam National defence book, 2019

Peri, D., “Rajnath Singh hands over 12 high-speed guard boats to Vietnam”, The Hindu, June 2022.

President Vo Van Thuong’s speech at the US Council on Foreign Relations, November 2023

Thayer, C. A, “US-Vietnam Relations: Post Mortem – 5,” Thayer Consultancy Background Brief, September 13th, 2023.

The Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam of 1992

The Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam of 2013

The United States Department of Defense, “Indo-Pacific Strategy Report : preparedness, partnerships, and promoting a networked region”, June 1st, 2019

The White House, “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States”, February 2022

Shoji, T., Vietnam’s Omnidirectional Military Diplomacy: Focusing on the South China Sea. Originally published in Japanese in Boei Kenkyusho Kiyo, vol.18, no.1, November 2015.

Trinh, V. D., and Do, H. H., “Vietnam balances between Indo-Pacific powers”, East Asia Forum, February 23rd, 2024

SITOGRAPHY :

- ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (available online)

- Defense security cooperation agency (available online)

- Le courrier du Vietnam (available online)

- The Cove (available online)

- The Ministry of National Defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (available online)

- The Indian Embassy in Hanoi (available online)

- World Bank data (available online)

P.S. Le Vietnam n’a pas le plus gros PIB de la région.