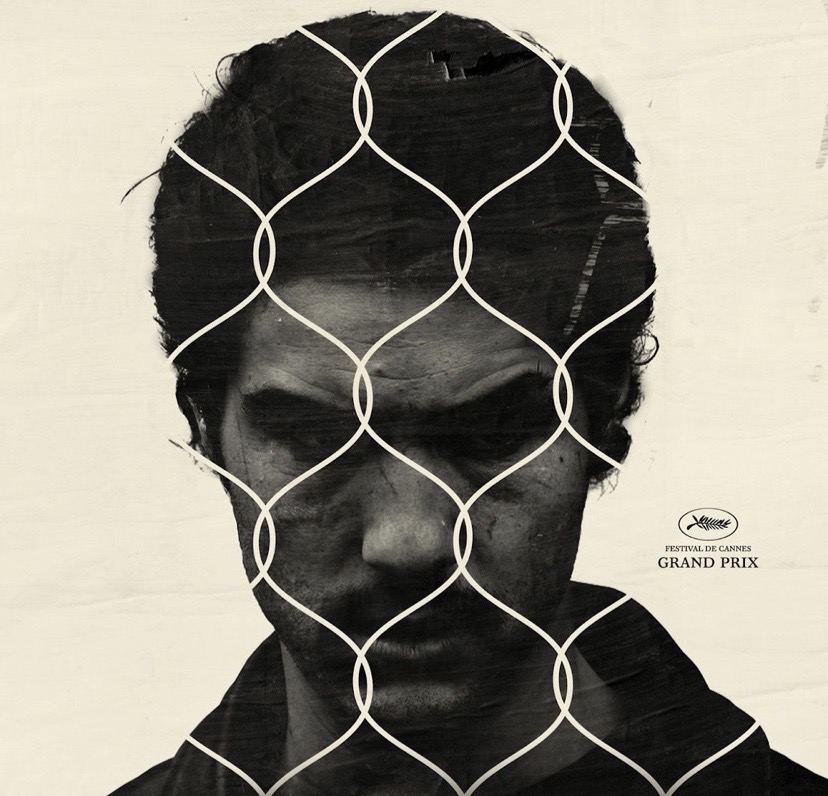

The Privatisation of the Prison System: The Liberal Economy of Suspended Time

What are inmates worth on the market? The privatisation of the prison system in numerous countries has benefitted many multinationals. Cheap workforce, chained consumers, mass incarceration policies were supported by powerful lobbies. Prison time, immigration, parole: the privatisation phenomenon gnaws on the entire correctional system for profit, to the detriment of society’s collective interest. Today Classe Internationale encroaches the topic of carceral privatisation and its impacts on penal policies.

In Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, the mass incarceration phenomenon is dated back to the French Revolution, and more precisely to the 1791 Assembly. “Between crime and a return to right and virtue, prison will be a space between two worlds, a place for individual transformations to take place so that the State can reclaim the subjects it had previously lost.”[1] Before then, prison had a residual position in the hierarchy of sentences: the criminal decree of 1670 had limited its function to lettres de cachet and to the incarceration of wrongful debtors. The change following the French Revolution is sudden and violent, as the Criminal Code’s project presented to the Assembly by Le Peletier can attest, which proposed a panel of punishments, “a theatre of sentences”. In just a few years, detention becomes the punishment’s essential shape, a transformation consecrated by the 1810 Penal Code. At this time, Foucault describes Europe as undergoing a “colonisation of criminality by prisons”. This mutation affects indeed Joseph II’s Holy Empire as much as Catherine II’s Russia, which is given a “new code of laws”. From the Restoration onwards, between 40 and 43.000 inmates are locked up in French prisons, i.e. one inmate for 600 inhabitants.

