Cryptomarkets are a new phenomenon which gained visibility following a progressive mediatisation, started by the article “The Underground Website Where You Can Buy Any Drug Imaginable” written by Adrian Chen and published on Gawker. [1] Later on, the actions taken by law enforcement agencies, especially American ones, brought to light the growing trend of people doing business online. At the beginning, only a few people knew of the existence of websites located on the Dark Net where it was quite easy to sell and buy drugs.

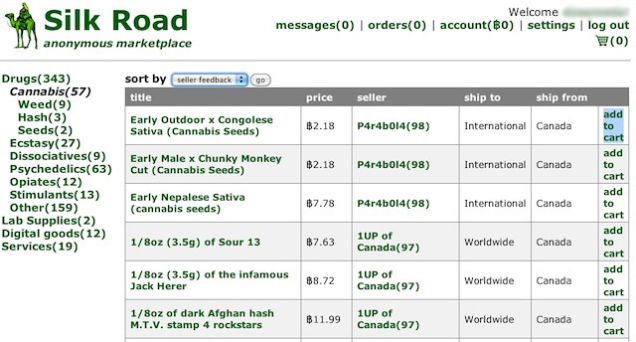

Drugs available on Silk Road

The people who were familiar with those websites had or gained skills in the technological sector. They sometimes shared a similar libertarian ethos which triggered the development of online communities. The law enforcement agencies were aware of websites e.g. Tor which was originally created by the American Office of Naval Research and further developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), with the help of Electronic Frontier Foundation, Knight Foundation and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency [2]. These agencies wanted and still want to limit and, if possible, annihilate the drug trade on cryptomarkets. The legacy of the “War on Drugs” still permeates the methods chosen to curtail online trafficking: in the different operations they launched, agencies systematically shut down all the platforms. In a short-term perspective, these operations are a success because all transactions are blocked, de facto reducing online activity. On the contrary, in a long-term perspective, these operations could be described as a moderate success for law enforcement agencies because their actions contribute to the development of other, far more numerous websites. These new websites take advantage of the re-building process to reshape and strengthen the security protocol, ensuring a better anonymization for users. During the shutdowns, the increase in media coverage makes the cryptomarkets even more famous and popular which suggests that measures taken by law enforcement agencies are, in the end, counterproductive. Indeed, the number of people going on those websites has grown significantly since 2011, when Silk Road – an online platform where it is possible to buy drugs – was first created. [3] The amount of drugs exchanged on these websites has also constantly increased, due to the number of people on these markets (and of course the possibilities they offer). This process can be exemplified by the take down of Silk Road on 2nd October 2013 by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the arrest of Ross William Ulbricht who was suspected of being the founder of the website, under the pseudonym “Dread Pirate Roberts”. After this operation, other websites emerged and replaced the original cryptomarkets such as Atlantis or Silk Road 2.0 which was again shut down a year later. This mechanism is the same, every time a cryptomarket shuts down. People who were not familiar with this « milieu » became more aware of the possibilities cryptomarkets offer, such as an ever expanding number of vendors and buyers. In addition to that, the revelations made by Edward Snowden played a significant role in raising people’s awareness about the importance of anonymity-protecting networks such as Tor. Although cryptomarkets represent a new trend, their development was a very fast one, notably thanks to their characteristics which provide new possibilities in terms of freedom, privacy and business.

Plenty of reasons can explain the interest of people towards the Dark Net: some of them decided to go on cryptomarkets to sell drugs and make a profit. Selling on cryptomarkets implies having a set of skills in order to fulfill all the requirements necessary to preserve complete anonymity. Some people have taught themselves, using the resources available on the Open Web, where there are plenty of forums describing the entire process, while others had already developed the needed skills to sell on the Dark Net. People who decide to sell online are predominantly men in their 20s or 30s: most of them have some sort of qualification and/or employment. Their profiles, their practices and how they present themselves differ from the typical drug dealer image, often embodied by the myth of the “bösen Dealer.” [4] The « bad dealer » can be described as follows: “Ihm wird reines Gewinnstreben auf Kosten der Gesundheit seiner Kundschaft und über die sozialen Kosten, die Abhängigkeit produziert, auf Kosten der ganzen Gesellschaft unterstellt. … Er ist die Verkörperung des Bösen, das im moralisch verwerflichen Handel mit illegalen Drogen gesehen wird. Dass er damit neoliberalen Bildern von aufstrebendem Unternehmertum entspricht und sein Gewinnstreben sich kaum von dem in anderen Zweigen der Ökonomie unterscheidet, wird ignoriert.” [5] Online vendors try to distance themselves from this image which is detrimental to their business. To do so, they rely on technologies which act as an intermediary between them and the drug trafficking “milieu »; this intermediation introduces a physical distance. Therefore, it may be easier for them to distance themselves from the figure of the deviant drug dealer: [6] this negative perception may have less impact on their identity building and self-image. However, the illegal nature of trading drugs casts doubt on the possibility of maintaining a non-criminal identity in society.

