Hosting embassies at Louis XIV’s & Qianlong’s courts: two rulers, one guest ritual?

By Juliette WU-VIGNOLO

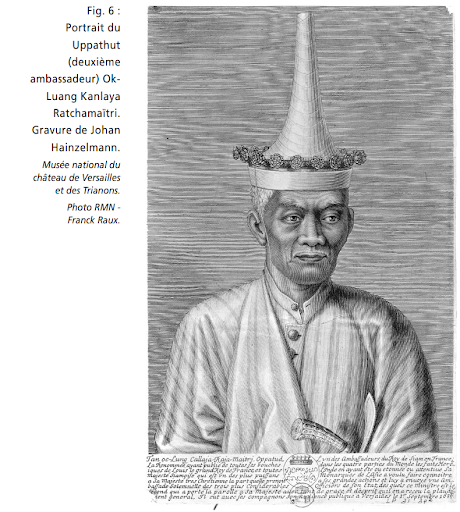

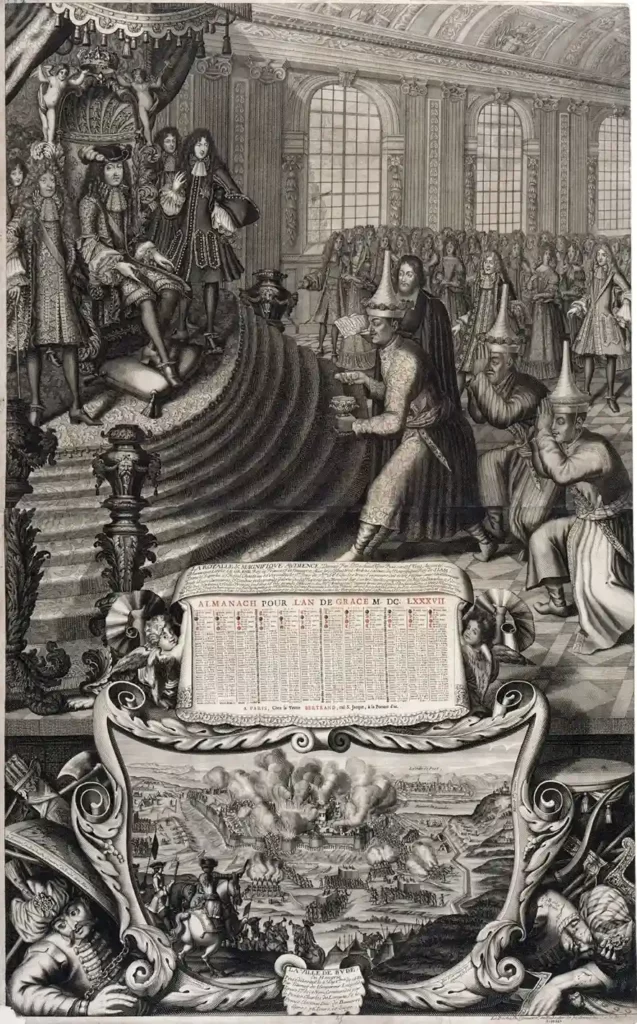

“Sunday, September 1, 1686 at Versailles: The king gave audience to the ambassadors of Siam, on a throne which one raised to him at the end of the gallery which touched the apartment of Madam the Dauphine. The order was very beautiful, and Her Majesty said that M. d’Aumont, first gentleman of the chamber in the year, should be praised for it. The ambassadors spoke very well; the Abbé de Lyonne, the missionary, served as their interpreter; they remained at the foot of the throne until they presented their master’s letter to the king; they went up to the last step to give it to him. Nobody at the audience was covered but the king, who took off his hat only once or twice. The Siamese showed a very deep respect by all their faces, and returned to the end of the gallery, always backwards, not wanting to turn their backs to the king; they are three ambassadors, they have four gentlemen and two secretaries, and eat all nine together; the remainder of their suite is only valetage. The second ambassador had been ambassador to China, and the King of Siam sent him to compare the French court with that of China, which he believed to be the two most beautiful courts in the world.”

From the Marquis de Dangeau’s journal, 1st volume1.

A comparative study between guest rituals in France and China during the 17th and 18th century (1686, 1715, 1793)

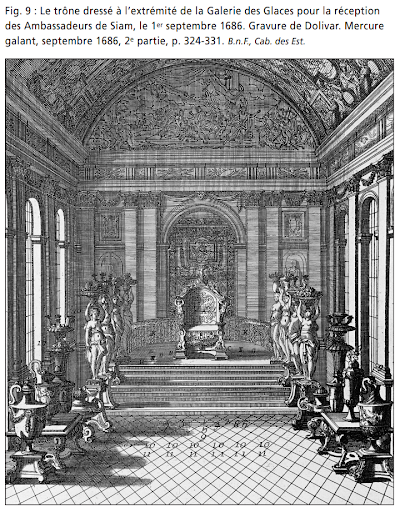

On September 1st, 1686, three ambassadors from the king of Siam, Phra Narai, were granted an audience by Louis XIV at the Galerie des Glaces, Versailles. Being received at the Galerie des Glaces is an honor that is said to only have been bestowed thrice in the thirty-three years the French king spent at the palace, each instance an exceptional event. On February 19th 1715, Mehemet Reza Beg, ambassador of the Persian shah Hussein Mirza, was welcomed in turn in the Galerie. Both embassies were sent in order to establish military alliances and trading partnership with Louis XIV. However, it appears that their motives played close to no part in the reason why the embassies received such preferential treatment in their reception. This rather had to do with the fact that they came from distant nations, Siam and Persia respectively, places the European mind could only vaguely fathom and fantasize about at the time. As Voltaire would later describe them in his Age of Louis XIV, the embassies were perceived as “tributes coming from so far away without being expected”2, and were widely celebrated as such. This wording is reminiscent in many aspects of the Chinese maxim 怀柔遠人 (huáiróu yuǎn rén: “cherishing men from afar”), which had a significant weight in Chinese diplomatic practices. As a result, distance was also the reason why the Qianlong emperor accepted a British embassy on Chinese soil in 1793. Lord Macartney, who was tasked by King George III to establish amicable relations with the emperor in order to facilitate trade, was granted an audience at Rehe on September 1st, 1793. Rehe was a summer hunting-retreat established in 1703 by Qianlong’s father, the Kangxi emperor, just like Versailles itself was originally one of Louis XIII’s hunting-retreats, later erected as a palace by his son, Louis XIV.