This monolithic solution is heavily criticised at the time: “So that if I betray my country I get locked up; if I kill my father, I get locked up; every offence imaginable is being punished in the most similar manner. It feels like seeing a doctor for whom every illness is treated the same.”[2]

The requirements of this penal revolution are huge, and the State thus has to rely on private companies known as “les renfermées”. In exchange for a daily fee paid by the State, the company takes care of everything: the “general enterprise” system is installed, although severely criticised. From Tocqueville to Jaillant, everyone is shocked at the insalubrity of places off of which some make money: “The inmate becomes the man… or rather the entrepreneur’s thing… the entrepreneur’s goal is to make money; and the government, by making business with him, has necessarily bent more or less the public interest to the private interest.”. “Up until now, the central houses service has been primarily organised from a financial perspective” writes Jaillant in 1873 during one of Parliament’s Investigative Commission. The Third Republic, and more broadly the first half of the 20th century, have resulted in the handling of the prison system by the public authorities.

The prison system endures the privatisation wave of the 1980’s, victim of the hardening of the penal policies begun under Nixon as early as 1969. This change of tone in the American criminal policy is going to make the number of prisoners skyrocket and challenge the State-run prisons. In the face of this never-ending “War on Drugs” led by the American authorities in the middle of the Reaganian neoliberal boom comes the private solution, the handover of some of the State’s prerogatives to private companies. A machine is then set in motion; a private carceral industry which economic survival relies on the quantity of inmates it can take in its facilities, a number which goes beyond 7 million of individuals under the correctional yoke with more than 2.3 million of inmates and prisoners, all of this only on U.S. soil. The U.S. model is a unique example: 25% of the world’s carceral population is detained in the USA, despite a population representing only 1% of the world’s total population.

Delegating competences to reduce costs, the States’ strategy

The private prison model is very different depending on the country in which it takes place. Approximately 11 countries have undergone some kind of privatisation (mostly Anglo-Saxon, but also Japan, Germany, France or even Chile which became the first South-American country to sign a full contract with penitentiary companies, or even Peru since 2010) of different proportions. If the carceral privatisation phenomenon is affecting the land of the free more than any other country in the world, this phenomenon has nonetheless spread to a dozen more countries including England, Scotland, or Australia. In 2011, the latter two respectively held 17 and 19% of their prisoners in private facilities. In Australia, this percentage may seem important, mainly because it results from a 95% increase between 1998 and 2011.[3]

France has not been spared by this phenomenon either. Indeed, public-private partnerships have been flourishing, especially since February 19th, 2008, when Minister of Justice Rachida Dati signed a contract with Bouygues to deal with the construction, management, and upkeep of three new prisons. The Chancellery pleaded for the reduction of costs, an idea largely criticised by the controller and auditor general in a damning report published in 2010 revealing the generous margins made by the private actors to the inmates’ detriment, as well as the cost of the professional training (7.28€ in public management versus 17.23€ in delegated management).

In the United States, the first private prison was inaugurated in 1984 in Texas. Today, one tenth of the 2.3 million American prisoners are locked up in a privately-run facility. This federal average hides major discrepancies since about twenty States forbid the use of private prisons and that the record is held by New Mexico with 43.1%. In exchange for the construction and the management of the prisons, the government pays “occupation clauses” and commits to using between 80 and 100% of the bed space or be subject to fees. GEO Group and CoreCivic (previously Corrections Corporations of America or CCA) share about 3.5 billion of annual revenue from this market.

In the United Kingdom, the market is in the hands of two large multinational corporations: G4S on the one side, active in 125 countries, with 657.000 employees and with a 6.8 billion pounds turnover in 2014. In 2018, the Ministry of Justice has reclaimed control of the Birmingham prison from private operator G4S after an inspection from the penitentiary services had revealed the “appalling” condition of the 1.200 inmates’ large prison. On the other side is Serco, known as “the largest company you have never heard of”.[4]

The big picture is there: prison has become a promising market to be conquered in many States, although some, particularly Germany, have decided to take a step back. One major problem lies: privatising the prison system goes along with exploitative policies and advocates a disastrous mass incarceration phenomenon.

