Very few countries have not been built around sea routes and harbours, seemingly infinite sources of international trade and national increase of wealth. However, some countries without any waterfronts have developed, thus forming territorial enclaves within entire continents. This is the case of Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda. Regrouped by the commonly accepted expression of Great Lakes Region, these central-eastern African territories, far from seas and oceans, are described as “inter-lacustrine”. Put together by this relatively abstract geographical structuration, these territories “between the lakes” – although collective imagination may sometimes fantasise this geographical construction -are lands with extremely complex geopolitical situations.

The geographical area of these territorial enclaves in East Africa is thus revolving around these Great African Lakes that have permeated the tales of 19th-century colonial explorers, an epoch which also has given the lakes their names. “Great” is a euphemism to describe the lakes Kyoga, Albert, Edward, Kivu, Tanganyika, and Victoria, to name just the major ones. Indeed, more than 68.000 km² wide, Lake Victoria is the second largest freshwater lake in the world. As for Lake Tanganyika, it is the second deepest lake after the Baikal in Siberia. But these superlatives only hide the geographical, political, and economic situation of the countries whose sole waterfronts are these lakes. Although one could imagine some sort of river passage that would connect these great lakes to the Indian Ocean, this is not the case, as most riverbeds here cannot be navigated and cannot ensure a stable inland navigation so that commerce becomes possible.

The Great Lakes Region thus faces the question of “opening up”, a question that gains weight with globalisation taking over the world and forcing everyone to take part whatever the cost. Moreover, this question is afflicted – if one skips the entire colonial period – by decades of bloody conflicts, sometimes genocidal and cataclysmic for the waterside populations of the Great Lakes of East Africa. Opening up these States, both politically and economically, is thus a lengthy and pluri-scalar process, one that seems to refuse take-off despite the relative decrease in conflicts and massacres.

So that we can better understand this question of “opening up” in the Great Lakes Region, one has to try and understand the political and military situations, the social and geographical situations, but also interrogate the international logics in such a region.

The open wounds of the 1990’s

The reconstruction of the Great Lakes Region from the 1960’s onwards was defined by violent conflicts in the entire region. So many wars, massacres, confrontations, in a region which borders do not seem to stabilise perfectly on the colonial outlines, go through the last few decades that it would be vain to tray and analyse them all, to try and dissect each one of them to have a better grasp of the current geopolitical situation. From the repression of Idi Amin Dada between 1971 and 1979 to the Ugandan-Tanzanian wars of “liberation”, from wars in the Congo in the 1990’s to the Burundian civil war and the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the Great Lakes region is the subject of conflicts so violent and so massive that the peace objectives of international observers seem completely utopian. Although several peace agreements – the most famous of which are the Arusha agreements of 1993 and 2000 – have allowed some clashes to come to an end in Rwanda and Burundi, conflicts did not end at the turn of the century. Likewise, despite his rise to power in 1986 – and still in position to this day – the Uganda president Yoweri Museveni cannot pretend to have secured perfect peace in a country that still suffers from decades of murderous post-colonial dictatorship. These innumerable conflicts thus create a “logic of security above all” in these enclaved territories, which traumas and systemic instabilities still define institutional and political life.

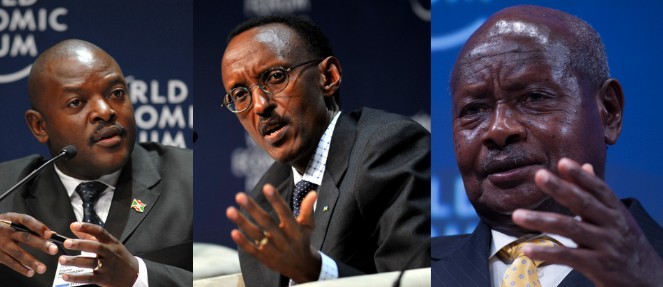

Museveni, Kagame, Nkurunziza – durability, stability, democracy?

What thus defines these war-torn regions, whether civil wars, liberation wars or brutal dictatorships, is paradoxically a form of institutional stability, if not genuine then theoretical. Indeed, Ugandan, Rwandan, and Burundian presidents have respectively been in power for 34, 20 and 14 years now.

Nonetheless, this presidential continuity is obviously not representative of the political and military stability in any of the three States. Museveni’s presidency, one of the longest in the world with his Cameroonian and Equatoguinean counterparts, is yet not a peaceful one. Opposed for example to the Lord’s Resistance Army in the north between 1988 and 2006, a conflict which has killed tens of thousands in Uganda but which is continuing in South-Sudan and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Museveni is yet still seen by many, especially other African leaders, as a guarantor of peace in the continent. An ironic feature when one knows that Museveni has increased the security budget from 260 to 480 millions of dollars between 2010 and 2016, ensuring thus a sensible wage increase for the police forces, a pay rise which goes hand in hand with infallible loyalty.