Due to the structure of cryptomarkets, vendors feel more confident selling drugs thanks to the pervasive impression of relative safety

Cryptomarkets are held as a much safer environment in comparison to offline drug markets, for both sellers and buyers, due to their specific structure. For this discussion, the perspective of the sellers will be the only one taken into account.

Cryptomarkets have been defined based on the example of Silk Road which used to be one of the biggest cryptomarkets in the world. Cryptomarkets rely on four main characteristics: “It provides drug dealers with (1) a worldwide market for their products, (2) the capacity to sell to customers not already known to them, (3) the ability to trade anonymously and (4) in a relatively low risk environment.” [7] Cryptomarkets are in fact worldwide markets: sellers and buyers from all over the world are connected and can trade between themselves. However, it is important to mention that some domestic markets are more dynamic than others such as the American market and some sellers prefer to focus on domestic markets to reduce their exposure to international scrutiny. In general, sellers and buyers have the same access to information. There is an exception with the private listings on some websites such as Silk Road which are used for bulk transactions. [8]

Less chance of being caught by law enforcement agencies

The ability to trade anonymously relies on peer-to-peer encryption. This encryption is enabled through softwares such as Tor [9] and cryptocurrencies e.g. Bitcoin [10]. Thanks to these mechanisms, people have less chance of being arrested by law enforcement agencies.

Tor – The Onion Router – has been active since 2002 and aims at ensuring privacy and anonymity online. It has sometimes been decried because it can be used to promote illegal activities such as child pornography and arms trafficking which tend to overshadow the beneficial aspects of this software. Some governments strongly oppose the continued existence of this website because its control is difficult and onerous. Tor has been linked to the emergence of ideas and political movements which call into question the political and economic status quo (Snowden, China, Irak and the Arab Spring). Indeed, Tor “offers a technology that bounces internet users’ and websites’ traffic through “relays” run by thousands of volunteers around the world, making it extremely hard for anyone to identify the source of the information or the location of the user.” [11]

It is highly problematic for law enforcement agencies to sue everyone who has sold or bought drugs online: the de-anonymization of all cryptomarket users is theoretically possible but impossible in practice considering current capabilities in terms of time and means. Among the documents from the National Security Agency (NSA) leaked by Edward Snowden [12] in 2013, one revealed the policy adopted by the intelligence agency concerning Tor accounts. In a presentation called ‘Tor Stinks’, the NSA announced that they “will never be able to de-anonymize all Tor users all the time. With manual analysis we can de-anonymize a very small fraction of Tor users, however, no success de-anonymizing a user in response to a TOPI request/on demand.” [13] Therefore, even if the NSA can gather some of the users’ information by exploiting “nodes” and tapping submarine cables [14], the information gathered does not encompass all Tor users and even less Tor users surfing on cryptomarkets (the NSA also relies on its partners from the “Five Eyes” [15] alliance). Therefore, drug vendors on cryptomarkets, even though they are more likely to be targeted by law enforcement agencies, face limited risks, especially if they stick to selling small amounts of drugs and do not make any mistake while anonymizing their personal data.

In addition to Tor, most cryptomarkets use cryptocurrencies, particularly Bitcoin [16], a currency created by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 and made public a year later. The combination of Tor and Bitcoin became a significant key for online anonymization and was one of the main reasons why Silk Road was so widespread and appreciated, according to Dread Pirate Roberts. [17]

According to sellers [18], the risk with Bitcoin lies in its high volatility, even if hedging mechanisms exist to limit the fluctuations of Bitcoin.[19] Some potential sellers might turn away from cryptomarkets, fearing a depreciation of the currency during the transaction, since payment is not always simultaneous with the conclusion of a deal, for instance if “centralized escrow” method is used. In that case, payment is transferred to the seller by a third party, only when the buyer has confirmed that he has received the shipment. [20] For the seller, it is beneficial to use “finalize early” method in a short-term perspective because the incurred risk of an exit scam is reduced and so is the risk of fluctuating cryptocurrencies. However, the fluctuation of cryptocurrencies can also benefit the seller: here, the same logic applies as it does to actions and obligations in the economic sphere.

Therefore, thanks to the structure of cryptomarkets, people who engage in trading online are not at great risk of being caught, except if a sudden change occurs in the political agenda of some states or if an international agreement is negotiated which is highly unlikely (it usually takes years if not decades to reach such an agreement). In case of such drastic upheavals, the communities which control Tor and Bitcoin upgrade the technologies responsible for the anonymizing process, creating a circle between law enforcement agencies which shut down the websites and the creation of new websites even more effective.

