The structure of cryptomarkets provides users with a low-risk environment. This environment is characterized by anonymity and the absence of physical contact which can be critical enablers in the decision to start selling on these markets. In addition to these « reassuring » parameters, vendors might adopt a specific attitude to increase the distance between the offline market with its street selling dealer and them. Indeed, they tend to focus on the various qualities that dealers or the mythical “bad dealer” seem to be lacking. By doing so, they improve their own image at the expense of the street dealer, presented as deviant and dangerous. Online sellers bring out their technical skills, their rationality and responsibility in order to live up to their reputation.

Vendors emphasize their skills and qualities as a way to distance themselves from the image of the “bad dealer”

Vendors show high technical and commercial skills to distinguish themselves from the street dealer level

Cutting edge skills in IT or willingness to learn

In order to sell online, vendors need to have a set of computer-related skills. These skills are the prerequisite to enter cryptomarkets: they function as typical barriers to entry. That is to say, if one does not have them, one will not be able to access cryptomarkets. Potential vendors need a high degree of motivation to learn how the Dark Net works or they need to have already mastered cutting-edge IT skills in order to be anonymous.

In the first case, vendors can acquire the knowledge necessary to penetrate cryptomarkets: forums on the Open Web disclose how Tor networks, Bitcoins and cryptomarkets work. These forums can be linked to the libertarian ideas shared by members of the online communities and prevalent on the different cryptomarkets. [25] However, acting alone without being computer-skilled could increase the chances of being caught, for instance if a mistake is made in the anonymizing process. A seller on cryptomarkets sums up the idea: “the downside as a seller is the fact you have to trust the Tor network to keep you safe. If you are not a computer scientist, a lot is down to just faith. A seller has to learn a lot about the technology, if they are concerned with staying safe.” [26] It highlights the fact that everyone has to be skilled and trust Tor.

In the second case, people can already rely on a specific technical background. These people are generally white men in their 20s and 30s. They are qualified, sometimes employed, and even in some cases have a family.

These technical skills are constitutive elements of a sociological “barrier”, a notion defined by Edmond Goblot. [27] Social demarcation is in part achieved through the existence of a barrier which defines criteria not readily accessible to other members of society. Here computer-related knowledge can be conceptualized as a barrier because offline dealers do not possess it. This knowledge is a key element for online vendors to distinguish themselves from typical drug dealers and gain wider consideration. This barrier is extremely sharp because only a handful of people have this type of knowledge: online vendors form a market niche. Thus, this barrier prevents confusion between two types of drug dealers, on the one hand the “rough” dealer and on the other, the “skilled” dealer, a kind of white-collar criminal.

Commercial choices which reflect vendors’ rationality to keep a fine reputation

Vendors adopt a rational behavior at each stage of a transaction by undertaking a cost / benefit analysis. Indeed, they consistently arbitrate between the risks they are willing to take and their choices. The latter are made based on one’s preferences which are consistent in times. Therefore, vendors’ strategies differ in different aspects, partly because vendors perceive risks differently and are not seeking the same goals (short-term or long-term).

David Décary-Hétu, Masarah Paquet Clouston and Judith Aldridge identify four categories of risk when selling offline: risk of arrest, risk of violence, risk to profits and reputational risk.[28] With cryptomarkets, the risk landscape for vendors involved in drug dealing, has evolved. For example, risks of arrest and of violence are lower thanks to cryptomarkets’ structures, anonymization processes and the absence of face-to-face contact.

In order to cope with these risks, online vendors have adapted their strategies: some of them limit the quantity of drugs as well as the locations where they sell, and tailor their shipping methods according to the risks. For instance, sometimes the quantity delivered is reduced so that it fits in a special packaging (such as “a plain letter envelope” [29]) without being suspicious. Another widespread practice among vendors consist in using drop addresses.

When it comes to selling abroad, vendors also take into account some specific features regardless of the buyer’s profile or identity. For instance, vendors often look at the law enforcement policy in the buyer’s country. Indeed, trends have shown that the higher the expenditures are concerning law enforcement policies, the lower is the probability to agree shipping drugs in this country. [30] Therefore, some vendors decide not to sell in several countries because they consider that the risk is too high when taking into account the law enforcement policy.

