By Jules DESMARS

In the energy realm, few topics evoke as much debate and division as the exploitation of shale gas. Positioned as a crucial asset for powering nations and providing essential heat, its extraction also stirs a cauldron of environmental and social dilemmas, fueling political unrest. The urgent need to strike a balance between environmental stewardship and meeting human demands looms large on the global agenda. However, the ramifications extend beyond policy debates. Communities residing near extraction sites bear the brunt of its environmental fallout, raising profound questions of social justice. While the European Union (EU) discourages shale gas exploitation, particularly through controversial methods like fracking, certain Member States adopt a divergent stance when engaging in foreign relations. Notably, since 2013, Algeria has become embroiled in an environmental tug-of-war over its shale gas reserves, a conflict that has largely escaped international scrutiny. As we delve into this case, it becomes evident that the discourse surrounding shale gas transcends borders, underscoring the imperative for global attention and dialogue.

Environmental Conflict and Shale Gas Fracking

The core focus of this paper is on the environmental conflict caused by the exploitation of shale gas in Algeria and the EU ambivalent position. Le Billon defines environmental conflicts broadly, classifying it as a social conflict relating to the environment (2015). However, there are variations to this definition. One of the main forms of conflict Le Billon looks at is conflict over the environment, about the use of resources. He draws upon Turner’s definition stating that environmental conflicts are violent or nonviolent social conflicts connected to both the dispute over access to natural resources and the conflicts brought on by their utilization (2004). To better understand what environmental conflicts are, Le Billon uses the ‘resource curse’, a scarcity-driven argument according to which the exploitation of abundant resources in economies with little economic diversification leads to resource reliance, which heightens conflict susceptibility (2015). Thus this extensive definition of environmental conflict fits the dispute over shale gas exploitation in Algeria, an abundant resource over which the country relies heavily without variegating its economic activities.

Concerning shale gas fracking, The EU Recommendation 2014/70/EU provides a formal definition, stating that: “Shale gas is trapped within rock structures, which need to be broken open to extract the gas. The process used for this is hydraulic fracturing or fracking. It involves cracking open the rock by inserting high volume water, sand, or chemicals into a borehole.”

This definition has been completed by scientists that have also looked at shale gas from a different perspective, one that contemplates both human health and environmental protection. Shale gas extraction and consumption increase environmental risks, such as water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution.1 In effect, the process of hydraulic fracturing, as seen in the EU definition, implies the injection of chemicals in a borehole, straight into the underground. The chemicals used in the process could contaminate underground sources of drinking water, therefore having a dual impact both on the environment and on human health (Finkel & Hays, 2013). Natural gas activities have been linked to several claims of respiratory, neurological, reproductive, dermatological, gastrointestinal, and other health problems that harm human health (Finkel & Hays, 2013). Lastly, hydraulic fracturing and consumption of shale gas also have an adverse effect on air quality, increasing the quantity of methane and pollutants in the atmosphere (Wang, Yang & Wang, 2015). Therefore, it can be assumed that shale gas production through hydraulic fracturing and its consumption are harmful both for the environment and human health.

Lastly, hydraulic fracturing and consumption of shale gas also have an adverse effect on air quality, increasing the quantity of methane and pollutants in the atmosphere (Wang, Yang & Wang, 2015). Therefore, it can be assumed that shale gas production through hydraulic fracturing and its consumption are harmful both for the environment and human health.

