Hollywood, the epitome of the United States’ global power

Translated from the article written by Lino HEIDBRINK and Marion NOËL

Hollywood is a film industry that has been making more than 500 movies per year for many decades. These movies are consistently among the top ten of the international box office. Such a success allows Hollywood to be in a leading position on the international film market. However, how come Hollywood thrives and displays so much cinematographic power? By broadcasting American values and geopolitical stances worldwide, Hollywood is no doubt a tool for the United States’ soft power.

I) Hollywood on a global quest…

The worldwide expansion

Hollywood’s studios were built in 1914 in Los Angeles, California. In order to optimize the filming and to reduce production costs, Hollywood swiftly adopted “Taylorism”, a new management theory. The script became a specification in which the storytelling, its length and purpose all depend on the means of production and on the actors playing a role in and outside the movie. Task fragmentation and job diversification lead to a specialization by sectors called clusters. The majors were parent companies in charge of the management, the finances and the film economy. Gradually, several majors regrouped and Hollywood became a film industry. There were two cartels of majors in Hollywood. First the MPAA-Motion Picture American Association (1922), which made decisions surrounding the broadcasting of movies in the US and Canada. Then, the MPEA-Motion Picture Export Association (1945) was in charge of the distribution abroad. Between 1950 and 1970, the latter focused on Japan and Europe to broadcast Hollywood movies. As early as 1970, Hollywood began to develop an international network throughout the new globalization phenomenon and reorganized itself with new strategies. Three main reasons seem to explain Hollywood’s expansion on the international stage.

The first reason is the opening of the international film market to foreign investors and the free movement of capital. As soon as 1980, The majors were bought by foreign multinational companies. For instance, Columbia was first repurchased by the Japanese firm Matsushita, then by Vivendi. Universal is yet another example. The studio was repurchased by Sony. In the meantime, foreign markets also opened, allowing Hollywood to invest in foreign movie theaters – multiplex -. Moreover, the majors start to open subsidiaries abroad. A global network was soon to be witnessed.

The second reason is the gradual opening of previously closed markets like South Korea. In the 1980’s, Hollywood’s products amounted to less than 35% of market shares in the country. Since 1990, almost half the Korean national market’s shares are attributable to Hollywood. Nowadays, South Korea is one of the ten main markets for Hollywood. Moreover, free-trade agreements with multiple countries foster Hollywood’s expansion for it allows movies to reach a wider audience.

The third one is the use of data through analysis of the international audience. As requested by Hollywood, the National Research Group founded in 1978 performed various market researches. The purpose of the studies was to decrypt the spectators’ tastes according to their age, ethnicity and gender. The institute is said to have spearheaded such studies and underlines its role in the distribution and in the sales of Hollywood’s movies across the world.

As a result, since the end of the 1990’s, Hollywood’s financial gains are far more important on foreign markets than on the domestic one. Furthermore, Hollywood possesses between 60% and 75% of shares of the international film market.

Evolution of the distribution channels

Hollywood’s movies were first distributed in movie theaters. Since the 1980’s and the democratization of the television audience, anyone can watch them at home. On top of that, the rise of pay-TV channels in the 1990’s in Europe allowed Hollywood not only to thrive financially, but also to reach an even broader audience, even faster. Another policy dictated that private channel owners who wanted to buy the rights to a single movie had to purchase at least a dozen movies. In the early 20th century, VHS tapes, DVDs and the fast-growing and uncontrolled internet – through illegal streaming services, illegal download platforms for instance – explained Hollywood’s expansion on the international film market. This became a new era of movie distribution.

II) … to spread the United States’ vision…

Within the MPAA and MPEA are political elites with close ties to Washington. Hollywood’s construction and conquest of the world come along with strong lobbying aimed at Congress and the American government. But this also benefits the American leaders who find in this relationship a way of propagating the values defended by the United States, as well as a certain vision of the world. Hollywood is definitely a tool of soft power.