Singularly, the similarities between Hongli (the other name of the Qianlong emperor) and Louis XIV do not stop there. In fact, through the careful study of the three embassies mentioned above – Siam, Persia, and Great-Britain – we will see that the diplomatic guest rituals practiced at the Qing court and at Versailles are actually quite comparable. A guest ritual can be comprehended as a set of practices and customs related to the reception of foreign embassies at court, practices reflecting the political ambition and representation of a sovereign’s moral and social order. Although the reigns of Qianlong (1735-1796) and Louis XIV (1643-1715) took place almost a century apart, a certain number of common points can be found between the two monarchs. That is not to say, of course, that their guest rituals are absolutely identical, for that statement would not be true. Rather, after bearing witness to an extensive amount of work comparing Louis XIV to the Kangxi emperor, the objective would be to posit the analogy between Qianlong’s and Louis XIV’s guest rituals as a viable alternative to the first one. To achieve that, we will build on the seminal work produced by James L. Hevia (Cherishing Men from Afar, 1995), and Greg M. Thomas (“Yuanming Yuan / Versailles : Intercultural Interactions between Chinese and European Palace Cultures”, 2009).

By contemplating Louis XIV’s and Qianlong’s guest rituals in a similar light, we will demonstrate that the two rulers shared a common understanding of the guest ritual’s purpose, as translated in the similarity of the practices observed. The examination of diplomatic gifts, its role and its reception by the hosting country, likewise displays a closer alignment in guest ritual practices and diplomatic traditions, in both courts. The commonality can even be applied to the very essence of the three embassies’ perception by the hosting country, which, borrowing James L. Hevia’s conceptualization, can be described as an “encounter between two imperial formations”3.

Coinciding practices in guest rituals and shared understanding of political purposes

Hongli and Louis XIV both viewed guest ritual as a way to establish social order, respect, obedience and stability in their realm. For the Qing emperor, “guest ritual provided the context in which the lesser lord’s strength was both acknowledged (that is, differentiated from that of other lords) and shown now to be part of a whole”4. Such a process built and maintained social hierarchy within the Qing empire. For the French king, guest ritual was “an effective instrument of power that exhibited, on a broad and highly ritualized stage, his authority and prestige, thus both conserving and securing his rule”5. In his Mémoires pour l’Instruction du Dauphin written in 1665, Louis XIV clearly enunciates the importance of such protocol. It was necessary, he states, to elevate the monarch “so far above all others that no one else may be confused or compared with him… [because French] subjects usually judge by appearances, and it is most often on amenities and on ranks that they base their respect and obedience.”6 Guest ritual thus participated in the reaffirmation of social rank at court, through the visual display of power prepared for foreign visitors. As analyzed by N. Elias in his works7, Louis XIV’s reign was truly formative in the extension of court practices to the whole of society. Therefore, by ordaining court through a set of highly-ritualized protocols like the King’s daily routine or more exceptional events, such as the reception of foreign embassies at Versailles, Louis XIV consecutively brought into order the entirety of French society.

Through these proceedings, Qianlong and Louis XIV furthermore chose to present themselves as the center of a cosmological order that they were meant to embody, literally. The kingly or imperial body was elevated and became a source of worship8. Both sovereigns are depicted as descending from and personifying the will of a higher power. By transcending mortal laws, they consequently hierarchize the rest of society. To better distinguish themselves, they adopt various titles which aim at legitimizing their claims. Qianlong was “the Chinese Son of Heaven”9, successor of imperial dynasties, and “incarnate bodhisattva Manjusri”10, while Louis XIV was “Dieu-donné” (God-given)11, but also “le Roi-Soleil” (Sun-King), and sometimes perceived as a divinity himself. Certainly, gods and bodhisattvas are not perfect equivalents, but the religious power and imagery these figures hold remain the same, just like their undeniable influence on ritual practices at court. Said influence can be read in the significance granted to the body language in diplomatic proceedings, and more especially in the positions held by each participant of the guest rituals12. Following the instructions given in the Comprehensive Rites of the Great Qing, here is what we can surmise from positioning during Chinese guest rituals:

“The emperor was located at the north end and on the centerline of an audience hall, facing south toward the world of human affairs. In this capacity he was the supreme lord, the lord of lords, the generative principle, and those before him, his servants, were the completing principle. […] Other participants were ranked and located on his left and right hands from north to south. The left side of the hall was where civil officials were placed, while the right side was reserved for military officials and members of the eight banners.”13

Following this careful recounting, Qianlong must have been positioned at the center of the audience hall, stating his supremacy, while the rest of his court is spread around him, occupying the rest of the space. By conferring symbolic significance to the position of each participant, the Qing guest ritual links the spiritual world to the physical world, connecting the two with the objective of restoring cosmological balance and reproducing social order.

At Versailles, the king usually received ambassadors in his private chambers. Alice Camus gives a thorough description of the bodies’ placement:

“In his room, the king is covered and seated in an armchair that has been placed in the alley of his bed [in French, “la ruelle” the space between the bed and the wall, intimate and sacralized]. The princes of the royal house, the princes of blood and the legitimated princes who are present surround the king. They are standing and uncovered. The king is also accompanied by the great officers of the Household of the king, namely the great chamberlain, the first gentlemen of the chamber, the great master of the wardrobe and the masters of the wardrobe. All are placed behind the king’s chair.”14

Just like Hongli, Louis XIV is placed at the center of this configuration. Further regulations also went as far as assigning each and everyone a definite position during the escort leading the embassy to its audience. Such a well-adjusted and synchronized procedure aims to demonstrate the king’s power on the body of his subjects who, now compliant to these minute protocols, perform as many well-oiled cogs in the machinery of French monarchy. For the Siam embassy audience event at the Galerie des Glaces, the French periodical Le Mercure Galant had published a precise plan of each participant’s position in the audience room, showing once again the importance in the arrangement of the subjects’ bodies15.