Shale Gas Conflict in Algeria

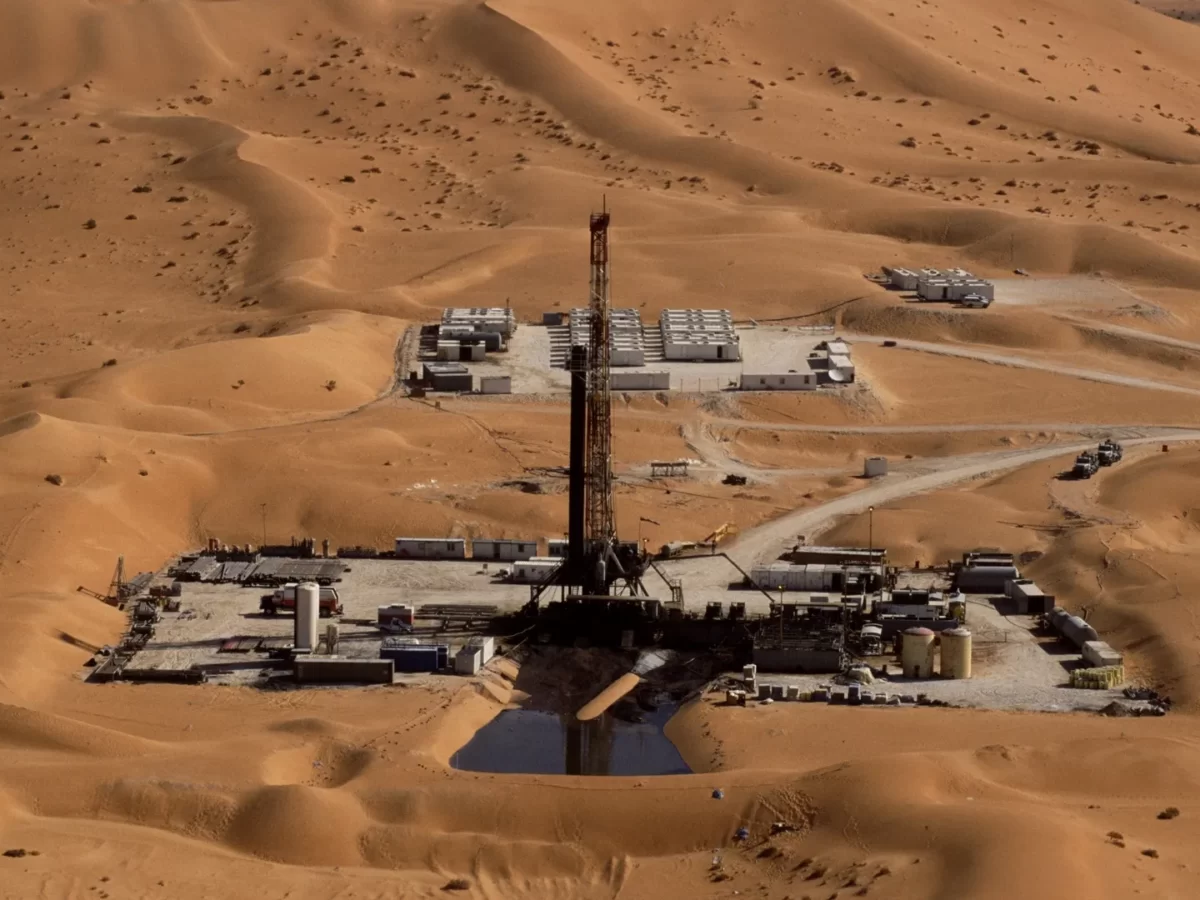

Historically, Algeria always had important resources as can be witnessed by the discovery of major oil reserves in 1953. Algeria used these resources as a catalyser to grow its economy and position itself as a great economic power in the Southern Mediterranean (Boersma et al., 2015). Algeria holds immense shale gas resources. In 2013 an EIA-sponsored study estimated that there are 707 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas resources (Boersma et al., 2015), making it the third largest country in the world as regards recoverable shale gas reserves (Boudalia et al., 2022). To put this into perspective, Algeria’s hydrocarbons industry represents about 60% of its budget income, 30% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and more than 97% of its export earnings (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). These immense resources are mainly located in the Sahara desert (Boudalia et al., 2022; Aczel, 2020). In 2013, to encourage international businesses to invest in Algeria, the National Assembly amended the country’s hydrocarbon legislation, allowing for the development of unconventional hydrocarbons (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). This amendment led the Algerian Minister of energy – Yousfi – to announce the beginning of exploratory drilling by Sonatrach in December 2014. These first drills were met with violent protests, starting at the local level before spreading throughout the country. In effect, between 2014 and 2015, there have been uprisings in the Sahara region, notably, anti-fracking protests. (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). To halt these protests, the Algerian government announced to temporarily stop the exploitation of shale gas. However, in October 2017, Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia encouraged Sonatrach, a state-owned oil company to restart exploratory drilling. Such action was supported by France, incentivising Total, its main energy company which signed an agreement in 2017 with Sonatrach, to strengthen their ‘comprehensive partnership’. (Aczel, 2020). The EU increased its energy ties and hence its dependency on Algeria when the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out in February 2022. Algeria is among the countries with which the EU passed supplementary energy agreements since the outbreak of the war, seven to be precise.