The government’s footprint

In the 1910’s, Hollywood films were intended for a poor, immigrant audience. Films such as The Immigrant (1917) and westerns recounted American history and nation-building. They promoted patriotism, religious and family values, and hard work. These images aimed to unite people from different backgrounds and cultures around the same values. The United States’ political sphere soon became involved in cinema: in 1934, Senator William Harrison Hays introduced the Hays Code into films. The United States, or any allegory of it, must be portrayed in a « respectful » manner. Under no circumstances should criminals attract sympathy. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act brought diversity to the screen by establishing quotas for actors of different skin colors. The quest for making American values universal was launched.

Charlie Chaplin, playing an immigrant coming to the US, in The Immigrant – Source: Letterboxd

Since the Second World War, the US government financed movies aimed towards national security topics. The produced films fight against Nazi ideology or denounce the Communist threat, awakening citizens’ patriotic feelings. A direct link was established between the War Department and Hollywood. It would never be broken. These films also promoted – and even propagandized – the American army, which lent its equipment and men for filming purposes. The 1986 film Top Gun is a perfect example (translator’s note: as much as its 2022 sequel, Top Gun: Maverick). This film even helped to recruit many American soldiers, with the army setting up recruitment booths at the end of screenings.

Tom Cruise, starring as Pete “Maverick” Mitchell in Top Gun – Source: Imdb

The script: a tale of conflicts and threats

Hollywood films not only unite a nation around the values and geopolitical representations of the United States, but also the entire world. The conflicts and threats that the United States and its allies face are scripted. Plots dating back from the second half of the 20th century battle Nazi ideology and the Communist enemy during the Cold War. Cinema was part of the logic of the National Security State Doctrine, put in place under the Truman administration. The scenarios also illustrate the shift and evolution of conflicts and threats. Cyber-attacks, the threat of terrorism, drug trafficking and gangs have all been featured in plots since the 2000’s.

Furthermore, the films provide an American representation of history by using heroic figures. Examples include Rambo 2, about the Vietnam War, and Rambo 3, about the war in Afghanistan. These films also serve to attenuate – or even glorify – the role of the American army in conflicts: American Sniper, released in 2015, pays tribute to a soldier who took part in the conflict in Iraq (translator’s note: one could also mention Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant, released in 2023).

Chris Kyle, the deadliest marksman in US military history, leaving his wife Taya in American Sniper – Source: Archer Avenue

It is relevant to look at the stylistic evolution of both films and characters. Over the past few years, superhero films have been proliferating, consistently topping the box-office. Since 2012, the screen adaptation of The Avengers has been a resounding success (translator’s note: in 2019, the 22nd film of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Avengers: Endgame, became the highest-grossing film of all time). It features Captain America, a patriotic superhero created during the Second World War to embody the United States’ fight against nazism. Is it related to the fight against terrorism? Superhero figures are once again used in times of armed and ideological conflict.

Captain America coming back victorious to the Allied camp, after releasing soldiers that were detained by the Nazi army in Captain America: The First Avenger – Source: Fanpop

The « Allies » on screen

The spread of Hollywood films on the international scene has led to changes in on-screen representations. Clint Eastwood’s films about the battle of Pearl Harbor is a good example: Flags of Our Fathers, released in 2006, favors American representation, while Letters from Iwo Jima, released in 2007, favors Japanese representation. The box-office successes of these two films seem to be quite revealing: Flags of Our Fathers topped the box-office in the USA and Letters from Iwo Jima topped the box-office in Japan.

The poster for the American film is inspired by the famous photograph « Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima », which immortalized the victory of the United States. The Japanese poster is more soothing, even peaceful – Source: Letterboxd

From the 1980s onwards, scenarios have included allied countries, and crime has become a transnational affair. Until then, plots only featured the United States, alone against an enemy. Scenarios started to adapt to the relationships forged between the United States and its allies. The 2015’s James Bond film, Spectre, was partly shot in Mexico City. The Mexican government set certain conditions: the lead actress had to be Mexican, the villain had to be non-Mexican, and the city’s modernity had to be emphasized.