As for Paul Kagame, close to Museveni in 1986 when they liberated Uganda, he rises to power in 2000, after years at the very “incriminating” Defence minister position. Indeed, Kagame takes part in the rebellion in Zaire with Kabila against Mobutu with his former “mentor”, then in the Second Congo War a few years later against the Kabila regime. His presidency, which still tries to overcome the 1994 genocide, is yet acknowledged by many as having put an end to the armed conflicts. On the other hand, Kagame is criticised from every direction for his failure to uphold basic democratic principles – freedom of speech, of the press, multi-party system, etc. – and for having amended the constitution so that he could run for president several other times, amendments that could keep him in power until 2034.

When it comes to Burundi, the youngest of the Great Lakes Region’s leaders, Pierre Nkurunziza (deceased on June 8th, 2020, of a heart attack) seemed to complete the self-evidence that are long African presidencies. In power after the elections and the negotiations that followed the Burundian civil war, Nkurunziza does not venture into outside wars like his counterparts but nonetheless encapsulates criticisms on the democratic features of his party and his government during elections. Target of an attempted coup in 2015 after his second re-election, which was deemed unconstitutional, Nkurunziza then unleashes repression against the opposition, both on Burundian soil and in exile. His intransigence towards those he calls “putschists” without any nuance is firmly condemned by international organisations from which his power yet depends. Indeed, European authorities suspended more than 400 million euros of help, plunging the country in a dangerous financial situation.

The political and institutional settings of the Great Lakes Region are crucial to understand the efforts to open up these countries which economies have trouble weighing in the international economic system. The different governments seem more concerned by the management of their territories on a national scale than pushing for more cooperation between State to manage these inter-lacustrine territories that pay no heed to administrative borders.

Agriculture, fishing, dams – the obvious features of the Great Lakes?

Although the State actors are separated by precise administrative borders, the Great Lakes of East Africa do not make such a united picture when it comes to their resources and their wealth. If the idea of a region subject to heavy rainfall may be persistent in our perception of the Great Lakes Region, this perception does not equate to a thriving agriculture everywhere on these territories. Indeed, although 80% of the region’s population works in the agricultural sector, the latter only amounts to 30% of the GDP of the Great Lakes countries, an imbalance that can be explained by the difficulties in exporting these agricultural resources abroad. Indeed, a large proportion of the products harvested have to reach their final selling point within 24 hours. Without a true economic cooperation between the States, opening up the region for the population to benefit is impossible.

As for the halieutic resources of the Great Lakes – although very large – they are also disputed in the region. In spite of their great fish reserves, the Lakes also suffer from human-induced problems, whether it be pollution or the upsetting of ecosystems, most notably the introduction of the Nile perch which caused the extinction of several dozens of local species and reduced the size of the fishermen’s catches. These interferences in the fish biomass have forced several factories to shut down, thus increasing the prices on a local scale, all the while constantly increasing transportation costs, fragilizing the economic and social situation of the populations around the lakes. Although this economic sector represents no more than 5% of the neighbouring countries’ GDP, the life of more than 5 million people directly depends on fishing. And of these lakes, it is of course Lake Victoria – which territorial sovereignty is shared between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania – that has a predominant position with 46% of the Ugandan national fishing resources. However, the conflicts and political tensions previously mentioned also play a role in this sector, preventing the development of efficient measures in terms of regional cooperation to ameliorate fishing, environmental, and exportation structures, which would allow the local populations to be economically less marginalised. Projects like the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project (LVEMP) have seen the light of the day since 1994, but, as they are under the tutelage of national ministries, they suffer from the evolutions of the various political and geopolitical events.

As for the dams, logical use of such massive hydraulic resources, they represent a more than important share of the energy production of the Great Lakes countries (90% of the Ugandan energy comes from dams).

Ore – the shady spots of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes’ wealth, however, goes beyond the water resources. Indeed, the minerals also play a crucial part in the economic and political development of this region. Tin, tantalum, tungsten, platinum, palladium – these ores are now genuine economic pillars, which wealth cannot be measured. Essential to the building of electronic devices of all sorts, these ores provide countries like Rwanda and Burundi with a heavy access to the international market. 1.200.000 digging craftsmen, for approximately 20% of the world production of tantalum happen to be working in the Great Lakes region. But, just like the infamous blood diamonds, the ores of the Great Lakes quickly became conflict ores. Indeed, the major part of these mineral resources, keystones of the international economy, happen to be on conflict-ridden territories, most particularly the Kivu region in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where armed groups of various allegiances control the entire distribution chain, thus preventing any social or economic development for the African workers. And yet, despite a few NGOs and non-African governments’ attempts to demand the ore be certified, the commercial emergencies have dominated the debate, the economic demands for tantalum & co. being to powerful for labour conditions to improve and human exploitation to stop in the region. China, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, etc. – all depend on these ores, thus losing any leverage on this local economy.