In terms of destination, Algeria is an important exporter of gas to the EU, accounting for 14% of the EU’s gas imports, and 10% of its consumption. Portugal, France, Italy, and Spain are among the states importing the most gas from Algeria (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016).

The main issue here is the environmental risk caused by the exploitation and consumption of shale gas at the expense of minorities living near the factories on top of the uneven redistribution of resources. Its exploitation presents three main risks: water scarcity in arid regions, underground water pollution, and air pollution. On top of the risks associated with exploitation, it also produces greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to climate change (Zhang & Tingyun, 2015). As emphasized by Boudalia et al., environmental concerns are among the most important ones to explain protests. Furthermore, Algerian populations are aware of alternative sources of energy, potentially able to replace shale gas exploitation such as solar panels, questioning the willingness of the Algerian government to protect the environment, knowing that this latter ratified the Paris Agreement. (2022).

Beyond environmental concerns, the protests are also social. A combination of high unemployment levels in the region, with a lack of transparency at the government level, and issues of corruption, has increased the salience of the conflict (Aczel, 2020). For example, the government uses oil and gas revenues to co-opt and repress demands for reforms voiced by civil society. The Algerian government is rated 3.66/10 on the democratic index, 10 being the best form of democracy achievable (Democracy Index, n.d.). The Algerian political regime is best described by Hamouchene and Pérez as one that imposes limitations on liberties and disrespects political and human rights of activists, all while the governing class is corrupt (2016). Thus there is a double conflict, both environmental and social.

The EU’s position duality

The EU position is quite ambivalent. Through recommendation 2014/70/EU, the European Commission wishes to introduce “proper safety and environmental safeguards” before undertaking shale gas fracking.2 Besides, it condemned Poland in 2018 for not having conducted a proper evaluation concerning the environmental impact assessment of shale gas exploitation.3 Therefore, at first, the EU seems to tolerate the exploitation of shale gas solely under certain safety conditions. The EU position is reflected in France’s decision to implement Loi Jacob in 2011 banning fracking. Yet surprisingly the EU adopts with Algeria a contradictory policy, encouraging the exploitation in the country (Aczel et al., 2018). For the EU, Algeria is nothing more than a strategic partner because of its oil and gas resources. Following Russia’s invasions of Ukraine, first in the Crimea region in 2014 and later on the country scale in 2022, the EU reconsidered its energy partnerships and rerouted its gas imports (Sauvageot, 2020; European Commission, 2023), notably towards Algeria. The Covid-19 crisis also contributed to the EU increasingly needing energy sources (European Commission, 2023). Such ambivalence can be explained by the EU treaties, that put environmental protection below safeguarding energetic independence, as enshrined in article 194(2) TFEU (Aczel et al., 2018). Therefore, it can be argued that the main preoccupation of the EU and its member states is to secure energy supplies and their diversification.

EU Member states use energy companies as foreign policy tools by EU Member States (Peter, 2003). It can be argued that they use these national energy companies (not necessarily nationalized) to secure their energy supplies. However, most of these companies are involved in embezzlement, fraud, or bribery. For instance, Sonatrach, the Algerian state-owned oil company is embroiled in corruption scandals, while SAIPEM, an Italian company, has been prosecuted for bribery (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). Thus, most of the companies involved in the business of shale gas give little attention to environmental protection and a lot to making profits.

Additionally, Algeria is a so-called rentier state, living on its resources’ exploitation and rent. For instance, despite the nation’s socio economic issues, the administration was able to survive the Arab Spring owing to the non-transparent circumstances of their wealth redistribution (Aczel et al., 2018). The Algerian government uses shale gas revenues as a way to stay in power undemocratically and to position itself as a strong regional power. And despite Algeria’s classification as an illegitimate anti-democratic system, the EU, which claims to work with Algeria, supports the regime. Indeed, the EU keeps ignoring the social movements and civil society, to instead court the Algerian regime and secure its energy supplies. (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). Lastly and perhaps most importantly, it appears that Algeria has been using its energy resources as political leverage on the EU gas importers for it to receive support economically and politically in Western Sahara (Kardas, 2023).