Vendors also usually adopt different strategies regarding overseas shipments according to the payment method available to them. Indeed, although “selling internationally may negatively affect a vendor’s rating because of a higher number of intercepted or delayed shipments” [31], some vendors choose to sell abroad anyway especially if they have the possibility [32] to use « finalize early ». Thanks to this method, if the transaction is intercepted by customs the vendor has already the money and the possibility to withdraw from the deal, while buyers are left with no way of complaining about the service provision, so that there is no damage to the seller’s reputation.[33]

As reputation plays a crucial part on cryptomarkets, vendors should do their best to ensure good feedbacks. Therefore, they have an interest in being accountable and efficient sellers.

Vendors emphasize their reputation and responsibility

Vendors emphasize on their responsibility towards their customers in several ways. Some of them highlight that they only sell high quality drugs that they often test prior to putting them up for sale: “Not a batch of anything goes out from me without it tested by myself. I do not sell anything I don’t use myself. That is my moral standing and anything I sell on here is something I will happily use myself”. [34] Selling drugs is not only a payment transaction, but above all, it is the fulfillment of users’ needs. The latter is presented by vendors as their priority, that is to say that pleasing the customer comes before profits. Quality seems therefore to be a sine qua non condition for transactions: it is implied that sellers will not sell drugs if they are not of a high quality.

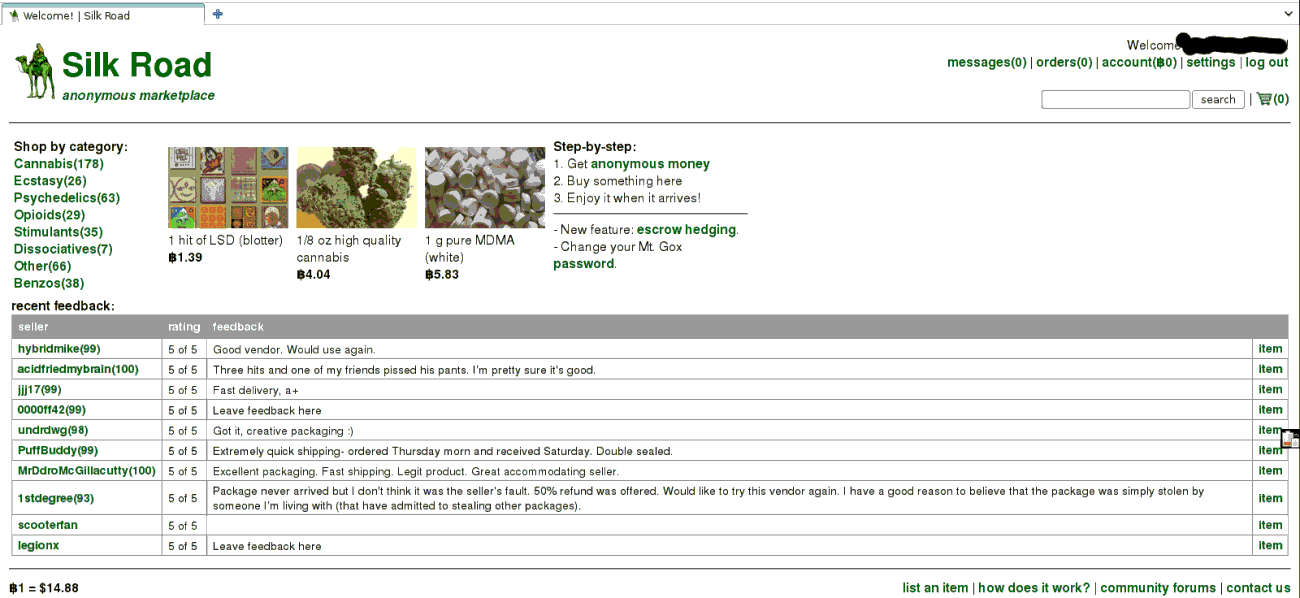

In fine, vendors adopt a “professional approach to running their Silk Road businesses” [35] by adjusting their offer the closest to users’ demand with a high-quality service which is reflected through their reputation. The latter is composed of all feedbacks posted by buyers. It is a way to build trust [36] between sellers and buyers. On the one hand, newcomers have access to the information they need very easily. On the other hand, it is also a way to attract other consumers who might change their supplier. Thus, in order to retain their customers and to get good feedbacks, vendors must please the demand. There are various ways in which the vendor can improve his offer to please customers such as increasing the quantity while maintaining the same price or decreasing the turnaround time. However, “the most effective way to build trust,” [37] remains upgrading the quality of the product. This rating system is also a way to regulate and eliminate less efficient sellers. Vendors’ recognized customer service is a way to legitimize their market shares. Providing customer service is a socially recognized and legitimate quality instead of violence.