From these complex political, economic, and environmental situations ensues a real need to open up the Great Lakes region. From the simple geographical fantasy of these States, concrete ideas and projects were thought of to relieve a region that suffers from the lack of waterfront.

East Africa’s corridors

The first of said fantasies is that of a true physical disenclaving, i.e. developing a strong infrastructural network so that Kampala, Kigali, and Bujumbura can be connected to the Kenyan and Tanzanian waterfronts. This infrastructure takes the shape of a transportation corridor, that is a “multimodal structure made up of roads, railroads and airline connections, thus providing an efficient economic junction between economic centres of one or more isolated zones of one or more countries and countries with waterfronts”. Crucial stake for insertion and stability within the international market, these corridors quickly become subjects of massive investments and of discussion at every administrative level. To this day, three corridors play a major role for the opening up of the region: the Northern corridor (connecting Kampala and Mombasa), the Central corridor (connecting Dar es Salaam to Kigoma) and the Southern corridor (connecting Dar es Salaam to Lusaka). These three corridors thus provide the isolated countries, as well as regions (the south of Ethiopia and of South Sudan, the East of the DRC) with better access to commercial markets, allow them to sensibly modify their imports and exports’ policies. Thanks to these corridors, the commerce between Great Lakes countries has doubled between 2005 and 2010 and commercial partnerships between the isolated countries as well as with Kenya and Tanzania have been reinforced.

However, these infrastructural efforts have been met by a plethora of difficulties, greatly compromising the hopes to open up the region. Firs of all, despite the increase in commercial exchanges, poverty levels have risen: 38% of the region’s population is now living under the poverty line as of 2010. Then, the logistical performances of such corridors are actually quite poor, creating massive additional fees on every part of the roads and railroads. This also goes hand in hand with the oversaturation of harbour sites – more specifically in Mombasa & Dar es Salaam – which forces coastal countries to use these sites as storage places and to keep numerous ships standing about, costing the enclaves even more. Loss of time, loss of money, but also increase in non-tariff barriers (informal roadblocks, lack of border procedures’ harmonisation) contribute to the mediocre opening up of the Great Lakes countries. And on top of it all, the weakness of supranational cooperation has led to decisional processes which exclude enclaved countries, deepening their economic and political dependence of their neighbours.

International cooperation

If it seems obvious that tariff agreements and regional institutional reinforcement would be solutions to these many issues, one may not conclude that these ideas have not been worked on and put forward. Beyond the African Union, it is the East African Community (EAC) that will try to assume the position of supranational organisation, responsible amongst other things for the opening up of the Great Lakes region. Founded in 1967, and then dissolved in 1977 because of numerous political difficulties, this organisation is recreated in 1996, its treaty ratified and in effect 4 years later. With internal liberalisation, regional cooperation, harmonisation, progressive disengaging of States as objectives, this organisation persistently shows institutional weaknesses against public and national powers that refuse any loss of sovereignty and against conflicts throughout the region.

The Great Lakes Region International Conference (GLRIC) as well as the Great Lakes Countries’ Economic Community (GLCEC) have also been established to contribute to this long-wanted economic take-off. Negotiated between 2000 and 2006, the GLRIC gave birth to a Pact on Security, Stability and Development in the Great Lakes Region which was signed by a large number of African heads of State (Angola, Central African Republic, Zambia etc.) on top of the concerned States. Many projects, of reinforcement and doubling of the corridors but also of renovating the hydroelectric power plants, of prevention against food insecurity have seen the light of day and are currently being studied. However, these projects globally lack stability, as much financially as politically, and the results are still awaited.

International investments, more specifically from the World Bank and the European Union but also from bilateral partners such as the United States, the United Kingdom or Belgium, also play a crucial role in these policies, which oscillate between political stability and economic opening. In the case of the corridors, hundreds of millions of dollars have been given by the World Bank and the European Union so that entire portions of roads could be rehabilitated and built.

Unsurprisingly enough, it is the security sector that benefits the most from international cooperation. Security system reform (SSR), MDRP (Multi-Country Demobilization and Reintegration Program) or TDRP (Transitional Demobilization and Reintegration Program), these acronyms point to stabilisation projects in the region, financed by the States themselves but also by international organisations. Since “the idea that security is the primary condition to foster economic development” still prevails in international negotiations and diverse national policies, it is not surprising to see millions of dollars invested to that end. Demobilisation of hundreds of thousands of soldiers (and child soldiers) and their reinsertion in society is of course a priority for the Great Lakes region, a choice that downgrades any quick opening up policy.