Aside from body positions during guest rituals, the cosmological order manifested by Hongli and Louis XIV was also expressed in the configuration of their respective palaces and gardens, where foreign visitors were often taken for a walk. From Macartney’s journal, we know that he was shown the Yuanming Yuan Gardens more than once. It is there that European curiosities were exposed during Qianlong’s reign. On October 2nd, 1793, for example, Macartney had a meeting in these gardens where he tried to broach business topics with the imperial ministers Heshen, Fukang’an and Fuchang’an. From the Marquis de Dangeau’s journal, we know from an entry written on Wednesday October 2nd, 1686, that “the king saw the ambassadors of Siam a lot […] in his gardens, where he forbade that no one entered while they were walking there, so that they could see everything with more comfort and freedom”16. As reported by Greg M. Thomas, “art systems functioned within palace space to enact royal power and prestige”17.

Royal palaces and royal gardens complete a double-function, both performative and authoritative. The royal palace enforces the wealth, power and influence of the sovereign. It is supposed to hint at (or in some cases, blatantly demonstrate) his character. For example, by featuring a wide array of art pieces in his palace, the ruler can brandish evidence of his qualities as patron of the arts. Correspondingly, the royal gardens materialize man’s domination over nature. When the king takes a stroll in his gardens, he reminds his court (and by extension, the rest of his society) of his status as nature-tamer. He’s reappropriating control over the wilderness, with all the analogies that can be made between wilderness and human nature. Additionally from being considered separately, the palace-garden complex can also be understood as a whole, illustrating the relationship uniting the city to the countryside, and producing a miniature representation of the realm of sorts. We know that “Qianlong’s residential quarter at Yuanming Yuan included nine islands with palaces representing the ‘Nine Realms’ of the empire and evoking nine stars and the nine mountains of the Buddhist cosmos, while other sections of the grounds evoked magical realms of immortals or replicated historical gardens he had visited around China.” In France, “Versailles likewise included symbolism of eight rivers of France, along with gods, planets and seasons” and the palace itself was aligned east to west, to refer to Louis XIV’s moniker as “Sun-King”18. Moreover, as depicted in the quoted passages earlier on, wandering the royal gardens is (also and) essentially a diplomatic activity. First because, as previously said, it aims to exhibit the ruler’s power and status ; second, because it is in these moments that are most readily discussed agreements and alliances.

Next, let’s focus a bit more on the temporal sequence of the three embassies which present quite a few similarities. Before giving further details, let’s remember that China and France both draw distinctions in the type of audience granted to the ambassadors. “The Comprehensive Rites drew a distinction between Grand and Regular audiences, which were differentiated by the presence of a certain order and quantity of people and things”19, while the French court distinguished between “public audiences” (also called “ceremonial audiences”)20, which served as welcome or farewell, and were purely formal, “particular audiences” where monarch and ambassador dialogue on political matters, and “secret audiences” where similar matters were discussed but without the courtiers present (only admitting the king, the ambassador and the secretary of State for foreign affairs).

French and Chinese guest rituals both begin “with the greeting of the embassy at a periphery of the imperial dominion”21, as outlined in the Comprehensive Rites of the Great Qing. Macartney was welcomed in Tianjin, the Siamese ambassadors at Brest, and the Persian Beg in Marseille. After having their identities confirmed, the gifts were inspected and sent to the capital. Then, happened “the inspection, management, and caring for the embassy and the offerings by successive peripheral officials, who passed the embassy on to the court”. In light of the fact that all three embassies came from far-away lands, they received the privilege of being escorted and entertained on the road to the capital. This was presented as “the first of the imperial bestowals” in the Chinese guest ritual, granted to the Macartney embassy by Hongli in his imperial benevolence. It has been noted in several instances that many feasts were organized by officials for Macartney’s sake during the first month of his stay22. In France, the privilege of having all expenses paid for by the King for the entire duration of their stay was also granted to Oriental embassies. Examining the Marquis de Dangeau’s writings, we learn that Louis XIV commissioned Mr. Torf, “gentilhomme ordinaire” to this specific end in 1686. The Siamese ambassadors were shown through the Loire Valley, where they received “extraordinary honors in the villages along their route”, arrived at Vincennes on “Friday 26th of July 1686”, stayed at Berny until “Monday 12th of August 1686”. After their meeting with the king, they also toured through the region of Flandres between “Wednesday 2nd of October 1686” and “Wednesday 20th of November 1686”, and attended parties, notably in the castle of Saint-Cloud on “Tuesday 26th of November 1686”.

After the escort to the capital began the preparation for the audience of the embassy, including the sorting and presentations of the ambassador’s gifts to the rulers (the Siamese presents for example, were arranged in the Glaces Gallery starting from “Wednesday August 28, 1686”23). Only afterwards came the long-awaited audience. Required greetings performed by the ambassadors during the audience seem almost matching between France and China : at the Qing court, “after stepping back from the table, the ambassador [must] perform three kneelings, bowing his head to the ground thrice each time”24, just like in France, where the ambassador had to perform three bows before the king25. It is during this audience that is formally delivered the letter written by the ambassadors’ sovereign. Personally handed over in front of the court to the receiving monarch, the letter symbolically (re)activates the relationship between the two countries, sealing the link between guest and host.

The response letter, from host ruler to guest ruler, would be received by the ambassadors just as they were taking their leave and being escorted back to the periphery of the realm, from where they would depart again for their home countries. Once again, this formal letter-delivery would often take place during a ceremony either performed by the ruler himself or one of his officials.

Gifting and receiving diplomatic gifts

The offering and subsequent receiving of presents is a fundamental part of the guest ritual. Here, I interpret the gift as an extension of a monarch’s power in another state. I posit that the diplomatic gift fulfills two purposes : the embodiment of the embassy’s motives, and the acknowledgement of the authority and legitimacy of the rulers through the act of exposition.