Such a situation has a direct impact on local populations. The Sahara, an oil-rich region that supplies the majority of Algeria’s resources and state income but has long been marginalized politically, economically, and culturally, has seen a rise in discontent since 2012. The National Committee for the Defence of Unemployed Rights, or CNDDC, spearheaded the protests. (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016 & Boudalia et al., 2022). Besides, local populations, for explicit reasons — inequalities, groundwater contamination, environmental damage — are willing to halt the extraction of shale gas. Moreover, they view shale gas extraction operations as a danger to their lives since they depend mostly on land use (pasturage and agriculture), which is vital for them (Hamouchene & Pérez, 2016). Therefore, local populations require more transparency and more considerations from the government, socially, culturally, and environmentally.

Conclusion

In sum, the EU, as enshrined in its law, prioritizes energy security over the protection of the environment and the defence of civil rights of the Algerian local population. Such action is contradictory with the application of EU law internally as can be witnessed with the case of Poland being sanctioned and the recommendation 2014/70/EU that requires the implementation of safety measures prior to the exploitation of shale gas. Besides, article 2 TEU claims that the EU is based on values such as respect for human dignity, human rights and democracy.4 Yet, as explained previously, the EU supports the Algerian government, qualified as an undemocratic regime with a democratic score of 32/100 (Freedom House, 2024). Thus such support also reflects how important energetic supply is to the EU and what sacrifices the EU is capable of making. Such a situation can be reflected in the fact that the EU has increased its energy ties with Qatar, rated 25/100 by Freedom House in 2024. Therefore, the EU ambivalence in terms of environmental and democratic standards is reflected in the exploitation of shale gas in Algeria but not only as it witnesses the increase of ties with Qatar in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war.

By Jules DESMARS

NOTES

- Zhang and Tingyun, 2015; Boudalia et Al., 2023; Boersma & Vandendriessche, 2015; Aczel et al., 2018. ↩︎

- Commission Recommendation 2014/70/EU Fracking: minimum principles for the exploration and production of hydrocarbons using high-volume hydraulic fracturing. ↩︎

- Case C-526/16 European Commission v Republic of Poland [2018] ECLI:EU:C:2018:356. ↩︎

- Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union – TITLE I COMMON PROVISIONS – Article 2. ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aczel, M. R. (2020). Public opposition to shale gas extraction in Algeria: Potential application of France’s ‘Duty of Care Act’. The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(4), 1360-1368.

- Aczel, M. R., Makuch, K. E., & Chibane, M. (2018). How much is enough? Approaches to public participation in shale gas regulation across England, France, and Algeria. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(4), 427-440.

- Boersma, T., Vandendriessche, M., & Leber, A. (2015). Shale Gas in Algeria – No Quick Fix. Brookings.

- Boudalia, S., Okoth, S. A., & Zebsa, R. (2022). The exploration and exploitation of shale gas in Algeria: Surveying key developments in the context of climate uncertainty. The Extractive Industries and Society, 11, 101115.

- European Commission. (2023). Europe’s Energy Security. In Search of Supply Independence From Russia. Przedstawicielstwo W Polsce.

- Finkel, M. L., & Hays, J. (2013). The implications of unconventional drilling for natural gas: a global public health concern. Public health, 127(10), 889-893.

- Freedom House. (2024). Algeria. In Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/algeria/freedom-world/2024

- Freedom House. (2024). Qatar. In Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/algeria/freedom-world/2024

- Hamouchene, H., & Pérez, A. (2016). Energy Colonialism: The EU’S Gas Grab in Algeria. The Observatory on Debt and Globalisation.

- Kardas, S. (2023). Keeping the lights on: The EU’s energy relationships since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. ECFR. https://ecfr.eu/publication/keeping-the-lights-on-the-eus-energy-relationships-since-russias-invasion-of-ukraine/

- Le Billon, P. (2015). Environmental conflict. In The Routledge handbook of political ecology (pp. 598-608). Routledge.

- Sauvageot, E. P. (2020). Between Russia as producer and Ukraine as a transit country: EU dilemma of interdependence and energy security. Energy Policy, 145, 111699.

- Turner, M.D. (2004). “Political ecology and the moral dimensions of ‘resource conflicts’: the case of farmer–herder conflicts in the Sahel”. Political Geography 23(7): 863–889.

- Wang, L. K., Yang, C. T., & Wang, M.-H. S. (2015). Hydraulic Fracturing and Shale Gas: Environmental and Health Impacts. In Advances in Water Resources Management (Vol. 16, pp. 293–337). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22924-9_4

- Zhang, D., & Tingyun, Y. A. N. G. (2015). Environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing in shale gas development in the United States. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 42(6), 876-883.

No Comment