For-profit policies, the companies’ strategies

The prisoner, an exploited worker in the United States

The idea of work is embedded in the concept of prisoner redemption. The Rasphuis prison in Amsterdam, opened in 1596 and earmarked for beggars and young wrongdoers, had made work mandatory while providing a wage for it. The prison’s aim being reinsertion, idleness, mother of all vices, must be fought and young people learn new skills. However, legal loopholes have allowed the development of nearly free workforce in prisons.

In the United States, the 13th Amendment adopted by Congress on October 6th, 1865, abolished slavery. Yet, a legal void remains, which private interests will not ignore. Indeed, it states that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction”. This legal subtlety has been used as a constitutional basis to exploit prisoners’ work. Thus, the average hourly wage in prison in the United States is $0.63 per hour. This average also hides major discrepancies since prisoners in Texas, Georgia or Alabama are not paid at all, and are even forced to work under threat of disciplinary sanctions. Long time no see, slavery.

And for what kind of work? The majority of inmates are used for maintenance, which allows managing companies to limit their expenses since the working factor’s impact is negligible. However, maintenance is not all they do. Indeed, in California, 11.65% of the State firefighters are prisoners, working a wage of 3 or 4 dollars a day[5]. Twist of fate, these new skills will not be transferable since California’s law forbids firefighters to have criminal records. Residual but not without meaning, some inmates, indebted – one has to know that around 90% of US prisoners have not been sentenced by a judge[6], since not everyone can afford a good attorney and that the prosecutor only investigates at cost, and have thus had to take a side deal with the prosecutor – have joined the entertainment industry as corrida distractions. You get 4 prisoners, one bull, excite the animal: last inmate standing scoops the pot.

Moreover, several public companies use inmates as low-cost workforces. Thus the poultry farming company Kock Foods has been investigated on their use of prisoner labour in Alabama’s poultry industry by the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC) which concluded that in at least seven States, “dozens of poultry companies” have been taking advantage of the carceral workforce. The industry conditions are brutal for all workers in the poultry division. According to federal data, poultry transformation factories such as Ashland have an injury rate nearly twice the national average. Work-related diseases are approximately six times higher than the national average, traumas caused by repetitive stress, respiratory issues due to frequent exposure to chemicals. Since 2015, 167 accidents, including eight deaths and several amputations, have officially been investigated by the federal authorities. In the data collected in Georgia and North Carolina, the SPLC has uncovered that “at least two dozen inmates had been injured since 2015 at work within the poultry sector.”

Better known by the general public, big trademarks like McDonald’s, Walmart or even Victoria’s Secret[8], through their subcontractor Third Generation, had been hiring inmates before a scandal put an end to it. The carceral sector generates approximately 1.5 million dollars in market value for the textile industry[9].

To denounce this exploitation, inmates had begun a strike on August 21st, 2018. However, this protest could only last until September 9th, 2018[10], as inmates are without any union representation to defend their rights since a Supreme Court decision in 1977, “Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union (NCPLU)”.

Detention and consumption, the private prisoner’s shackles

If the privatisation of the carceral system’s initial strategy seems to reflect budgetary policies still in force, it has also opened up a real market, a plethora of economic opportunities which investors have not ignored. Since the first American private prison opened in 1984, companies have developed a particular economic model, specific to the judicial and carceral system in effect. More than 4.000 American companies have thus conquered this new market, infiltrating every branch of the carceral sector in lieu of the State. Although it is obvious these new companies have undertaken the management, construction, and maintenance of classical carceral facilities and privatised the security aspect, carceral privatisation has also monopolised the medical, telecommunications, surveillance sectors but most importantly probation and parole[11].

Although public healthcare in the US has never been remarkable before, the reduced costs ideology, de rigueur in the private sector, has led companies – like Corizon or Wexford – to reduce the personnel but also to bill healthcare even more than what the State already does. Testimonies of abuses by contract doctors and nurses are plenty, on top of the difficulty for inmates to access costly first aid and essentials without any revenue. This is the case of women’s hygienic protections which every inmate has to buy except if she has a doctor’s prescription. The hitch? An appointment with the prison’s on-call doctor is charged as well.