Before proceeding with the reasoning, I will first provide a brief account of the gifts brought by the three embassies. Guo Fuxiang details that the presents brought by the Macartney embassy “comprised a total of more than 590 items in nineteen categories”26, which intended to “show the level of British technological advancement, reflect the aesthetics of English culture, and be potentially important trade commodities between China and Great-Britain in the future”. Among them, we found luxurious astronomical tools, arms and horse-riding equipment, fabrics, pieces of art depicting the English monarchy as well as its landscapes and cultural points of reference. “The total cost for all the presents was as high as £15,610” (roughly equivalent to 162 124 euros). The Siamese presents to the French monarch numbered silverware, decorative objects and arms equipment, porcelains and lacquers27. It is to be noted that, by some irony of history, the two silver cannons that were gifted to Louis XIV by Phra Narai during the embassy, later served to the storming of the Bastille on July 13th and 14th, 178928. Regarding the Persian presents, much more modest in quantity, they consisted in “one hundred and six small pearls, one hundred and eighty turquoise stones and two jars of Mumie’s gum”29.

Developing commerce and securing military aid were the primary mission objectives, as seen in the nature of the diplomatic gifts. Indeed, when it comes to the Macartney embassy, the presents sent to the Qianlong emperor clearly served as an “exhibition of the products of English industry”30, especially from Birmingham. Lord Macartney himself represented not only the interests of the British crown, but also that of the British East India Company. Therefore, he had prepared in advance a list of commercial propositions and adjustments to be made to the trade in Canton, duties” levying on British ships traveling between Canton and Macao, free access to Canton for British merchants as well as freedom to trade with merchants other than the ones sanctioned for the time-being, leave to learn the Chinese language and that they please distinguish them from Americans31.

In the case of Siam, the Marquis de Dangeau reports that the Siamese ambassadors were indeed sent to negotiate agreements pertaining to trade32. Phra Narai’s objective, in sending an embassy to the French court, was to “to develop trade, a source of revenue, [thanks to the presence of French] and to ensure protection against the Dutch, who were very aggressive in defending their trade in Asia”33. The Siamese king therefore requested military troops in exchange for which “he was ready to concede to the French full freedom of trade in his states and a port of their choice, and he promised the materials necessary for the construction of houses”34. France was, of course, particularly interested in this venture, seeing that trade with Siam, beyond the new market it represented, would open further perspectives for commerce in China, or in Japan (which access was solely restricted, except for the Dutch). Moreover, as the French East India Company was known to be in constant deficit, business opportunities as advantageous as this one could not be passed up. In addition to that, Meredith Martin explains that “many believed Siam to contain abundant gold and silver mines that were ripe for exploitation” as well as tin, metals “that Louis XIV’s agents wished to acquire from Siam”35. In this light, Phra Narai’s diplomatic gifts seemed particularly appropriate : offering silver cannons and gold pieces in abundance, he sustained the fantasized idea that French people had about Siam natural resources, and implicitly reiterated the objectives of his embassy to the Sun King’s court.

Equally important is the diplomatic gift’s role in acknowledging the legitimacy of both guest and host sovereigns. One particular feature of the diplomatic gift in both Chinese and French guest rituals refers to the fact that it always goes through an exhibition phase at the court of the hosting monarch. Thereupon, I argue that the act of gift exhibition, or more accurately exposition (from the latin ex-ponere, to “put forth”), can be analyzed in three ways relevant to the current study :

- The diplomatic gift is “put forth”, meaning pushed outside the boundaries of a space (here, the realm of the gifting monarch). Outside the boundaries of the territory where it was originally created, the gift subsequently brings with it the political and cultural weight of its native country’s ambitions and representations.

- The diplomatic gift is “put forth”, meaning highlighted, as in put in evidence by the monarch to whom it is gifted. This action builds the value of the diplomatic gift through the construction of a specific, almost sacralized space, where the exposed object can only be “touched with the eyes”.

- The diplomatic gift is “put forth”, exerting a power of attraction that can be described as influence, inviting people to come and see it. The sight of the audience coming en masse to see said gift builds up the legitimacy of both rulers. The legitimacy of the monarch-gifter on one hand, because he produced the exhibited object, the value of said object having been constructed in the act of exposition discussed in the previous point. The legitimacy of the monarch-receiver on the other hand, because his authority and worth is acknowledged, through the receiving act itself, by his fellow monarch. Also, because as a possessor of a high-value object, his authority is reinforced in the eyes of his subjects. The hoarding, or collection of invaluable treasures in royal palaces is known as one of the strategies put in place to better differentiate the ruler from their subjects (Versailles and Yuanming Yuan being perfect examples of that).

However, in all three embassies studied, the diplomatic gifts brought were considered disappointments. Qianlong, when addressing King George III about the presents he sent, famously declared:

“The Celestial Empire, ruling all within the four seas, simply concentrates on carrying out the affairs of Government properly, and does not value rare and precious things. […] We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need for your country’s manufactures.”36

According to some witnesses, upon seeing the gifts, Qianlong would even have said that “these things [were] only good enough to amuse children”37, but were otherwise unfit for an emperor.

The same goes for the Siamese offerings. The Abbé de Choisy recalls in his Mémoires, the despise the French Minister of War, Louvois, showed to the ambassadors’ gifts:

“The gifts they [the Siamese ambassadors] had brought were stored in the salon at the end of the gallery [Salon de la Guerre]. M. de Louvois, who didn’t think much of things in which he had no part, despised them extremely. “Mr. l’Abbé“ he said to me in passing, ”is all that you have brought there worth fifteen hundred pistols? I don’t know, sir,” I answered as loudly as I could, so that I could be heard, « but I do know that there are more than twenty thousand écus of heavy gold, not counting the manners ; and I’m not saying anything about the Japanese cabinets, the screens and the porcelain. He made, while looking at me, a disdainful smile and passed by.”38

The Dauphin as well didn’t seem to show much consideration for the gifts, only considering them as trinkets and organizing “the very next day […] a lottery of a part of the gifts he had received from Siam”39 (although this practice was also aimed “at satisfying the social obligation of princes to be ”liberal”, i.e. not to accumulate gifts for their entourage”, in order to maintain social order within Versailles’ court).