Feedbacks given by sellers to one vendor

Moreover, sellers participate in different forums in order to improve the users’ knowledge (quality, quantity and effects). This “harm reduction ethos” [38] – also visible in the willingness to sell only high quality drugs – bolsters the idea that consumers’ rights are the priority and therefore should be upheld.

By resorting to various marketing tools, online drug dealers have managed to reshape the way in which people think about drugs, so that, today, there is a higher risk of people considering drugs as a normal economic good. Therefore, this could make people forget about the illegal nature of drugs as well as the perceived image of dealer because sellers would be considered as normal retailers. Thus, sellers could more easily shelve their drug dealer identity and not be seen as deviants. [39] In the end, sellers transfer their responsibility to consumers by making all information available with regard to the possible effects. It means that the decision to buy and consume drugs rely on individual choices and free will and goes with libertarian ideas. However, this complete dissociation between sellers’ actions and potential negative effects on users may relieve vendors of any responsibility.

Therefore, we may wonder if this new image shaped by vendors and according to which they are not drug dealers but regular retailers, can be maintained over time. Is it possible to maintain a non-criminal and non-deviant identity on the Internet? Is the online identity growing too fast or taking a disproportionate dimension?

Maintaining a non-criminal identity may be easier thanks to the Internet but there is a risk of increasing the separation between online and offline identities

A possible leeway in identity and self-image building thanks to the Internet

The notion of deviance which was popularized in the 1960s – in particular thanks to the work of the Chicago School and the book of Howard Becker [40] – is used to characterize a behavior that circumvents the rules accepted by a society. Three elements are required to define a deviant behavior: the existence of one or several norms, a behavior which infringes this/these norm(s) and a designation process. In the case of drugs, social norms and laws converge as they each define the sale, the purchase and the consumption of drugs, as a deviant behavior. According to Becker, norms are the result of a political process which purpose is to impose one’s norms and then transpose the new norm into the national legislation.

Online vendors underline that their online activities fit in their offline way of life. The choice to sell drugs online is always made in relation to the possibilities offered by their offline life. Indeed, one says “it fitted in with my lifestyle and it was kind of exciting” and another “for me, it was very much the perfect storm. I found myself in a position where I had no job, no local connections and no real change” [41] (implied in offline life). “Labeling” has less impact on them because offline life is seen as a possible escape or answer if they are considered as deviant online. Because they do not dedicate all their time to drug trafficking, they can do everything to avoid a connection between their offline and online life. So, “labeling [which] places the actor in circumstances which make it harder for [the deviant] to continue the normal routines of everyday life and thus provoke him to “abnormal” actions” [42] is less applicable to the online drug dealer who can escape from his online activities whenever he wants.

To express this idea, Suler has theorized the “online disinhibition effect” [43] which is composed of six factors. One of these factors is the “dissociative anonymity.” Thanks to online tools, people can act online without having any impact on their offline life. According to Suler, “in the case of expressed hostilities or other deviant actions, the person can avert responsibility for those behaviors, almost as if superego restrictions and moral cognitive processes have been temporarily suspended from the online psyche.” [44] People do not apply the same moral imperatives online and offline. This is partly due to the distance created by the medium as effects are not visible and vendors do not physically meet with their customers. Because the effects are not in one’s immediate environment, dealing drugs online is less seen as something bad when opposed to the image of the “bad street dealer” who makes profits at the expense of its clients.

Moreover, the Internet structure is under no specific state or institutional control which would have the role of “moral entrepreneur.” [45] The dissemination and enforcement of norms are more difficult to uphold. It may be easier for online vendors to play with the existing domestic norms because they can refer to another national norm corpus to envision their actions as not deviant. The absence of international norm standardization and the complex nature of the Internet (multi-layered, without regulation and applicable laws) are other elements that support this idea of a possible leeway in the process of building a deviant identity.

The Internet (and in particular cryptomarkets) offers the possibility for sellers to avoid being considered as deviant. Indeed, intermediation through technologies enables people to circumvent a criminal identity building.