The telecommunications sector, and most particularly telephony, has been invested by companies like JPay or Securus so that phone calls for or by inmates are profitable. Although an average cost would be impossible to determine for the amount of companies involved is so great, it is not uncommon to see the price of these phone calls go beyond a dollar per minute, a high price to pay for low-income families who thus have to struggle each month to afford a regular phone call so as not to lose touch with an imprisoned family member.

Although the word “prison” usually conjures up an image of a cell with bars on the window, most of the carceral system – more than two thirds in the USA – is found outside this picture of a jail. Indeed, the large majority of the correctional system consists of a sort of partial liberty, whether probation or parole. Since keeping 2% of the American population behind bars is an impossible thing to do, private companies have greatly increased the use of probation and paroles – and that since 1976 – all the while making a profit off it. The opportunity to get out early or to avoid imprisonment, which most prosecutors defend to avoid trial or when bail is too high, most particularly for misdemeanours (traffic violation, shoplifting, public intoxication), then becomes an economic burden for inmates. Companies are indeed allowed to declare numerous charges and mandatory fees to the convicts, whether it be supervision costs, alcohol, and drug tests, etc. Default to pay, needless to say, automatically means a return to prison for the inmate on probation, which forces him to do whatever it takes to pay these fees, fees which prices can be set arbitrarily.

However, the “economic success” of probation for the private sector also relies on the rapid development of inmate surveillance methods, i.e. the use of ankle bracelets so that convicts are permanently geotagged. If such a method has been around since the 1960’s, it has quickly become a keystone of the carceral privatisation phenomenon’s functioning, its use thus increasing from more than 65% between 1998 and 2015, generating more than 300 million dollars a year for the companies that chose this technology. And since 2009, 49 States (except Hawaii) allow the private companies to charge the price of the bracelet to the inmate. Though the idea of GPS devices as alternatives to carceral overpopulation or simply as an alternative for misdemeanours may seem interesting, its results, beyond the more than questionable financial logic, are mitigated at best. A very high number of alarms set off by these devices – more than 70% in a 2007 Arizona study – turn out to be false alarms triggered by dead zones and have thus led to a degree of permissiveness from parole officers, along with a higher violation rate. These surveillance devices are also known for heavy malfunctions that cause inmates daily physical pains (burns, abrasions, infections, swellings, headaches, etc.) as well as having a very heavy socially stigmatising side effect, the image of the hardened criminal deeply enmeshed in our minds seeing the size of such an object. According to Erving Goffman, “stigmas” are understood as physical traits or features likely to discredit those it concerns.[12]

The combination of all of these corporate strategies has been described as the “McDonaldization”[13] of private prisons, a perpetual search for low costs and immediate profits to the detriment of the just supervision of inmates and personnel working conditions. The prisoner is thus imprisoned in an insidious consumption system that fights any attempts at reinsertion, favouring repeated offences and a global increase of criminality.

The private carceral sector, a market of political influence

Immigration and privatisation, locking up foreigners for profit

When one discusses the private carceral sector, one too often forgets that penalising immigration requires detention centres to be built. Here again, private interests emerge along with an enormous growth potential, which prison multinationals quickly seized.

According to Louise Tassin, Europe is developing a “market to imprison foreigners”[14]. Indeed, the incarceration of migrants in Italy is run by French company GEPSA (which runs 16 prisons and sells her services to 10 administrative retention centres in France). The GDF Suez subsidiary Cofely has invested in identification and expulsion centres and has collected rent from the State in exchange for its work. To earn more market shares, GEPSA has been applying a price competition policy, to the detriment of refugees.

In the United Kingdom, the market is dominated by a handful of security multinationals, sharing 73% of the migrants held by the Immigration and Customs Services, as well as most of the centres. The sector’s privatisation had begun in the 1970’s under Edward Heath’s conservative government, and in 2015, only 2 IRCs (Immigration Removal Centres, where migrants can be locked up indefinitely) were run by Her Majesty’s Prison Service. Every other IRC is split between G4S, GEO Group, Serco, Mittie and Tascor. The average annual cost of detention is £94.56 per person per day. Very criticised, the detention apparatus of British migrants is renowned for its utter disrespect of detainees’ rights. In total, the Home Office has signed contracts worth more than 780 million pounds for the detention and expulsion of migrants (2004-2022).