The gifts from Persia were, without a doubt, the most unappreciated of them all. In fact, they seemed so unappreciated that they were considered downright offensive by a good portion of the French court. In Saint-Simon’s own words, “the ambassador’s behavior was as disgraceful as his wretched suite and miserable presents.”40 On his part, the baron de Breteuil remarks that:

“The public was scandalized to the point of saying all the infamies of the world about the ambassador, until the majority, and even people of the first consideration, wanted to persuade themselves that it was an impostor who, not only did not come on behalf of the king of Persia, but that he had never been at his court, and that he had brought counterfeit credentials.”41

However disappointed Qianlong, Louis XIV, and their respective courts might have been by the presents brought to them, this does not remove the intrinsic function of the diplomatic gift. Indeed, as the Chinese art merchant Ching Tsai Loo recalls, gifts play the role of “silent ambassadors”, “mute diplomats”42. Bruno Latour’s theory on objects as “actants”, non-humans acting in the same way as humans, is also useful in this context: “Objects make something” says the philosopher “and first they make us.”43 To Bing Zhao and Fabien Simon, “acting thus as objects of power and courtesy, the nature [of the diplomatic gift] is ambivalent : their intrinsic characteristics (aesthetic, economic and technical) had to reflect as well the identity of the one who offered them as the one who received them”. They are, what they name “material expressions of power, of the recipient as well as of the receiver”.

Furthermore, let’s not forget that, while the Macartney embassy gifts were considered disappointing indeed, “the Qing imperial records accounts of more than a year-long process of sorting, marking, packing up, using, giving out as rewards, and finally displaying the Macartney Embassy’s presents illustrate[d] the importance that the Qing court attached to these presents, and to their appropriate handling and preservation”44. Guo Fuxiang, who studied this gift handling in-depth, argues that Hongli’s response to the British presents was caused by the fact that the empire’s “foreign interaction had always been limited to the system of tributaries paying homage to a China entrenched in an ideology according to which the emperor ruled the Celestial Empire with the Mandate of Heaven”. Hence, according to him, the cultural discrepancies between the two countries stimulated by the previous scant amount of contact between them would explain this mixed reaction.

While this could indeed be the case, this argument fails to provide a satisfying comprehensive explanation. Therefore, drawing on J. L. Hevia’s argument, we will endeavor to demonstrate that the reception of gifts and other practices composing the guest ritual are actually the representation of…

“…An encounter between two imperial formations”45

James Hevia’s initial proposition in his study is to “recast [the encounter of the Macartney embassy] as one between two expansive imperialisms, the Manchu and the British multiethnic imperial formations […] their principles of organization as discourses of power, each produced by a ruling bloc for the maintenance of its position and the reconfiguring of its social world”. He dismisses the theory of cultural misunderstanding that was prevalent in the interpretation of the Macartney embassy (and supported by historians like Guo Fuxiang, for example, as we have seen). Furthering his thought, we can call on Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s take on the concept of “cultural incommensurability”46. According to him “disparate empires [still] shared some common objectives.”47 Thus, conflicts rising during diplomatic encounters could be better apprehended if considered to “be shaped by commensurability and not necessarily marked by enmity”. In this regard, the Persian embassy of 1715 is particularly revealing. Numerous conflicts have emerged during the few months Reza Beg spent in France, and the predominant ones will be explored more in-depth later. Mokhberi affirms that: “the visit of Mohammad Reza Beg, an event that seems to embody hostility between France and the Safavid Empire, actually highlights similarity and understanding between the two monarchies.” On these grounds, it is then possible to theorize that guest rituals, for Qianlong and Louis XIV, are effectively understood as a display of power and influence for both the hosting sovereign, and the sending sovereign represented by his ambassadors.

Adherence to court protocol in guest ritual is absolutely crucial. It was already defined as such in Europe by Michel de l’Hôpital (1507-1573), as early as the 16th century. Prime minister of French king François II, he viewed court protocol as a “non-constitutional solemnity [that] contributed to the grandeur of monarchy and heightened the royal function”48. It is in this light that we can understand the struggles that arose during the Persian embassy. On one memorable occasion indeed, French and Persian troops almost came to exchange blows in 171549. The altercation follows a botched attempt, on Reza Beg’s part, to refuse to comply with French ceremonial customs, notably in regard to the expectation put on the Persian ambassador to “stand upon receiving high-ranking Frenchmen”, which he refused on account of his religion. According to S. Mokhberi, “the ambassador’s struggle to include Safavid diplomatic practices during the course of the visit signaled an effort to maintain the dignity of the Persian monarchy and its superiority to the French equivalent. […] He did understand that giving up his own diplomatic traditions in favor of a foreign system meant yielding power. In the end, both Breteuil and the Beg understood the performance of power inherent in ceremony.”50 This validates Catherine Bell’s argument on ritual practices being “themselves the very production and negotiation of power relations.”51

Similarly, in 18th century China, negotiation of power relations were also at play regarding court protocol for the audience during the Macartney embassy. The British ambassador refused to kowtow to the Qianlong emperor, and spent a major part of the days upcoming the audience bargaining with Chinese officials, in order to replace the kowtow with something else. For Hevia, Macartney’s reticence can be apprehended through the fact that “[genuflexion and kowtow] hit at the very core of British notions of sovereignty by attacking the dignity of the sovereign. To perform such acts would, therefore, preclude the possibility of mutual recognition of sovereign equality.”52

Projection of grandeur through guest ritual was the other main form of power display. In the Qing empire, reception of foreign embassies provided the opportunity for the hosting country to display its power, in a much more blatant manner. In 1793, fearing that the British had hidden motives in coming to pay homage to him, Qianlong ordonned that his troops be posted on full display on the road to Guangzhou, so that Macartney could take measure of the Qing military potential, and be subsequently dissuaded to stir up trouble.

Moreover, reinforcing the court’s reputation was at stake when receiving embassies, especially because it demonstrated the attractive capacity of a nation. In the tributary system of the Qing empire, “tribute presented by foreign rulers performed the useful function of garnering to the court the prestige it needed to remain in power. In other words, the submission of other princes to the emperor functioned to legitimize the ruling house”53.

Versailles, on the other hand, was described as “a beacon in the Europe of courts and remained the absolute reference as long as the curial civilization lasted in Europe, that is to say until the beginning of the 20th century.”54 Louis XIV’s court was mythified, influential “to the point of becoming a paradigm against which other [courts] had to take sides.” Versailles was also represented as a “political laboratory” that young European aristocrats visited in their great tour of Europe, in order to instruct themselves.