In Spectre, Mexico City is portrayed as modern and lively, in the midst of a carnival – Source: Cinergetica

Finally, let us consider the influence of the multinational-owned majors on scriptwriting. The takeover of Amblin Partners (Steven Spielberg’s company that groups together his various studios) by the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has been subject to several conditions: the presence of at least one Chinese actor in future films, the shooting of scenes in China and a positive representation of the country.

In this way, Hollywood is perfecting its outreach and integration on the international scene in order to develop its soft power: a strategy of influence to attract, convince and unite public opinion around American values.

III) … but confronted to limits.

Concerns

Hollywood’s expansion into international markets seems worrying for some people. It is accused of not being a cinema of internationalization but of globalization while the free movement of culture in commercial exchanges threatens cultural diversity. UNESCO looked into the problem and, in October 2005, established a convention to defend cultural diversity: the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions – CEDC – which authorizes states to regulate the distribution of foreign films on their territory. The convention has been ratified by 124 countries, including France, Canada and India but not by the United States. Additionally, in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership – TTIP -, the United States turned down any regulation aimed at the film industry.

Closed markets

Hollywood depicts the world in three blocks: « open », « semi-open » and « closed » countries. Hollywood’s foreign markets represented 75 countries in 1979, over 80 in 1990 and more than 150 in 2000. Closed markets can be explained mainly by geopolitical reasons, as was the case for India between 1971 and 1973, or for Spain under Franco: between 1964 and 1967, Columbia was prohibited from distributing its films in the country.

In China, the film industry is controlled by the state, which sets annual quotas for foreign films. Until 2012, the quota was 20 films a year; it is now 45. Moreover, foreign films have to adapt to the Chinese market. Some sequences were cut from Skyfall, released in 2013, and some parts of the film suffer from an inaccurate Chinese translation (translator’s note: in 2016, the movie Doctor Strange whitewashed a major Tibetan character for fear of jeopardizing the title’s chances of success in China). This practice is becoming common, as demonstrated by the new collaboration between Alibaba and Steven Spielberg’s studios.

In Doctor Strange, the character of the Ancient One is played by a Caucasian actress, Tidla Swinton. In the original comics, the character is a Tibetan – Source: Pinterest

A disturbing depiction

For some people, the depictions in Hollywood films like in Argo are disturbing. The film tells the story of the hostage-taking at the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, and aroused fierce criticism in Iran, leading to the signing of an UN-petition, which called for an advert to be broadcast at the start of the film, warning that the story does not accurately portray the events.

In Argo, the airport scene is very intense and suspenseful. In reality, the diplomats had no problem getting their visas checked before boarding their plane – Source: Super Cinema Up

The U.S. government positions itself as the first censor when a Hollywood film broadcasts a representation contrary to the country’s positions. Francis Ford Coppola was the first victim of this censorship during the shooting of his 1979 film Apocalypse Now. The film tells the story of the Vietnam War, and presents an uncompromising, raw war. It was the first time a big-budget film had received no support from the U.S. military. Brian de Palma’s Redacted, released in 2007 and presented at the Mostra, suffered greatly from censorship in the United States. Indeed it portrays the rape of a little girl and the massacre of her family by American soldiers during the 2003 Iraq war. The film takes a clear stand against the war. Brian de Palma was accused of making anti-American propaganda, and the film was released in only 15 American theaters, and quickly disappeared from the American box-office.