The Nordic countries (like Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden) are known for their generosity towards asylum seekers but have also privatised a great deal of services for asylum seekers and refugees. If only 12% of reception centres for asylum seekers were private in Norway in 1990, the number had risen to 77% in 2013. Nonetheless, the service providers – particularly the Norwegian group Adolfsen – were originally providing healthcare and social help and not penitentiary services. This has thus led to a more respectful treatment of the migrants.

In Australia, the migrant detention system is entirely managed by private companies which prefer a delocalised management. The Christmas Island scandal, 1.500 kilometres from the Australian shores (managed by the Transfield Services and Wilson Security contractor), has been particularly mediatised since august 2016 when a series of documents with complaints and stories of mistreatments inflicted within the centre were published in The Guardian. These documents attest to sexual violence on minors, traumas, self-mutilation and unacceptable work conditions. Following multiple investigations and parliamentary reports, the centre was shut down in 2018 but reopened in 2019, after a historic defeat of the executive, thus showing a hardening of the immigration policy, a very controversial topic in Australia[15].

In the United States, Marie Gottschalk, Professor in Political Science at Pennsylvania University, has been denouncing a “crimmigration”, i.e. the augmentation of repressive penal policies against migrants, now locked up in “retention centres”. 30 days of detention are now planned for migrants suspected of illegal immigration. CoreCivic – which got rid of the name CCA in 2016 to dissociate itself from scandals – manages more than 60 complexes in 19 States, with a 500% increase in sales in only 20 years. The company has conquered some important market shares since the SB 1070 Arizona law has been passed, a law which created a new offence: not having one’s immigration papers at all times. If the original bill first allowed police officers to arrest anyone suspicious without a warrant, the Supreme Court managed to restrict its excesses. The police can now verify someone’s ID and status if this person is committing a minor offence and if they have reasonable doubt that this person could be staying in the US illegally. This law, written by the lobby ALEC (of which CCA was an eminent member), has helped fill up detention centres. Moreover, in Arizona, CCA is in a monopolistic situation to detain migrants. A market worth approximately 11 million dollars a month.

Lobbying and mass incarceration policies

Although the fight against criminality had taken a major turn in the 1970’s with Richard Nixon, fierce advocate of a tough policy on the matter, more widely known as the Law & Order doctrine, this fight has gained intensity until the Obama years. Firstly pushed by political and electoral reasons, as the 37th president of the United States needed the traditionally democrat white population’s vote, this doctrine has slowly evolved to become a pillar of the American politico-judicial system. Ronald Reagan’s presidency (1980-1988) was the apogee of the hardening of penal policies in terms of drugs trafficking, which has largely helped the emergence of the private carceral sector to support the State. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 has notably consecrated the mandatory minimums for a large portion of the judicial system, minimums which have quickly resulted in a major augmentation of convictions, thus serving the economic interests of the emerging players. However, if Jimmy Carter’s presidency (1976-1980) had somehow halted the political trend, Bill Clinton (1992-2000) breaks the democrat/republican division by being the first democrat to be tough on crime. That transition culminates in 1994 with the Anti-Violence Strategy which aimed to fight repeated offences by enacting the Three Strikes and You’re Out rule, a rule which requires a life sentence for any third offence if one of the offences is a felony. Supported by the quickly privatising carceral system, American penal policies thus took a turn towards zero tolerance and mass incarceration.