Display of power during diplomatic visits also meant circulating images and texts on the reception and performance of guest rituals, be it in the form of “medals”55, or prints as was the case during the Siamese embassy56.

Finally, while discussing the negotiation of power dynamics in diplomatic visits, it is essential to call upon the Chinese concept of a “centering path”. The latter is presented as a key-element to asserting dominance in the Qing guest ritual, both a principle guiding the behavior of the emperor and a quality of character he must endeavor to achieve as much as possible. In his dealings with the British embassy, Qianlong described it as following:

“In dealing with matters concerning outsiders (waiyi), you must find the middle course between extravagance and meagerness (fengjian shizhong), so that you correctly accord with Our imperial order (tizhi). The provinces have the inappropriate habit of either exceeding or falling short [of the middle course]. In this case, after the British ambassador arrives, treatment of him cannot be overly grand. But the ambassador has sailed far to visit Us for the first time ; this cannot be compared to Burma, Annam, or others who have come for many years to present gifts. [We] must judiciously care for them and avoid too mean a reception, because that would make these distant travellers take us lightly (qing).”57

The concept of “centering path” didn’t explicitly exist in Europe. However, if we define centering path as a way of finding a middle ground between two opposites, we can envision Louis XIV’s reception of Oriental embassies as a derivative form of it. Instead of finding “the middle course between extravagance and meagerness”, the Sun King finds the middle ground between Oriental and French customs. Ronald S. Love proved that “Louis XIV and his protocol officers copied as nearly as possible the outward forms of Siamese court ceremonial”58. In 1686,

“the French King received the Siamese ambassadors on a silver throne, situated on a high platform covered with a floral carpet, mimicking the lofty throne of the Siamese monarch Phra Narai and the floral pattern of his reception hall in Siam and donned a diamond-encrusted outfit. During the Siamese embassy, an observer described how the entry of the three diplomats through the rooms of Versailles was accompanied by “the sound of trumpets and drums, imitating the custom of the King of Siam, who never descended to an audience hall without this music.”59

In the same way, in 1715, “Louis XIV commanded his courtiers to dress magnificently to compete with the finery of the Safavid court. He ordered the women to wear their best dresses of a certain style, robe de chambre, and to place many decorative stones in their hair.”60 By going out of his way to imitate Siamese and Persian guest rituals in his own reception of ambassadors, Louis XIV asserted his domination through the reappropriation of foreign customs, reenacted through the prism of French étiquette. In this process, Louis XIV was presented “as an omnipotent Asian despot”61, as the equal or even the superior of the Persian Shah or the Siamese king. This practice also fulfills the function of comparison to far away sovereigns, through which power display is channeled. By imitating, and almost becoming an Asian despot himself, Louis XIV is best able to complete the act of mirroring, to “see himself as through the eyes of the other”62, which is fundamental “to the construction of the monarchy at home”.

Conclusion

Without expanding too much on the three embassies’ historiography, it is nonetheless interesting to note that they have later come to be used to criticize both sovereigns’ rule. The Marquis d’Argenson (1694-1757) would quote the lavish manner in which the Siamese and Persian embassies have been received by Louis XIV as proof that the Sun King “raised his court on a foundation of Asiatic luxury which he could not sustain.”63 The Marquis de La Fare (1687-1752) would describe the monarch as “an imitator of the kings of Asia, whom slavery alone pleased; he ignored merit; his ministers no longer thought of telling the truth, but only to flatter and please him”64. Centuries later, at the bicentennial commemoration of the Macartney embassy, Alain Peyrefitte along with Du Jiang, Guo Chengkang, and Liu Yuwen would paint the Macartney embassy as a missed opportunity for Chinese modernization. Rendering Qianlong’s apparent conservativeness the major culprit in “China backwardness”, the embassy became “part of a cautionary tale. China must never again repeat the folly of the Qianlong court.”65

Qianlong’s and Louis XIV’s guest rituals posit a certain number of similarities, as we’ve demonstrated across this paper. Sharing common conceptions on the function of the guest ritual (expressing domination at home and abroad), the two rulers have exhibited parallel behaviors and imperial ambitions. Highlighted in this article is the essential feature of sight which both give and define royal and imperial power in the guest ritual. Embassies represent an unique opportunity to project power, for the guest sovereign as well as for the host. They also involve many more players who have not been mentioned in this paper, but are as important, such as missionaries who had a pivotal influence in diplomatic relations during the 17th and 18th century, by shaping cultural representations of foreign countries66.

Juliette WU-VIGNOLO

ANNEXES

Positions of each participant in the audience of the Siam embassy at the Galerie des Glaces, 1686. Extracted from the Mercure Galant, special edition: 1) The first ambassador. 2) The second ambassador. 3) The third ambassador. 4) The Marshal de la Feuillade. He had rank at this audience, because the marshals of France being named each one in turn to receive the extraordinary ambassadors extraordinary, according to this order, M. de a Feuillade accompanied the ambassadors. He was between the first and the second. But even though it was his place, he did not cut them off not quite cut them in front of the King. 5) the Marshal Duke of Luxembourg. He was directly behind the first ambassador, in the capacity of Captain of the guards of the body in quarter, who had received the ambassadors at the door of the Hall of the Guards, and who had led them to the foot of the throne of the King. 6) Mr. de Bonneuil, introducer of the ambassadors. 7) Mr. Torf, ordinary gentleman of the Household of the King, appointed to go to receive the ambassadors when they were entered in France, and to accompany them until their reembarkation. 8) the abbot of Lionne. He had no rank in this ceremony only because he served as interpreter. After having interpreted aloud the harangue of the ambassador, he went up to the King to hear the answer of answer of His Majesty. 9) Mr. Giraut, whose place is not quite fixed, and whose care whose care obliges him to be sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other. 10) six mandarins. 11) those who bore the marks of dignity of the ambassadors. There were still several followers, but they were more distant, and were not in his enclosure.

Portrait of the 1st Siamese ambassador. Charles Le Brun. 1686.

Almanach of 1687 depicting the audience granted by Louis XIV to the Siamese ambassadors.

Persian embassy of 1715. Antoine Coypel. Around 1715.