…showing a greater distance between two identities, two “worlds”

A change in perspective could bring light to other questions raised by the emergence and weight of cryptomarkets.

Using cryptomarkets implies having computer-related knowledge, writing skills or a good customer-service. People who possess this subcultural capital can participate in new activities: there is an adequacy between their skills and actions. Even if cryptomarkets did not exist before and it was unclear whether going on cryptomarkets would be considered as deviant, dealing drug in general was badly connoted.

However, tools available on cryptomarkets have created new opportunities for building a non-deviant and non-criminal identity. This is possible in particular thanks to the anonymization process, the almost impossibility to be caught by law enforcement agencies – people who embody social and lawful norms – the absence of face-to-face contact and the fact that drug is presented as a normal economic good. Therefore, illegal characteristic tends to be shelved as explained above. The error lies in the the perception that vendor have of conducting two completely separated activities. This representation about the Internet and its possibilities – that goes beyond the Dark Net and drug trafficking – are wrongfully perceived as two sides of the same coin: the online world identity and the offline one.

Indeed, even if the identification process is more manageable online, people who act in cyberspace are physically located somewhere. So that they are facing a legal issue – which are the translation from social norms to lawful norms – in countries where drugs or some drugs are illegal. In these countries, even if tools on cryptomarkets enable people to emphasize on some strengths (e.g. customer-service and reputation) valued socially and different from the street dealers’ ones, they cannot escape from the designation process implied by law. Distinguishing the drug dealer from the deviant category in countries where drug is banned stumbled on a conceptual limit. It is nonetheless worth underlining that social norms and the legislation are applicable and valid in a precise space-time. Drugs legalization can occur in the next decades questioning the notion of deviance in relation with drug dealing.

Cryptomarkets have changed the way drugs is perceived, even if the online market represents a minor share of the global trade. Indeed, technical tools enable many protective mechanisms which expand the place dedicated to trafficking. The main innovations lie in Tor and Bitcoin with regard to anonymization which decreases the fear of being caught by authorities. Platforms where drug is being sold provide both sellers and buyers with means to contact each other without previously knowing each other. Therefore, interpersonal and geographical connections are not needed anymore. This disconnect is a way to avoid face-to-face meetings and contributes greatly to the reduction of physical violence. These elements enable a new range of actors who did not have a “deviant career” before, to engage on this market. However, even if they engage in drug dealing, they have managed to partly get rid of the image of the bad dealer. In order to do that, they emphasize on their qualifications such as technical skills or writing skills (useful to handle the customer-service). They also insist on their will to please their consumers’ needs by providing them with high-quality drugs as well as advice on forums. All these factors aim at maintaining a good reputation online which is a prerequisite to keep on selling but also a way to establish their position on the market and to ensure their profits. Thus, they adopt a business approach when selling their luxury products. The distinction process between the online dealer and the « bad street dealer » is based on these qualifications and mechanisms that the bad dealers do not possess. It is worth noting that this distinction is a social distinction. Therefore, cryptomarkets are the mediums of this distinction because they aggregate all tools required to avoid a concordance between street dealers and online vendors. The different possibilities to maintain a non-deviant and non-criminal identity ensue from this distinction and these tools. On cryptomarkets, some ways exist to circumvent norms and their applications. Nonetheless, this estrangement from these identities faces a crucial problem. Online life cannot be totally disregarded: it constitutes an undeniable part of one’s identity whether deviant, criminal or a non deviant. Indeed, the online world is part of the real world.

Carole Cocault

Notes

[25] Munksgaard, R., & Demant, J. (2016). Mixing politics and crime: The prevalence and decline of political discourse on the cryptomarket. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 77–83.

[26] van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Op. cit. p.186.

[27] Goblot, E. (1925) La barrière et le niveau. Étude sociologique sur la bourgeoise française moderne. Presses Universitaires Françaises.

[28] Décary-Hétu, D., Paquet-Clouston, M., & Aldridge, J. (2016). Going international? Risk taking by cryptomarket drug vendors. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, p.70.

[29] Ibid. p.74.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid. p.74.

[32] In order to be able to use finalize early, the vendor must have closed at least 35 transactions in 30 days.

[33] Christin, N. (2013). Op. cit.

[34] van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Op. cit. p.187.