On the other hand, to understand the impact of the American carceral privatisation phenomenon, it is crucial to understand the role played by the companies’ lobbyists to obtain a favourable legislation. To that end, the biggest player is the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a very influential conservative organisation which writes and proposes legal texts to American representatives. Indeed, this organisation puts forward more than 1.000 legislative texts a year, of which around 20% are passed into laws. Founded in 1973, this political lobbying organisation rapidly gains weight in the judicial and carceral sectors, so much so that they are behind the aforementioned Three Strikes law, as well as the mandatory minimums, but also the SB-1070, the Stand Your Ground Laws (which greatly enlarge the concept of self-defence by authorising mere suspicions as reasonable grounds) and more than 30 legislation models at both state and federal levels. Many ALEC members are personally linked to the carceral milieu, as was the case in the 1990’s when the chairman of the Criminal Justice Task Force – responsible for drafting propositions of tough penal laws – was no other than a senior executive from CCA, the largest American private prison company.

Although ALEC members regularly deny collusion allegations with the prison giants that are CCA or GEO Group, proof of such cooperation are not hard to find. A CCA shareholders’ report from 2012 actually demands to fight against tolerance and indulgence for sentences, probations and to fight against the decriminalisation of some activities. Moreover, companies like CCA pursue a very powerful and tentacular lobbyism, beyond ALEC’s scale, to directly finance numerous federal institutions such as the Justice Department, the US Marshall Service, the Bureau of Prisons, the Department for Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs or even the Senate, the Department of Labor, the Indian Affairs Bureau and the Administration for Children and Families. Lobbying spending regarding these institutions has reached 4 million dollars. However, CCA and GEO Group are also pressuring judicial policies serving their interests by directly financing political campaigns or senior members of the federal government. In 2014, CCA had financed 23 Senators and 25 Congressmen while GEO Group had paid 10 Senators and 28 Congressmen. These companies, as well as Community Education Centers, Corizon Correctional Healthcare or Global Tel Link, hire every year roughly a hundred lobbyists in several States, a certain number of them being former Congressmen. This lobbyism is not restricted to the federal scale since governors’ campaigns are also very important. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s 2003 campaign is one of many of those campaigns as the Austrian-born actor received 21.200$ so that the McFarland prison north of Los Angeles would be reopened.

Although active lobbying for laws serving their interests is obvious, ALEC, CCA and the other companies also fight for any “counter-reformation” not to be enacted and prevent any law to pass the bicameral test. This was the case for the Private Prison Information Act of 2015 which would have forced private prisons to release their records on violence in their facilities. This same year, Independent Senator Bernie Sanders’ Justice Is Not For Sale Act – which would have abolished the carceral privatisation phenomenon altogether and at every scale, so that managing justice and criminality would go back to “those who answer to voters not those who answer to investors” – suffered the lobbyists’ pressure and thus could not be enacted.

Just like ALEC, CCA and GEO Group regularly deny allegations of lobbyism and declare, for example here in 2013, that they “do not take a position on or advocate for or against any specific immigration reform legislation”. Every penny spent by these companies proves just the opposite, their economic survival largely depends upon judicial policies.

The private prison’s failures

From conviction to reinsertion, not foregoing immigration, surveillance, healthcare, consumption, labour, exploitation, the private carceral system uses justice and safety concepts to develop an inhuman economic model with people as its first commodity. Tied to political, ideological considerations, to lobbies and corporations’ financial interests, this system has replaced prisoners’ rehabilitation with for-profit policies and mass incarceration. On top of ethical considerations, the private prison system constantly shows its failures compared to the public management seeing how poor its results are. The amount of violence (between inmates as well as between inmates and guards) is 1 to 2 times superior in private prisons, inmate complaints are not directed towards disciplinary procedures or trial issues but towards access to healthcare and guard violence, families take on massive debts just to keep a connection with an inmate that most likely did not get a fair trial. If the loopholes in the 13th Amendment are not of the private prisons’ making, they are ruthlessly exploited, thus turning the constitutional rights so dear to the Americans into ridicule.

The imposition of the carceral privatisation phenomenon in the American landscape – but also internationally – has perverted an entire equilibrium of society which theoretically means to reduce criminality rates. At this game, prison turns out to be ineffective and inefficient. Although some news outlets revel in macabre minor news items to justify violent carceral repression policies, recidivism rates, Richter’s scale of the prison system’s efficacy, should convince politicians to change their rhetorics. In France, 63% of offenders are convicted a second time. The private prison’s failures bring us to question the role of the State in rehabilitating and reinserting its convicted citizens, and more broadly to interrogate the prison’s very functioning.