William Alexander’s drawing of the reception of the Macartney embassy to China. Young Thomas Staunton (kneeling not kowtowing) receives a gift from the Emperor.

James Gillray, published on September 14th 1793. « A caricature on Lord Macartney’s Embassy to China and on the little which the Ambassador and his government are presumed to have known of the manners and tastes of the people they wanted to conciliate (the purpose of the visit was to propose the creation of a permanent English mission to the court of Peking). Chinese etiquette is, that extreme prostrations should be made before the Emperor, which it was intimated Lord Macartney would not conform to. The whole contour of the Emperor is indicative of cunning and contempt and his indifference to the numerous gifts displaying the skill of British manufacturing, is evident.

FOOTNOTES

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1. pp. 377-378. ↩︎

- Voltaire. 1957. Le Siècle de Louis XIV. Paris, Gallimard, « Bibliothèque de la Pléiade ». p. 756. Dans : Castelluccio, Stéphane. « Louis XIV, Le Siam et La Chine : Séduire et Être Séduit ». p. 27. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 1”. pp. 25-27. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 5: Guest ritual and interdomainal relations”. pp. 125-133. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. Canadian Journal of History. ↩︎

- Louis XIV, Mémoires pour l’instruction du Dauphin (pp. 136-144) in: Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. p. 192. ↩︎

- Elias, Norbert. 1939. Sur le processus de civilisation. [Publié en deux parties en français : La Civilisation des moeurs & La dynamique de l’Occident]. ↩︎

- Thomas, Greg. “Yuanming Yuan / Versailles: Intercultural interactions between Chinese and European palace cultures”. p. 120. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 2: A multitude of lords”. pp. 30-31. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 2: A multitude of lords”. pp. 37-49. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. 1996. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. Canadian Journal of History. p. 192. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 2: A multitude of lords”. pp. 37-49. ↩︎

- Ibid. “Chapter 5: Guest ritual and interdomainial relations”. pp. 125-133. ↩︎

- Camus, Alice. 2013. « Être reçu en audience chez le Roi ». p. 10. ↩︎

- Annexes (see fully translated original caption). ↩︎

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1. pp. 396-396. ↩︎

- Thomas, Greg. “Yuanming Yuan/Versailles: Intercultural interactions between Chinese and European palace cultures”. p. 118. ↩︎

- Thomas, Greg. “Yuanming Yuan/Versailles: Intercultural interactions between Chinese and European palace cultures.” p. 119. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 7: Convergence – Audience, Instruction, and Bestowal”. pp. 167-176. ↩︎

- Camus, Alice. 2013. « Être Reçu En Audience Chez Le Roi ». p.11. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 6: Channeling along a centering path – Greetings and Preparation”. p. 144. ↩︎

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1. p. 152 : “être défrayés pendant tout leur séjour aux dépens du Roi”. ↩︎

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1. p. 375. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 7: Convergence – Audience, Instruction, and Bestowal”. ↩︎

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. « La Galerie des Glaces. Les réceptions d’ambassadeurs ». p. 24. ↩︎

- Guo Fuxiang (郭福祥). “Presents and Tribute: Exploration of the Presents given to the Qianlong Emperor by the British Macartney Embassy”. p. 146. ↩︎

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. « Louis XIV, Le Siam et La Chine : Séduire et Être Séduit ». p. 28. ↩︎

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. « A propos des canons siamois offerts à Louis XIV qui participèrent à la prise de la Bastille ». p. 328. ↩︎

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. « La Galerie des Glaces. Les réceptions d’ambassadeurs ». p. 43. ↩︎

- Guo Fuxiang (郭福祥). “Presents and Tribute: Exploration of the Presents given to the Qianlong Emperor by the British Macartney Embassy”. p. 143. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 8: Bringing affairs to a culmination”. pp. 192-202. ↩︎

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1. p. 59. ↩︎

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. « Louis XIV, Le Siam et La Chine : Séduire et Être Séduit ». p. 26. ↩︎

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. « La France et Le Siam de 1680 à 1685. Histoire d’Un Échec ». p. 258. ↩︎

- Martin, Meredith. “Mirror Reflections: Louis XIV, Phra Narai, and the Material Culture of Kingship”. p. 664. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 10: From events to history, the Macartney embassy in the historiography of Sino-Western relations”. ↩︎

- Ibid. “Chapter 4: King Solomon in all his glory”. pp. 108-115. ↩︎

- Choisy (François Timoléon de), Mémoire pour servir à l’histoire de Louis XIV. p.152. Dans Castelluccio, Stéphane. « La Galerie des Glaces. Les réceptions d’ambassadeurs ». p. 33. ↩︎

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. « Louis XIV, Le Siam et La Chine : Séduire et Être Séduit ». p. 30. ↩︎

- Duc de Saint-Simon, Mémoires. pp. 404-405. Dans : Mokhberi, Susan. (2012). “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. p. 79. ↩︎

- Baron de Breteuil, Mémoires. Dans : Castelluccio, Stéphane. « La Galerie des Glaces. Les réceptions d’ambassadeurs« . p. 43. ↩︎

- Anthony Colantuono dans Zhao, Bing, et Fabien Simon. « Les cadeaux diplomatiques entre la Chine et l’Europe aux XVIIe -XVIIIe siècles. Pratiques et enjeux ». p. 14. ↩︎

- Latour dans Zhao, Bing, et Fabien Simon. « Les cadeaux diplomatiques entre la Chine et l’Europe aux XVIIe -XVIIIe siècles. Pratiques et enjeux ». p. 12. ↩︎

- Guo Fuxiang (郭福祥). “Presents and Tribute: Exploration of the Presents given to the Qianlong Emperor by the British Macartney Embassy”. p. 155. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 1: Introduction”. pp. 25-27. ↩︎

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, « Par-delà l’incommensurabilité: pour une histoire connectée des empires aux temps modernes », Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 5, n° 54-5 (2007). pp. 34-53. Dans : Mokhberi, Susan. “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. p. 56. ↩︎

- Mokhberi, Susan. “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. p. 57. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. p. 198. ↩︎

- Baron de Breteuil, Mémoires. p. 115. ↩︎

- Mokhberi, Susan. “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. p. 74. ↩︎