* * *

To thoroughly assess the opening up efforts in the Great Lakes Region would be impossible. The region – of immense natural and human wealth, of often unexploited if not neglected potential – has been struck by many political and military crises, minor and major, for decades. Cooperation, development and thus opening up projects are numerous and good-willed but go through seemingly unsurmountable institutional weaknesses and constraints that only give mitigated results. On top of these political crises that never cease to hit every State, the worldwide environmental crisis is certainly going to endanger the natural resources of the region on which the population relies for survival.

Florian Mattern

Sources

- Carrière, Pierre « Grands Lacs Africains », Encyclopaedia Universalis, disponible à http://www.universalis-edu.com/encyclopedie/grands-lacs-africains/ en date du 14/04/2020

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre « Introduction. L’Afrique des Grands Lacs, réalité ou mirage géopolitique ? », in Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.) L’invention de l’Afrique des Grands Lacs. Une histoire du XXe siècle, (Editions Karthala, 2010), pp. 5-26.

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre « Des violences qui se donnent la main : vers une explosion ou un nouveau centre de gravité ? », in Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.) L’invention de l’Afrique des Grands Lacs. Une histoire du XXe siècle, (Editions Karthala, 2010), pp 385-402.

- De Putter, Thierry & Delvaux, Charlotte « Certifier les ressources minérales dans la région des Grands Lacs », Politique étrangère 2/1 (2013), pp. 99-112.

- Gahama, Joseph & Lumumba-Kasongo, Tukumbi « Concluding Remarks: Where Do We Go From Here? », in Gahama, Joseph & Lumumba-Kasongo, Tukumbi (eds.) Peace, Security and Post-conflict Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Regions of Africa (Codesria, 2017), pp. 359-366.

- Hache, Emmanuel & Mérigot, Kévin « Géoéconomie des infrastructures portuaires de la route de la soie maritime », Revue Internationale et Stratégique 107/3 (2017), pp. 85-94.

- Léon, Alain « L’Afrique orientale : asymétries sous-régionales et recompositions spatiales » in Hugon, Philippe (ed.) Les économies en développement à l’heure de la régionalisation (Karthala, 2003), pp. 191-210.

- Lott, Gaia « De Abdallah à Museveni : un changement dans la continuité à l’Africaine », Revue internationale des études du développement 235/3 (2018), pp. 179-201.

- Luengo-Cabrera, José & Nuzzo, Luca « Great Lakes – weak democracies? », European Union Institute for Security Studies (2016), pp. 1-4

- Mérino, Mathieu « L’intégration régionale par le bas, force de l’East African Community (EAC) », Géoconomie 58/3 (2011), pp. 133-147.

- Minani Bihuzo, Rigobert « Unfinished Business: a Framework for Peace in the Great Lakes », Africa Center for Strategic Studies 21/1 (2012), pp. 1-8.

- Mwendwa Kaminchia, Sheila « The Déterminants of Trade Costs in the East African Community », Journal of Economic Integration 34/1 (2019), pp. 38-85.

- Patry, Jean-Jacques « Approche comparée des processus RSS dans les Grands Lacs », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est 48/1 (2014), pp. 107-138.

- Porhel, Ronan & Léon, Alain « L’influence des corridors dans le développement régional : le cas de l’East African Community », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est 48/1 (2014), pp. 17-36.

- Porhel, Ronan « Le secteur de la pêche en Afrique de l’Est : un révélateur des ambigüités de l’intégration régionale », Géoéconomie 58/3 (2011), pp. 117-132.

- Révillon, Jérémy « L’Afrique des Grands Lacs, gestion de la poudrière burundaise », Revue Défense Nationale 792/7 (2016), pp. 127-131.

- Sanginga, Pascal., Mulume Mapatano, Sylvain & Niyonkuru, Deogratias « Vers une bonne gouvernance des ressources naturelles dans les sociétés post-conflits : concepts, expériences et leçons des Grands Lacs en Afrique », VertigO – la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 17/1 (2013), pp. 1-21.

- Taithe, Alexandre « Le changement climatique dans la région des Grands Lacs », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est 48/1 (2014), pp. 37-50.

- Wim, Thiery., Davin, Edouard., Panitz, Hans-Jürgen., Demuzere, Matthias., Lhermitte, Stef & van Lipzig, Nicole « The Impac of the African Great Lakes on the Regional Climate », Journal of Climate 28/10 (2015), pp. 4061-4085.

- « La pêche dans les grands lacs d’Afrique de l’Est » in Paugy, Didier., Levêque, Christian., Mouas, Isabelle & Lavoué Sébastien (eds.) Poissons d’Afrique et peuples de l’eau (IRD Editions, 2011), pp. 233-246.

- « Stratégie suisse de coopération pour la région des Grands Lacs 2017-2020 », Direction du développement et de la coopération de la Confédération Suisse, pp. 1-20.

No Comment