However, such a change is not in the foreseeable future for most of countries we have mentioned so far. Indeed, between 1987 and 2007, the United States have increased their prison spending by 127% while education spending had only increased by 21%. Victor Hugo’s recommendation, “open up schools, you will shut prisons down”, is getting further and further away.

Arthur Deveaux–Moncel & Florian Mattern

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

- Mason, Cody “Dollars and Detainees: the Growth of For-Profit Detention”, The Sentencing Project (2012), pp. 1-21.

- Isaacs, Caroline “Community Cages: Profitizing community corrections and alternatives to incarceration”, American Friends Service Committee (2016), pp. 1-32.

- Mason, Cody “International Growth Trends in Prison Privatization”, The Sentencing Project (2013), pp. 1-18.

- “Buying Influence: How Private Prison Companies Expand their Control of America’s Criminal Justice System” In the Public Interest (2016), pp. 1-18.

- Dippel, Christian & Poyker, Michael “Do Private Prisons Affect Criminal Sentencing?”, NBER Working Paper N°25715 (2020)

- Harcourt, Bernard The illusion of free markets : punishment and the myth of natural order, (2011)

- Review of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Monitoring of Contract Prisons, Office of the Inspector General, U.S. Department of Justice (2016), pp. 1-80.

- Justice is Not For Sale Act of 2015, introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders on September 17th, 2015, pp. 1-64.

- “The Prison Industrial Complex: Mapping Private Sector Players”, Worth Rises (2019), pp. 1-14.

- Isaacs, Caroline “Treatment Industrial Complex: How For-Profit Prison Corporations are Undermining Efforts to Treat and Rehabilitate Prisoners for Corporate Gain”, American Friends Service Committee (2014), pp. 1-20.

- Mason, Cody “Too Good to Be True: Private Prisons in America”, The Sentencing Project (2012), pp. 1-22.

- Monique Seyler, De la prison semi-privée à la prison vraiment publique. La fin du système de l’entreprise générale sous la IIIe République, 1989.

- Foucault, Michel Surveiller et punir, (Gallimard, Paris : 2019)

- Lethbridge, Jane “Privatisation des services aux migrants et aux réfugiés et autres formes de désengagement de l’État”, (2017), Public Services International & European Public Service Union.

- Liaras, Barbara “États-Unis: à qui profite la prison ?”, 2011, Observatoire International des Prisons

- Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO)

[1] J. Hanway, The Defects of Police (1775)

[2] Ch. Chabroud Archives parlementaires, t. XXVI p.618

[3] Cody Mason, “International growth trends in prison privatization”

[4] Migreurop, La détention des migrants dans l’Union européenne : un business florissant, July 2016

[5] “Prison Labor”, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO, August 5th, 2019)

[6] The 13th, documentary directed by Ava DuVernay in 2016

[7] “Prison Labor”, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO, August 5th, 2019)

[8] Washington Post, Yes, prisoners used to sew lingerie for Victoria’s Secret — just like in ‘Orange is the New Black’ Season 3

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/fashion/prison-labor-fashion-brands.html

[10]https://www.rfi.fr/fr/ameriques/20180909-greve-prisonniers-etats-unis-travail-conditions-salaires

[11] Probation is a court procedure that allows convicted offenders to avoid serving all or part of their sentences in jail. Parole is only granted after offenders have served some of their time, amounting to an early release.

[12] Erving Goffman, Stigmates, (1963)

[13] Word used in 2011 by Gerry Gaes, former Research Director at the Federal Bureau of Prisons

[14] Louise Tassin “Quand une association gère un centre de rétention, le cas de Lampedusa (Italie)”, Ve Congrès de l’association française de sociologie 04/09/2014

[15] https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2019/02/13/canberra-rouvre-le-centre-de-detention-de-refugies-de-l-ile-christmas_5422683_3210.html

No Comment