Price, shipment for cannabis sorted by seller feedback

The likelihood of incurring serious risks is thus reduced

Through the anonymization of their data, people are less likely to be the victim of violence because nobody knows who they are and where they live, that is, if they do not choose an alias or disclose information as long as they do not provide clues to their real identity. In short, cryptomarkets are characterized by their relatively low risk settings (4). Some users, confident in the guarantee of safety, venture on cryptomarkets while they might be reluctant to sell offline.

First and foremost, every piece of information is available online – including the seller’s and buyer’s reputation. Sellers and buyers agree before the transaction takes places: the space for negotiation afterwards and ensuing conflicts is quite limited.

Moreover, sellers and buyers are less afraid to take part in a transaction because the the exchange is guaranteed by the participation of a third party. For instance, with centralized escrow, arbitration between stakeholders is based on their transaction history and their comments. [21] Thus, the probability of being cheated if one respects the terms of contact is limited with centralized escrow.

Furthermore, the option of resorting to violence is not readily available because of the absence of face-to-face and interpersonal contacts. Sellers and buyers are only in contact through the online platform which serves as an intermediary. This intermediation lowers the likelihood of violence because it hinders the possibility of pressuring someone during the deal. Indeed, offline, violence is used to defend or conquer market shares. [22] The reduction of violence is also linked to the “different set of skills which is required of cryptomarkets vendors to succeed (e.g., good customer service, writing skills) compared with conventional dealers who can utilise physical intimidation to maintain market share (Aldridge & Décary-Hétu, 2014). Cryptomarket vendors may, therefore, arise from a rather different population than street market dealers, who Andreas and Wallman (2009) describe as resorting to violence for dispute resolution due to violence being more normative and a lack of alternative options.” [23] Online vendors do not possess the same “subcultural capital” [24]: they do not and probably cannot resort to violence, shying away from physical confrontation. Hence, they have an interest in underlining the other skills they have acquired to distinguish themselves from « violent » dealers.

Here is part II

Carole Cocault

Notes

[1] Chen, A. (2011, January 6). The underground website where you can buy any drug imaginable, Gawker. Retrieved from http://gawker.com/the-underground-website-where-you-can-buy-any-drug-imag-30818160

[2] Dredge, S. (2013, November 5). What is Tor? A Beginner’s Guide To The Privacy Tool. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/05/tor-beginners-guide-nsa-browser

[3] Christin, N. (2013). Traveling the Silk Road: A measurement analysis of a large anonymous online marketplace. Paper presented at the International World Wide Web Conference (IW3C2), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

[4]Dörrlamm, M. (2008). Drogenhandel zwischen Mythos und Alltag in der Frankfurter Straßenszene. In Drogenmärkte. Strukturen und Szenen des Kleinhandels. C.H. Beck. Frankfurt am Main. pp. 256-258.

[5] Dörrlamm, M. (2008). Ibid. p. 256

[6] Becker, H (1963). Outsiders. Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

[7]Aldridge, J., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2014). Not an ‘‘Ebay for Drugs’’: The cryptomarket ‘‘Silk Road’’ as a paradigm shifting criminal innovation. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2436643. p.4.

[8] We can exclude the private listings in this work because they do not concern the mechanism which first encourage people to go on cryptomarkets.

[9]Tor Project. https://www.torproject.org

[10]Bitcoin. https://bitcoin.org/en/

[11] Dredge, S. (2013, November 5). Op. cit.

[12] The authenticity of these sources can be questioned and has to do with the status of Edward Snowden. Epstein, E.J.. (2017). How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft. Knopf.

[13] Snowden, E. (2013). “Tor Stinks” Presentation. Retrieved from https://edwardsnowden.com/docs/doc/tor-stinks-presentation.pdf

[14] Khazan, O. (2013, January 16). The Creepy, Long-Standing Practice of Undersea Cable Tapping. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/07/the-creepy-long-standing-practice-of-undersea-cable-tapping/277855/

[15] The alliance “Five Eyes”, initially secret, was created in 1947 between the United Kingdom, the USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. It pursues a cooperation between secret agencies in order to gather and share intelligence.

[16] Cox, J. (2016a). Staying in the shadows: the use of bitcoin and encryption in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 41–47). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

[17] Greenberg, A. (2013, August 14). An Interview With A Digital Drug Lord: the Silk Road’s Dread Pirate Roberts (Q&A). Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2013/08/14/an-interview-with-a-digital-drug-lord-the-silk-roads-dread-pirate-roberts-qa/#106760565732

[18] van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Responsible vendors, intelligent consumers: Silk Road, the online revolution in drug trading. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 183–189.