- Catherine Bell quoted in: Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 1: Introduction”. pp. 20-25. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 3: Planning and organizing the British embassy”. pp. 60-62. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 1: Introduction”. pp. 25-27. ↩︎

- Sabatier, Gérard. « Le Mythe de Versailles et l’Europe des Cours, XVIIe-XXe Siècles ». p. 1. ↩︎

- Kerssenbrock-Krosigk, Dedo von. 2007. “Glass for the King of Siam: Bernard Perrot’s Portrait Plaque of King Louis XIV and Its Trip to Asia.” Journal of Glass Studies. ↩︎

- Martin, Meredith. “Mirror Reflections: Louis XIV, Phra Narai, and the Material Culture of Kingship”. pp. 657-658. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 6: Channeling along a centering path – Greetings and Preparation”. pp. 134-144. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. p. 173. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. p. 195. ↩︎

- Mokhberi, Susan. “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. p. 78. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. p. 197. ↩︎

- Hostetler, Laura. “A Mirror for the Monarch: A Literary Portrait of China in Eighteenth-Century France”. Asia Major. p. 352. ↩︎

- Voyer de Paulmy, René-Louis, marquis d’Argenson. Mémoires et journal inédit du marquis d’Argenson. Volume 5. 1857-1858. Paris. pp. 352-353. ↩︎

- Love, Ronald S. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. Canadian Journal of History. p. 198. ↩︎

- Hevia, James Louis. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. “Chapter 10: From events to history, the Macartney embassy in the historiography of Sino-Western relations”. pp. 139-144. ↩︎

- Constantin Phaulkon, Phra Narai’s prime minister, would prove especially interesting, seeing as he was the initial advocate for a Siamese embassy to France. ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Camus, Alice. 2013. « Être reçu en audience chez le Roi ». Bulletin du Centre de Recherche du Château de Versailles, Juillet.

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. 2006. « La Galerie Des Glaces. Les Réceptions d’Ambassadeurs ». Versalia. Revue de La Société Des Amis de Versailles 9 (1). pp. 24–52.

- Castelluccio, Stéphane. 2019. « Louis XIV, Le Siam et La Chine : Séduire et Être Séduit ». Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, n° 43 (Décembre). pp. 25–44.

- Cissé, Gérard. 2018. « Focus : l’Ambassade de Siam en 1686. Brest ».

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon (1638-1720 ; marquis de) & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de (1675-1755) Saint-Simon. 1854. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 1 / Publié En Entier Pour La Première Fois Par MM. Soulié, Dussieux, de Chennevières, Mantz, de Montaiglon ; Avec Les Additions Inédites Du Duc de Saint-Simon Publiées Par M. Feuillet de Conches.

- Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon (1638-1720 ; marquis de), & Louis de Rouvroy, duc de (1675-1755) Saint-Simon. 1854. Journal Du Marquis de Dangeau. Tome 2 / Publié En Entier Pour La Première Fois Par MM. Soulié, Dussieux, de Chennevières, Mantz, de Montaiglon ; Avec Les Additions Inédites Du Duc de Saint-Simon Publiées Par M. Feuillet de Conches.

- Finlay, John. 2019. “Henri Bertin and Louis XV’s Gifts to the Qianlong Emperor”. Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, n° 43 (Décembre). pp. 93–112.

- Guo Fuxiang (郭福祥). 2019. “Presents and Tribute: Exploration of the Presents given to the Qianlong Emperor by the British Macartney Embassy”. Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, n° 43 (Décembre). pp. 143–72.

- Hevia, James Louis. 1995. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. Durham, North Carolina : Duke University Press Books.

- Hostetler, Laura. 2006. “A Mirror for the Monarch: A Literary Portrait of China in Eighteenth-Century France”. Asia Major 19 (1/2). pp. 349–76.

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. 1985. « A propos des canons siamois offerts à Louis XIV qui participèrent à la Prise de la Bastille ». Annales Historiques de La Révolution Française 261 (1). pp. 317–34.

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. 1995. « La France et le Siam de 1680 à 1685. Histoire d’un échec ». Outre-Mers. Revue D’histoire 82 (308). pp. 257–75.

- Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel. 1984. « Les Ambassadeurs Siamois à Versailles, le 1er septembre 1686, dans un bas-relief en bronze d’A. Coysevox ». Journal of the Siam Society, n° 72. pp. 19-35.

- Kerssenbrock-Krosigk, Dedo von. 2007. “Glass for the King of Siam: Bernard Perrot’s Portrait Plaque of King Louis XIV and Its Trip to Asia”. Journal of Glass Studies, n° 49. pp. 63–79.

- Love, Ronald S. 1996. “Rituals of Majesty: France, Siam, and Court Spectacle in Royal Image-Building at Versailles in 1685 and 1686”. Canadian Journal of History 31 (2). pp. 171–98.

- Martin, Meredith. 2015. “Mirror Reflections: Louis XIV, Phra Narai, and the Material Culture of Kingship”. Art History 38 (4). pp. 652–67.

- Mokhberi, Susan. 2012. “Finding Common Ground Between Europe and Asia: Understanding and Conflict During the Persian Embassy to France in 1715”. Journal of Early Modern History. n° 16. pp. 53-80.

- Rochebrune, Marie-Laure de. 2019. « Les porcelaines de Sèvres envoyées en guise de cadeaux diplomatiques à l’Empereur de Chine par les souverains français dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle ». Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, n° 43 (Décembre). pp. 81–92.

- Sabatier, Gérard. 2016. « Figures de l’Étranger à Versailles ». Bulletin du Centre de Recherche du Château de Versailles, Juillet.

- Sabatier, Gérard. 2020. « Le Mythe de Versailles et l’Europe des Cours, XVIIe-XXe Siècles ». Bulletin du centre de recherche du Château de Versailles. Sociétés de cour en Europe, XVIe-XIXe Siècle, Décembre.

- Thomas, Greg. 2009. “Yuanming Yuan/Versailles: Intercultural interactions between Chinese and European palace cultures”. Art History. n° 32. pp. 115-143.

- Zhao, Bing & Fabien Simon. 2019. « Les cadeaux diplomatiques entre la Chine et l’Europe aux XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles. Pratiques et enjeux ». Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident. n° 43. pp. 1. 5-24.

No Comment