[35] Ibid. p.188.

[36] Cox, J. (2016b). Reputation is everything: the role of ratings, feedback and reviews in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 49–54). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

[37] Tzanetakis, M., Kamphausen, G., Werse, B., & von Laufenberg, R. (2016). Op. cit. p.62.

[38] van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Op. cit. p.186.

[39] Becker, H (1963). Op. cit.

[40] Ibid.

[41] van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Op. cit. p.186.

[42] Becker, H (1963). Op. cit.

[43] Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect, CyberPsychology & Behavior 7(3), pp. 321–326.

[44] Suler, J. (2004). Ibid. p.322.

[45] Becker, H (1963). Op. cit.

Bibliography

Aldridge, J., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2014). Not an ‘‘Ebay for Drugs’’: The cryptomarket ‘‘Silk Road’’ as a paradigm shifting criminal innovation. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2436643

Aldridge, J., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2016). Cryptomarkets and the future of illicit drug markets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 23–30). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Barratt, M. J., Ferris, J. A., & Winstock, A. A. (2016). Safer scoring? Cryptomarkets, threats to safety and interpersonal violence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 24–31.

Becker, H (1963). Outsiders. Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Bitcoin. https://bitcoin.org/en/

Bright, D., & Ritter, A. (2010). Retail price as an outcome measure for the effectiveness of drug law enforcement. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21, 359–363.

Chen, A. (2011, January 6). The underground website where you can buy any drug imaginable, Gawker. Retrieved from http://gawker.com/the-underground-website-where-you-can-buy-any-drug-imag-30818160

Christin, N. (2013). Traveling the Silk Road: A measurement analysis of a large anonymous online marketplace. Paper presented at the International World Wide Web Conference (IW3C2), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Cox, J. (2016a). Staying in the shadows: the use of bitcoin and encryption in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 41–47). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cox, J. (2016b). Reputation is everything: the role of ratings, feedback and reviews in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 49–54). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cox, J. (2016, February 24). Confirmed: Carnegie Mellon University Attacked Tor, Was Subpoenaed By Feds. Motherboard Vice. Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/d7yp5a/carnegie-mellon-university-attacked-tor-was-subpoenaed-by-feds

Décary-Hétu, D., Paquet-Clouston, M., & Aldridge, J. (2016). Going international? Risk taking by cryptomarket drug vendors. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 69–76.

Dörrlamm, M. (2008). Drogenhandel zwischen Mythos und Alltag in der Frankfurter Straßenszene. In Drogenmärkte. Strukturen und Szenen des Kleinhandels. C.H. Beck. Frankfurt am Main. pp. 253-273.

Dredge, S. (2013, November 5). What is Tor? A Beginner’s Guide To The Privacy Tool. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/05/tor-beginners-guide-nsa-browser

Epstein, E.J.. (2017). How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft. Knopf.

Goblot, E. (1925) La barrière et le niveau. Étude sociologique sur la bourgeoise française moderne. Presses Universitaires Françaises.

Greenberg, A. (2013, August 14). An Interview With A Digital Drug Lord: the Silk Road’s Dread Pirate Roberts (Q&A). Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2013/08/14/an-interview-with-a-digital-drug-lord-the-silk-roads-dread-pirate-roberts-qa/#106760565732

Khazan, O. (2013, January 16). The Creepy, Long-Standing Practice of Undersea Cable Tapping. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/07/the-creepy-long-standing-practice-of-undersea-cable-tapping/277855/

Lavorgna A (2016). How the use of the internet is affecting drug trafficking practices. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Munksgaard, R., & Demant, J. (2016). Mixing politics and crime: The prevalence and decline of political discourse on the cryptomarket. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 77–83.

Snowden, E. (2013). “Tor Stinks” Presentation. Retrieved from https://edwardsnowden.com/docs/doc/tor-stinks-presentation.pdf

Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect, CyberPsychology & Behavior 7(3), pp. 321–326.

van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Responsible vendors, intelligent consumers: Silk Road, the online revolution in drug trading. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 183–189.

Thornton, Sarah. 1995. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Tor Project. https://www.torproject.org

Tzanetakis, M., Kamphausen, G., Werse, B., & von Laufenberg, R. (2016). The transparency paradox. Building trust, resolving disputes and optimising logistics on conventional and online drugs markets. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 58–68.

1 Comment