[19] Christin, N. (2013). Op. cit.

[20] Tzanetakis, M., Kamphausen, G., Werse, B., & von Laufenberg, R. (2016). The transparency paradox. Building trust, resolving disputes and optimising logistics on conventional and online drugs markets. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 58–68.

[21] Tzanetakis, M., Kamphausen, G., Werse, B., & von Laufenberg, R. (2016). Ibid.

[22] Bright, D., & Ritter, A. (2010). Retail price as an outcome measure for the effectiveness of drug law enforcement. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21, 359–363.

[23] Barratt, M. J., Ferris, J. A., & Winstock, A. A. (2016). Safer scoring? Cryptomarkets, threats to safety and interpersonal violence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, p.25.

[24] Thornton, Sarah. 1995. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bibliography

Aldridge, J., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2014). Not an ‘‘Ebay for Drugs’’: The cryptomarket ‘‘Silk Road’’ as a paradigm shifting criminal innovation. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2436643

Aldridge, J., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2016). Cryptomarkets and the future of illicit drug markets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 23–30). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Barratt, M. J., Ferris, J. A., & Winstock, A. A. (2016). Safer scoring? Cryptomarkets, threats to safety and interpersonal violence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 24–31.

Becker, H (1963). Outsiders. Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Bitcoin. https://bitcoin.org/en/

Bright, D., & Ritter, A. (2010). Retail price as an outcome measure for the effectiveness of drug law enforcement. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21, 359–363.

Chen, A. (2011, January 6). The underground website where you can buy any drug imaginable, Gawker. Retrieved from http://gawker.com/the-underground-website-where-you-can-buy-any-drug-imag-30818160

Christin, N. (2013). Traveling the Silk Road: A measurement analysis of a large anonymous online marketplace. Paper presented at the International World Wide Web Conference (IW3C2), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Cox, J. (2016a). Staying in the shadows: the use of bitcoin and encryption in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 41–47). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cox, J. (2016b). Reputation is everything: the role of ratings, feedback and reviews in cryptomarkets. In European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21) (pp. 49–54). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cox, J. (2016, February 24). Confirmed: Carnegie Mellon University Attacked Tor, Was Subpoenaed By Feds. Motherboard Vice. Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/d7yp5a/carnegie-mellon-university-attacked-tor-was-subpoenaed-by-feds

Décary-Hétu, D., Paquet-Clouston, M., & Aldridge, J. (2016). Going international? Risk taking by cryptomarket drug vendors. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 69–76.

Dörrlamm, M. (2008). Drogenhandel zwischen Mythos und Alltag in der Frankfurter Straßenszene. In Drogenmärkte. Strukturen und Szenen des Kleinhandels. C.H. Beck. Frankfurt am Main. pp. 253-273.

Dredge, S. (2013, November 5). What is Tor? A Beginner’s Guide To The Privacy Tool. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/05/tor-beginners-guide-nsa-browser

Epstein, E.J.. (2017). How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft. Knopf.

Goblot, E. (1925) La barrière et le niveau. Étude sociologique sur la bourgeoise française moderne. Presses Universitaires Françaises.

Greenberg, A. (2013, August 14). An Interview With A Digital Drug Lord: the Silk Road’s Dread Pirate Roberts (Q&A). Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2013/08/14/an-interview-with-a-digital-drug-lord-the-silk-roads-dread-pirate-roberts-qa/#106760565732

Khazan, O. (2013, January 16). The Creepy, Long-Standing Practice of Undersea Cable Tapping. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/07/the-creepy-long-standing-practice-of-undersea-cable-tapping/277855/

Lavorgna A (2016). How the use of the internet is affecting drug trafficking practices. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Ed.), The Internet and Drug Markets (EMCDDA Insights 21). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Munksgaard, R., & Demant, J. (2016). Mixing politics and crime: The prevalence and decline of political discourse on the cryptomarket. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 77–83.

Snowden, E. (2013). “Tor Stinks” Presentation. Retrieved from https://edwardsnowden.com/docs/doc/tor-stinks-presentation.pdf

Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect, CyberPsychology & Behavior 7(3), pp. 321–326.

van Hout, M. C., & Bingham, T. (2014). Responsible vendors, intelligent consumers: Silk Road, the online revolution in drug trading. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 183–189.

Thornton, Sarah. 1995. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Tor Project. https://www.torproject.org

Tzanetakis, M., Kamphausen, G., Werse, B., & von Laufenberg, R. (2016). The transparency paradox. Building trust, resolving disputes and optimising logistics on conventional and online drugs markets. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 58–68.

No Comment