This scene from Apocalypse Now, in which US forces are seen bombing civilian villages, may explain why the US military refused to finance the film – Source: Film Affinity

Conclusion

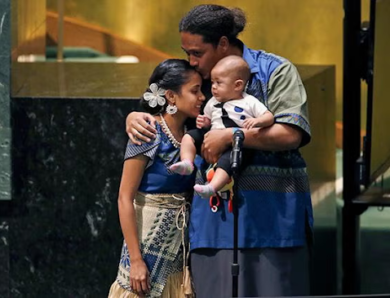

For more than a century, Hollywood has succeeded in anchoring itself in international culture. Thus, in October 2016, the UN chose the American actress Lynda Carter, aka the former Wonder Woman, as an ambassador for the cause of women around the world. Countries that totally or partially close their doors to American cinema sometimes see their citizens get around these bans with the use of the Internet or the support of diasporas. Hollywood cinema is therefore a powerful tool for American soft power on the international stage.

Translated from the article written by Lino HEIDBRINK and Marion NOËL

Bibliography

- MINGANT, Nolwenn. Hollywood à la conquête du monde. Marchés, stratégies, influences. Paris : CNRS Edition, 2010.

- MARTEL, Frédéric, Mainstream, Enquête sur cette culture qui plaît à tout le monde, Flammarion, 2010.

- VALANTIN, Jean-Michel, Hollywood, le Pentagone et Washington. Les trois acteurs d’une stratégie, Editions autrement, 2003.

- DEHÉE, Yannick, « L’argent d’Hollywood », Le Temps des médias 1/2006 (n° 6) , p. 129-142.

- KOCIEMBA, Valérie. « Hollywood mondialise-t-il le regard ? », Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer, 238 | 2007, 257-269.

- VERMEESCH, Amélie. « Poétique du scénario », Poétique 2/2004 (n° 138), p. 2.

- VLASSIS, Antonios. « Ouverture des marchés cinématographiques et remise en cause de la diversité des expressions culturelles », Géoéconomie 3/2012 (n° 62), p. 97-108.

- RAFONI, Béatrice. « Cahiers du cinéma, l’Asie à Hollywood » [En ligne], 2 | 2002, mis en ligne le 23 juillet 2013, http://questionsdecommunication.revues.org/7284 (consulté sept. 2016).

- MINGANT, Nolwenn. « Hollywood au 21e siècle : les défis d’une industrie culturelle mondialisée », Histoire@Politique 2013/2 (n°20), p. 155-167.

- UNESCO, Institut for statistics. « Diversity and the film industry An analysis of the 2014 UIS Survey on Feature Film Statistics », Information paper n°29, March 2016.

- Motion Picture Association of America. « Theatrical market statistics », (from 2006 to 2015).

- « Steven Spielberg se tourne vers la Chine ». Le Monde, mardi 11 octobre 2016, p12.

- Online piracy in numbers – facts and statistics [infographic], Go-Gulf.com, nov. 2011, http://www.go-gulf.com/blog/online-piracy/ (consulté oct. 2016).

- FRENCH, Philip, How 100 years of Hollywood have charted the history of America, theguardian.com, fév. 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/feb/28/philip-french-best-hollywood-films (consulté oct. 2016).

- A code to maintain social and community values in the production of silent, synchronized and talking motion pictures, MPPDA, mar. 1930.

- Most watched movies of all time, IMDb, jui. 2013, http://www.imdb.com/list/ls053826112/ (consulté oct. 2016).

- « Quand les blockbusters d’Hollywood s’adaptent au marché chinois ». INA, avril 2013, http://www.inaglobal.fr/cinema/article/quand-les-blockbusters-d-hollywood-s-adaptent-au-marche-chinois?tq=313-234 (consulté sept. 2016).

- « Qui contrôle vraiment le cinéma chinois ? » INA, nov. 2015, http://www.inaglobal.fr/cinema/article/qui-controle-vraiment-le-cinema-chinois-8668 (consulté sept. 2016).

- «Les majors d’Hollywood : des gardes-barrières centenaires». INA, sept. 2013 http://www.inaglobal.fr/cinema/article/les-majors-dhollywood-des-gardes-barrieres-centenaires#intertitre-6 (consulté sept. 2016).

No Comment